Monetary policy assessment

Consumer prices have risen rapidly, and inflation is markedly above target. Activity in the Norwegian economy is still high, and unemployment has remained very low. At the same time, the Norwegian economy is slowing down.

Since the September 2022 Monetary Policy Report, inflation has been higher than projected and is expected to remain high for longer than previously projected. At the same time, the labour market appears to be a little tighter than anticipated. On the other hand, the policy rate has been raised considerably over a short period of time, and monetary policy has started to have a tightening effect on the economy. There are signs that the slowdown may prove somewhat more pronounced than envisaged in September.

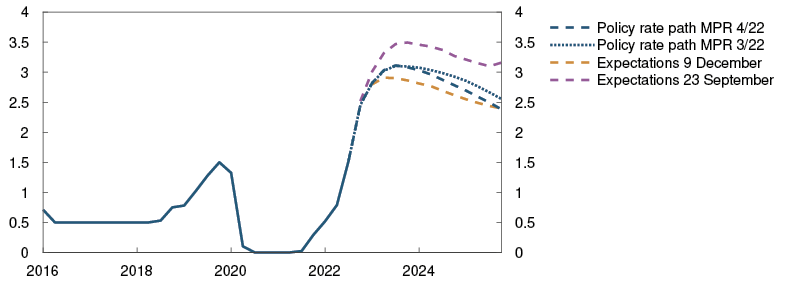

Norges Bank’s Monetary Policy and Financial Stability Committee decided to raise the policy rate from 2.5% to 2.75% at its meeting on 14 December. Based on the Committee’s current assessment of the outlook and balance of risks, the policy rate will most likely be raised further in 2023 Q1.

High inflation and weaker global growth outlook

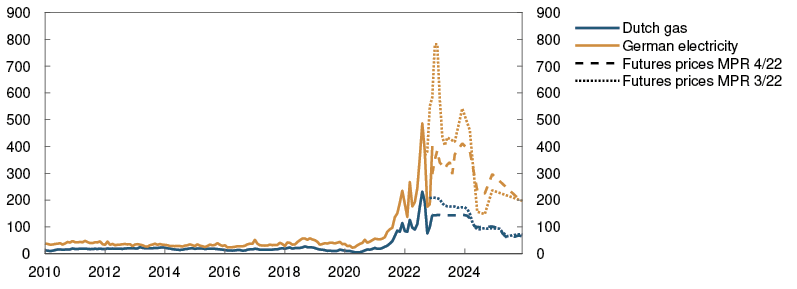

Elevated energy prices, strong demand and supply side constraints have led to high global inflation over the past year, but consumer price inflation may now have passed the peak in some countries, such as the US. Futures prices indicate that both gas and electricity prices will remain high over the coming year but will fall thereafter. Other commodity prices have edged down over the past six months, and global supply chain disruptions appear to have eased. Global freight rates have shown a marked decline.

Chart A Lower gas and electricity prices1 Øre/kWh

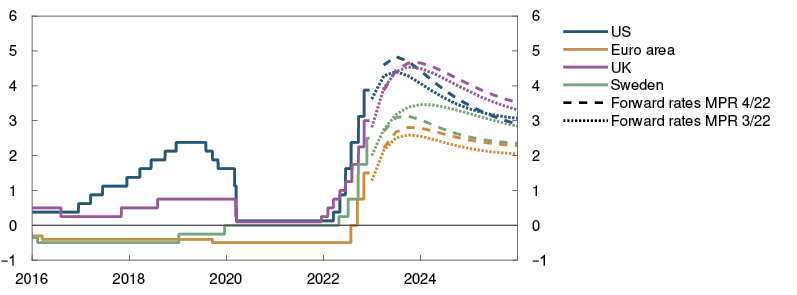

Central banks in many trading partner countries have responded to the surge in inflation by raising policy rates to the highest levels seen in more than a decade. Labour markets are tight, but the fall in unemployment appears to have come to a halt in some countries. Wage growth has accelerated and is expected to remain high next year. Economic activity among our trading partners has been slightly higher than projected in the September Report, but forward-looking indicators point to weaker growth ahead. High inflation and higher interest rates are expected to curb consumption growth. At the same time, high energy prices have prompted some European companies to scale back production. GDP growth among our trading partners is expected to be low next year.

Chart B Sharp tightening of monetary policy in many countries2 Policy rates and estimated forward rates in selected countries. Percent

Volatile financial markets

Financial markets have been highly volatile since the September Report. Market-based expectations of global policy rates are a little higher in the near term but indicate expectations of a gradual moderation in the pace of policy rate hikes over the next year.

The krone exchange rate has fluctuated considerably in recent months but is now broadly in line with the projections in the September Report. The volatility in financial markets is adding to the uncertainty about movements in the krone exchange rate ahead. The expected path of Norway’s policy rate has fallen since September. Higher money market premiums have pushed up corporate borrowing costs. The rise in mortgage lending rates has been broadly as expected.

High activity in the Norwegian economy, but prospects for weaker growth ahead

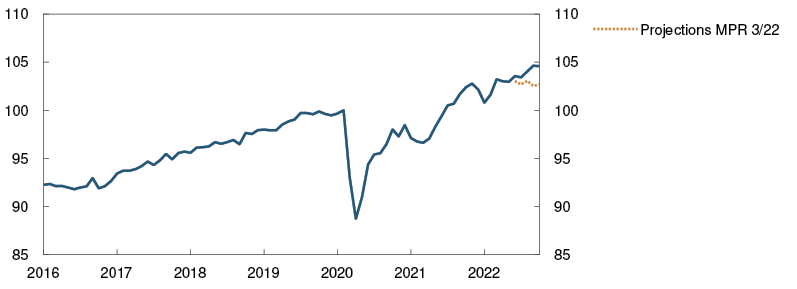

Activity in the Norwegian economy has been higher through 2022 than previously assumed, and mainland GDP has increased faster in recent months than expected. High inflation and higher interest rates have reduced household purchasing power, but consumption has so far remained higher than projected in the September Report.

Chart C Higher-than-projected economic activity3 GDP for mainland Norway. Seasonally adjusted. Index. February 2020 = 100

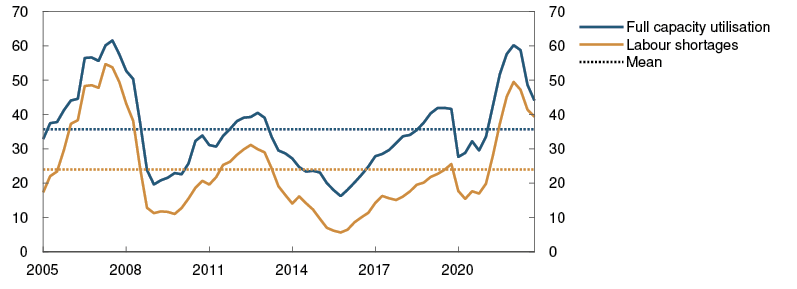

The labour market is tight. Employment has continued to rise, and unemployment has remained very low. Seasonally adjusted registered unemployment was 1.6% in November, which was slightly lower than projected in the September Report. There are still considerable labour shortages, but shortages are easing. The share of enterprises in Norges Bank’s Regional Network reporting that labour shortages are limiting output fell further in November. The number of job vacancies has also decreased.

Chart D Labour shortages have eased4 Capacity utilisation and labour shortages according to the Regional Network. Percentage shares

Regional Network enterprises on the whole expect a marked decline in output over the next half year. Enterprises expect lower demand ahead, on the back of high price and cost inflation, higher interest rates and a decline in public sector projects.

The housing market has turned. House prices have fallen faster than projected, and the number of unsold homes has increased markedly. House prices are expected to fall further in the period to autumn 2023. A reduction in household wealth due to a fall in house prices, combined with the prospect of a notable decline in household real disposable income in 2023, pushes down consumption between 2022 and 2023. The household saving ratio is declining, and saving is expected to remain low ahead.

Activity in the Norwegian economy is projected to fall in the near term. Higher inflation and a weaker housing market are expected to contribute to a more rapid cooling of the Norwegian economy than envisaged in September. Substantial investments in the petroleum industry and activities related to climate transition are expected to lift activity somewhat further ahead.

Prospects of high inflation for a longer period

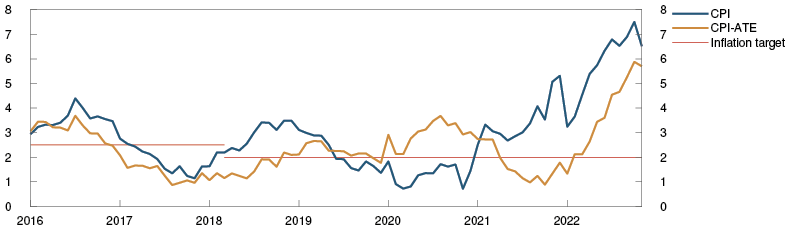

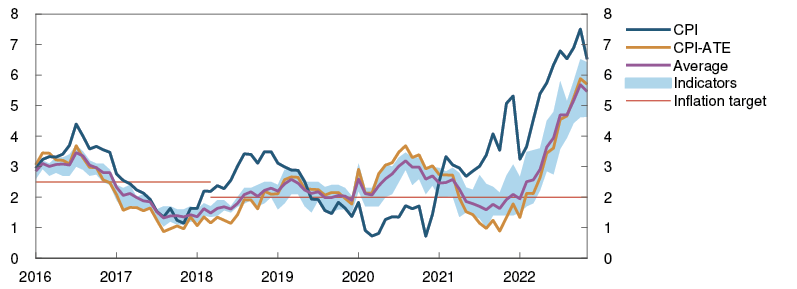

Inflation in Norway is high and appreciably higher than projected in the September Report. In November, the 12-month rise in the consumer price index (CPI) was 6.5%. Energy and food prices in particular have risen sharply over the past year, but prices across a range of other goods and services have also risen more than normal. The 12-month rise in the consumer price index adjusted for tax changes and excluding energy products (CPI-ATE) has moved up and stood at 5.7% in November. Prices for both imported goods and domestically produced goods and services are rising at a fast pace. Other indicators of underlying inflation have also edged higher. Inflation is expected to remain higher in the period ahead than previously projected.

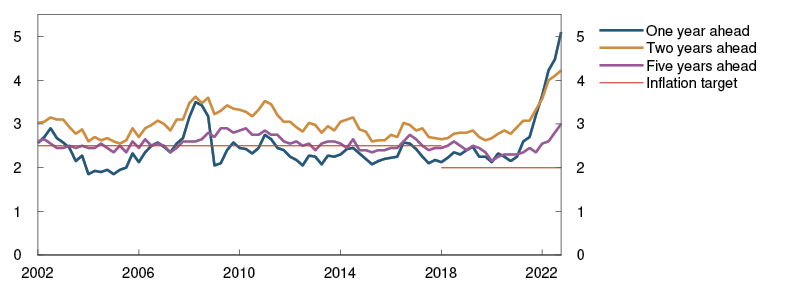

According to Norges Bank’s Expectations Survey, inflation expectations for the coming years have increased recently. Long-term inflation expectations increased further in 2022 Q4 and are above the 2% target.

Wage growth is set to be higher in 2022 than in 2021, partly reflecting labour market tightness. Register-based wage statistics indicate that wage growth in the first three quarters of 2022 may have been slightly lower than projected. The projection for wage growth in 2022 has been revised down to 3.9%, implying a sharp decline in real wages. Norges Bank’s Expectations Survey indicates that wage growth expectations for 2023 have increased since September and nominal wage growth is expected to show a marked increase in 2023.

Chart E Inflation markedly above the 2% target5 CPI and CPI-ATE. Twelve-month change. Percent

Need for higher interest rates in the Norwegian economy

The operational target of monetary policy is annual consumer price inflation of close to 2% over time. Inflation targeting shall be forward-looking and flexible so that it can contribute to high and stable output and employment and to countering the build-up of financial imbalances.

The Committee assesses that a higher policy rate is still needed to dampen inflation. Consumer prices have risen rapidly, and inflation is markedly above target. Activity in the Norwegian economy is still high, and unemployment has remained very low. At the same time, the economy is slowing down, and higher inflation is reducing household purchasing power. An easing of economic pressures will help curb inflation further out.

Since the September Report, inflation has been higher than projected and is expected to remain high for longer than previously projected. At the same time, the labour market appears to be a little tighter than anticipated. On the other hand, the policy rate has been raised considerably over a short period of time, and monetary policy has started to have a tightening effect on the economy. There are signs that the slowdown may prove somewhat more pronounced than envisaged in September.

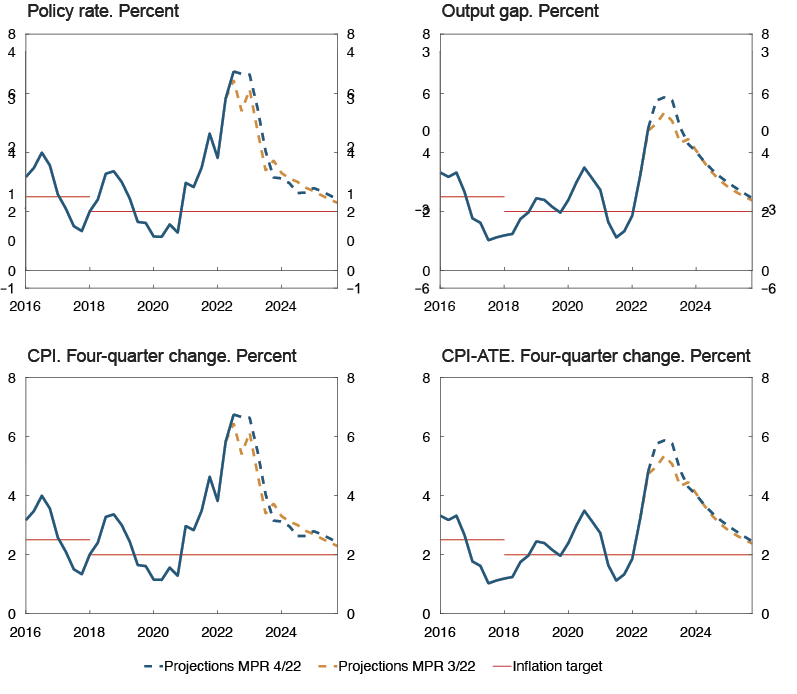

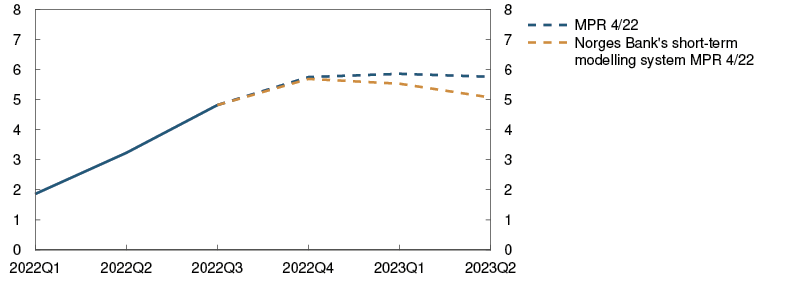

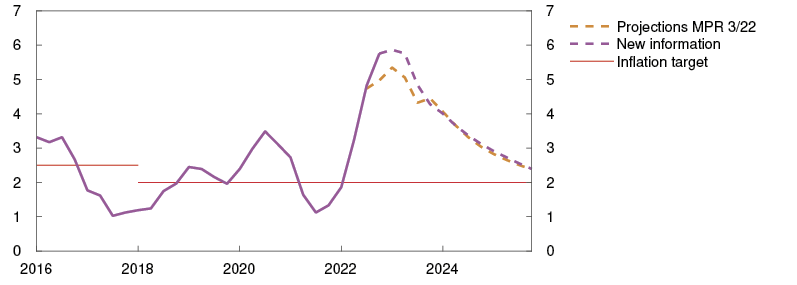

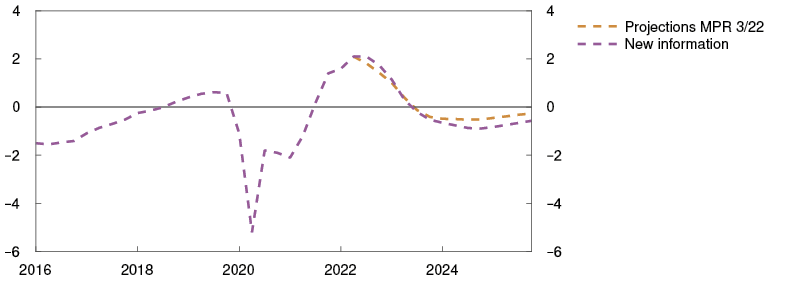

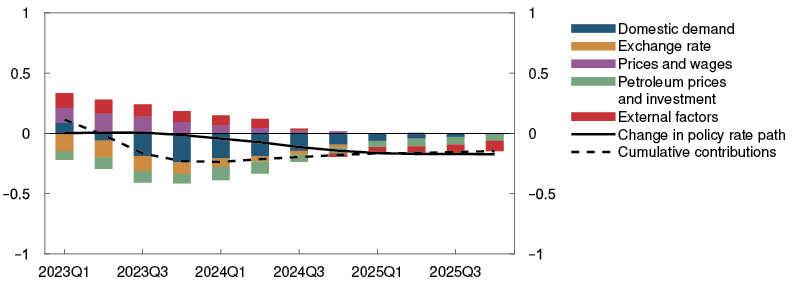

Chart F Higher policy rate curbs inflation6

The policy rate forecast indicates a policy rate of around 3% in 2023, slightly higher than in the previous Report. In the projections, inflation falls and approaches the inflation target further out. The output gap falls, and output stays somewhat below potential in the coming years. Unemployment then increases somewhat, albeit from a low level.

In its discussion, the Committee was concerned with higher-than-normal uncertainty surrounding the forecasts for the Norwegian economy. There is uncertainty associated with households’ response to higher inflation and increased interest rates, and the potential effects of high inflation on wage and price formation. The future path of the policy rate will depend on economic developments. If the pressures in the economy persist, and signs emerge that inflation will remain high for longer than currently projected, a higher policy rate may be needed than currently envisaged. If inflation falls faster or unemployment rises more than projected, the policy rate may be lower than projected.

The Committee decided unanimously to raise the policy rate by 0.25 percentage point to 2.75%. Based on the Committee’s current assessment of the outlook and balance of risks, the policy rate will most likely be raised further in 2023 Q1.

Ida Wolden Bache

Pål Longva

Øystein Børsum

Ingvild Almås

Jeanette Fjære-Lindkjenn

14 December 2022

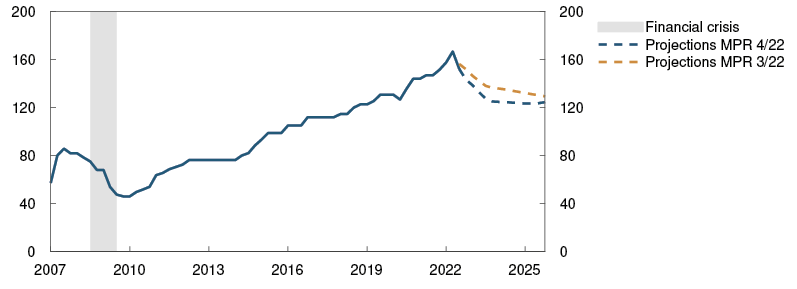

1 Period: January 2010 – December 2025. Futures prices at 20 September 2022 for MPR 3/22 and at 13 December 2022 for MPR 4/22.

2 Period: 1 January 2016 – 31 December 2025. Daily data through 13 December 2022. Quarterly data from 2022 Q4 for MPR 3/22 and 2023 Q1 for MPR 4/22. Forward rates at 16 September 2022 for MPR 3/22 and at 13 December 2022 for MPR 4/22. ECB’s deposit facility rate for the euro area.

3 Period: January 2016 – October 2022. Projections from June 2022 for MPR 3/22.

4 Period: 2005 Q1 – 2022 Q4. Share of contacts that will face some or considerable difficulty meeting increased demand and share of contacts citing labour shortages as a constraint on production. The question about labour is asked only of the enterprises reporting full capacity utilisation, but the series shows the share of all contacts included in the interview period. The local government and hospital sector is omitted from the capacity utilisation series, but is, however, included in the labour force series.

5 Period: January 2016 – November 2022. CPI-ATE: CPI adjusted for tax changes and excluding energy products.

6 Period: 2016 Q1 – 2025 Q4. Projections from 2022 Q3 for MPR 3/22 and 2022 Q4 for MPR 4/22 for the policy rate, CPI and CPI-ATE. The output gap measures the percentage deviation between mainland GDP and estimated potential mainland GDP. CPI-ATE: CPI adjusted for tax changes and excluding energy products.

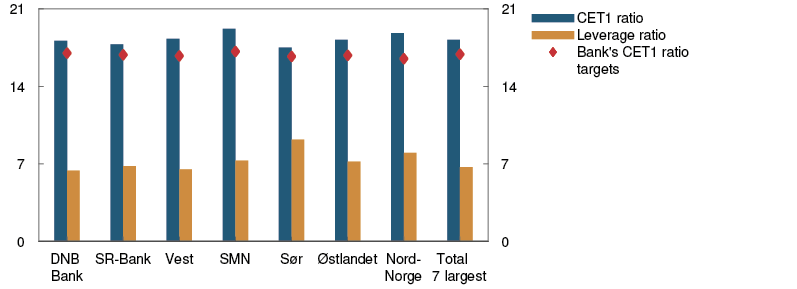

Assessment of the countercyclical capital buffer requirement

In March, the decision was made to raise the countercyclical capital buffer rate to 2.5%, effective from 31 March 2023. At its meeting on 14 December, Norges Bank’s Monetary Policy and Financial Stability Committee decided to maintain this requirement.

The countercyclical capital buffer is intended to strengthen banks’ solvency and mitigate the risk that banks amplify an economic downturn. If a downturn will or could cause a marked reduction in credit supply, the countercyclical capital buffer rate should be lowered.

Activity in the Norwegian economy is still high, and unemployment has remained very low. At the same time, the Norwegian economy is slowing down. The uncertainty surrounding the forecasts for the Norwegian economy is higher than normal.

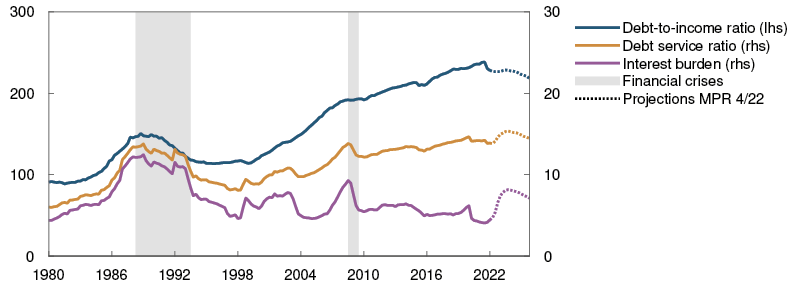

Property prices have risen substantially in recent years, and many households are highly indebted. Such vulnerabilities may amplify a downturn. Household credit growth has slowed in autumn, while corporate credit growth has remained elevated. At the same time, residential and commercial property prices have fallen, and they are expected to fall further. Persistently low yields increase the risk of a sharp fall in commercial property prices.

Creditworthy firms and households appear to have ample access to credit, even if there are some signs of a tightening of banks’ credit standards. Bond risk premiums have risen markedly in 2022, particularly for commercial real estate firms.

Norwegian banks satisfy the capital requirements and are highly profitable. Bank losses are expected to be low ahead. Analyses in Financial Stability Report 2022 show that banks are resilient and able to absorb losses and maintain lending in a severe economic downturn. The countercyclical capital buffer rate of 2.5% helps banks to remain resilient so that they can perform their tasks also in the event of economic downturns.

The Committee unanimously decided to keep the countercyclical capital buffer rate at 2.5%.

Ida Wolden Bache

Pål Longva

Øystein Børsum

Ingvild Almås

Jeanette Fjære-Lindkjenn

14 December 2022

1 The global economy

Consumer price inflation is very high in many countries. European gas and electricity prices remain at high levels, but futures prices for the coming year are lower than in September. The high level of inflation is reducing household purchasing power. Trading partner GDP growth is expected to be low in 2023. The projection has been revised down since the September 2022 Monetary Policy Report. The high degree of financial market volatility has persisted since September. Market forward rates indicate that policy rate expectations for the period ahead are slightly higher than in September and that central banks will gradually slow the pace of monetary policy tightening.

High gas and electricity prices dampen activity ahead

Among most of Norway’s trading partners, labour markets are tight, and GDP rose more than expected between 2022 Q2 and Q3. Growth picked up in the US and China, while activity levels in the euro area and the UK were little changed.

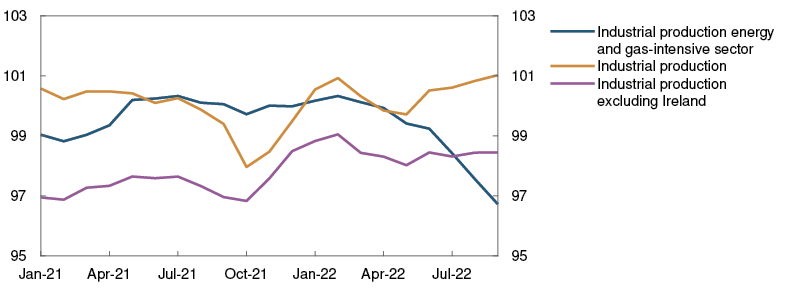

Growth prospects for the coming quarters are weak. European gas and electricity prices remain at historically high levels. Futures prices indicate that gas and electricity prices will remain elevated but in the coming year, be lower than assumed in the September Report (see "Futures prices for energy and other commodities remain high"). In autumn, many European firms scaled back production due to high energy costs (Chart 1.1). Households in many countries are receiving fiscal support, but energy costs will still be high in the coming quarters. It is difficult to project the economic impact of gas and electricity market developments. High gas and electricity prices are now expected to dampen activity in Europe more than assumed in the September Report.

Chart 1.1 Energy-intensive industrial production in the euro area has fallen1 Industrial production. Index. 2019 = 100. Three-month moving average

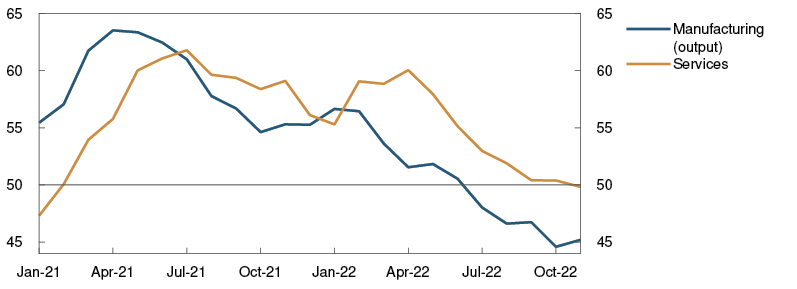

Consumer price inflation is very high. In addition, many central banks have raised their policy rates substantially since spring, and market policy rate expectations indicate further rate hikes in the period to summer 2023 in both Europe and the US. Households are expected to reduce saving further, but consumption in Europe will likely decline in the coming quarters due to the high cost of living. Activity indicators for manufacturing and services are low (Chart 1.2), and investment is expected to decline ahead. These factors combined imply a likely decline in European economic activity through autumn and winter. In addition, lockdowns related to higher Covid infection rates will dampen growth in China.

Chart 1.2 Activity indicators point to lower growth in Europe2 PMI manufacturing (output) and services

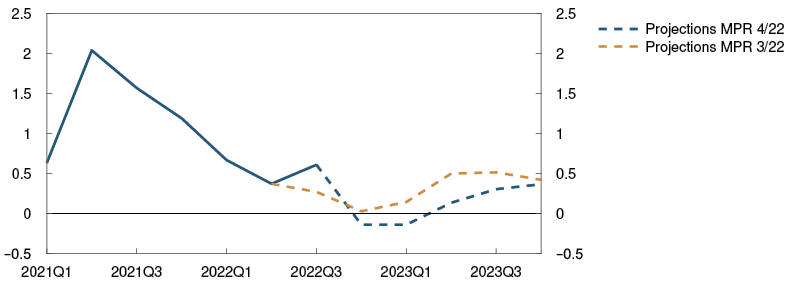

Monetary policy is assumed to be tightened in line with market policy rate expectations and commodity prices to move in line with futures prices. In the UK, there are plans for considerable fiscal tightening, while higher defence and energy investment in Europe are likely to boost activity further out in the projection period. In China, growth is expected to be slower ahead than in the pre-pandemic years. This partly reflects measures to ensure more domestic consumption-driven growth and less dependence on foreign trade, as well as ongoing trade conflicts with other countries. Trading partner GDP growth is projected to slow from 3.4% in 2022 to 0.5% in 2023, before picking up again in 2024 (Annex Table 1). The projections for 2023 and 2024 have been revised down since the September Report (Chart 1.3). Import growth among trading partners is projected to fall from over 7% in 2022 to below zero in 2023.

Chart 1.3 Weaker growth outlook3 GDP for trading partners. Quarterly change. Seasonally adjusted. Percent

High consumer price inflation

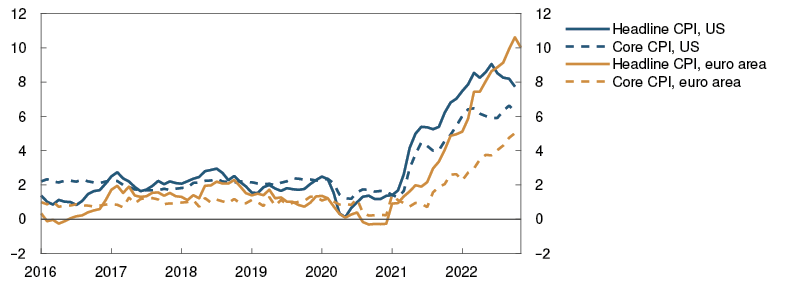

Pandemic-related supply and demand conditions and the war in Ukraine have contributed to high inflation among Norway’s main trading partners since autumn 2021, but consumer price inflation may now have passed the peak in some countries, such as the US. In the US, 12-month CPI inflation fell somewhat in recent months, while core CPI inflation has run slightly above 6% (Chart 1.4). In the euro area, headline inflation slowed to 10% from October to November 2022. Both energy and food price inflation is high. Underlying consumer price inflation was 5% in November. In recent months, underlying inflation among trading partners has been higher than projected in the September Report, particularly in Europe.

Chart 1.4 Consumer price inflation remains high4 Consumer prices. Twelve-month change. Percent

Goods freight rates have fallen substantially over the past six months, with rates from Asia to the US down to pre-pandemic levels. At the same time, many commodity prices fell markedly over summer and autumn, which will eventually dampen consumer goods inflation. On the other hand, high energy prices have pushed up business costs, with some expected pass-through to prices for goods and services.

Labour markets are tight, but the fall in unemployment appears to have come to a halt in a number of countries and labour demand appears to be declining in both the US and Europe. Wage growth among Norway’s main trading partners is projected to be about 4.5% in both 2022 and 2023, slowing gradually thereafter. Long-term market-based inflation expectations are little changed since the September Report and are close to the inflation targets of both the US and the euro area. Underlying consumer price inflation for trading partners as a whole is projected to slow from 4.8% in 2022 to slightly above 4% in 2023, before gradually drifting down to around 2%. The projections have been revised up from the September Report.

Further policy rate rises abroad

Since the September Report, central banks abroad have continued to tighten monetary policy, primarily in response to high inflation. Central banks in the US, euro area, UK and Sweden have all raised their policy rates, which are now at their highest levels since the financial crisis. The market’s policy rate expectations for the coming period have risen slightly since the September Report. At the same time, forward rates indicate expectations of a slower pace of increase in policy rates in the coming year, which also reflects what most central banks have signalled.

The high degree of financial market volatility has persisted. Long-term global government bond yields rose in autumn but fell back in recent weeks to approximately the same level as in the September Report (Chart 1.5). Global equity indexes have advanced slightly since the September Report, while corporate bond risk premiums have declined.

Chart 1.5 Volatility in long-term interest rates5 Ten-year government bond yields for selected countries. Percent

Uncertainty surrounding the economic outlook

The ongoing war in Ukraine is adding to the uncertainty about developments ahead. The effects of the current broad and simultaneous monetary policy tightening are also uncertain. There is a risk that the higher cost of living for households and higher business costs will lead to lower consumption and investment among trading partners than currently envisaged. Consumer price inflation may then fall more rapidly. Energy supply constraints may also dampen activity more than anticipated. On the other hand, growth may prove to be stronger than expected if households spend more of their savings. The projections assume that wage earners will not be fully compensated for the high rate of inflation, but if that were to be the case, price and wage inflation could remain high for longer than currently expected. The pandemic is still adding to uncertainty. In China, the easing of pandemic-related restrictions may lift activity more than expected in the near term but could also lead to more lockdowns further ahead. There is also a risk of further decline in the Chinese housing market.

1 Period: January 2021 – September 2022. Energy- and gas-intensive sectors comprise mining and quarrying, manufacture of basic metals and fabricated metal products, except machinery and equipment, manufacture of rubber, plastic products and other non-metallic mineral products, manufacture of wood, paper, printing and reproduction of recorded media, manufacture of chemicals and chemical products and manufacture of coke and refined petroleum products. Weighted by share of total industry added value in 2019.

2 Period: January 2021 – November 2022. Aggregate for the euro area, UK and Sweden. Export weights.

3 Period: 2021 Q1 – 2023 Q4. Projections from 2022 Q3 for MPR 3/22 and from 2022 Q4 for MPR 4/22. Export weights. 13 trading partners.

4 Period: January 2016 – November 2022. Core CPI is consumer prices excluding energy and food in the US and consumer prices excluding energy, food, tobacco and alcohol in the euro area. Data to October for the US and to November for the euro area.

5 Period: 1 January 2020 – 9 December 2022.

Futures prices for energy and other commodities remain high

Energy and non-energy commodity prices are set to remain elevated ahead but have fallen back from the record levels seen earlier in 2022.

Key energy prices on the continent, such as Dutch wholesale gas and German wholesale electricity prices, are lower for this year and 2023 than envisaged in September (see Chart A in “Monetary policy assessment”), reflecting different EU policy measures for energy saving, higher energy production, and signals of possible price regulation. Moreover, energy consumption has declined as a result of mild weather through autumn. In addition, wind power production was high and the supply of liquified natural gas (LNG) was ample. European gas inventories increased and fears of winter rationing have eased. In recent weeks, wholesale natural gas and electricity prices have increased again, in large part due to cold, still and dry weather.

European futures prices indicate that wholesale gas and electricity prices will remain high in the year ahead. Uncertainty about price developments is very high, particularly related to the level of Russian gas exports and French nuclear power production. In addition, winter weather plays a significant role. Further ahead, futures contracts suggest that prices will again decline, although prices are expected to remain higher than they have been historically (Table 1.A). A prolonged reduction in Russian gas exports and problems related to nuclear power production in France could contribute to energy shortages in Europe in the coming years.

Table 1.A Energy and commodity prices

|

Percentage change from projections in Monetary Policy Report 3/22 in brackets |

Average price |

Actual prices and futures prices1 |

|||||

|

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

2025 |

||

|

Oil, USD/barrel |

80 |

42 |

71 |

101 (-1) |

77 (-8) |

75 (-4) |

73 (-2) |

|

Gas, USD/barrel |

40 |

18 |

87 |

207 (-16) |

235 (-18) |

180 (2) |

120 (0) |

|

Petroleum2, USD/barrel |

63 |

34 |

85 |

164 (-16) |

200 (-18) |

153 (1) |

106 (-1) |

|

Coal, EUR/tonne |

66 |

44 |

102 |

278 (-5) |

241 (-17) |

234 (-14) |

213 (-18) |

|

Emission allowance prices, EUR/tonne |

10 |

25 |

53 |

81 (1) |

89 (19) |

94 (19) |

99 (18) |

|

German electricity, Øre/kWh |

36 |

36 |

106 |

265 (-20) |

392 (-25) |

297 (19) |

192 (-3) |

|

Nordic electricity, Øre/kWh |

32 |

12 |

64 |

148 (-16) |

209 (20) |

99 (25) |

79 (24) |

|

Electricity in southern Norway, Øre/kWh |

31 |

10 |

78 |

205 (-26) |

254 (-3) |

135 (11) |

107 (13) |

|

Electricity in northern Norway, Øre/kWh |

32 |

10 |

40 |

32 (23) |

50 (35) |

50 (47) |

49 (58) |

|

Aluminium, in thousands of USD/tonne |

1.9 |

1.7 |

2.5 |

2.7 (1) |

2.5 (8) |

2.6 (7) |

2.7 (6) |

|

Copper, in thousands of |

6.8 |

6.2 |

9.3 |

8.8 (1) |

8.5 (11) |

8.5 (11) |

8.5 (11) |

|

Wheat, USD/tonne |

210 |

202 |

258 |

331 (-2) |

276 (-15) |

280 (-10) |

268 (-6) |

|

Maize, USD/tonne |

183 |

143 |

227 |

271 (-1) |

246 (-5) |

231 (-3) |

214 (-1) |

1 Futures prices at 9 December 2022.

2 An estimated Norwegian petroleum export price. The price has been estimated based on the share of oil and gas in historical export figures. For futures prices, oil and gas have equal shares.

Sources: Refinitiv Datastream and Norges Bank

Wholesale electricity prices in southern Norway are also lower than assumed in the September Report, reflecting developments in European wholesale gas and electricity prices and higher water reservoir levels (Chart 1.A). Electricity futures prices for southern Norway are also lower than in September, but cold, still and dry weather has led to increased prices here as well in recent weeks. Futures prices indicate that wholesale electricity prices are expected to be markedly higher in the coming years than they have been historically. In northern Norway, wholesale electricity prices have recently increased substantially, primarily owing to lower wind and nuclear power production in Sweden and Finland. Futures prices nonetheless indicate that prices in northern Norway will remain lower than in southern Norway.

Chart 1.A Lower electricity prices in southern Norway but higher prices in Northern Norway1 Øre/kWh

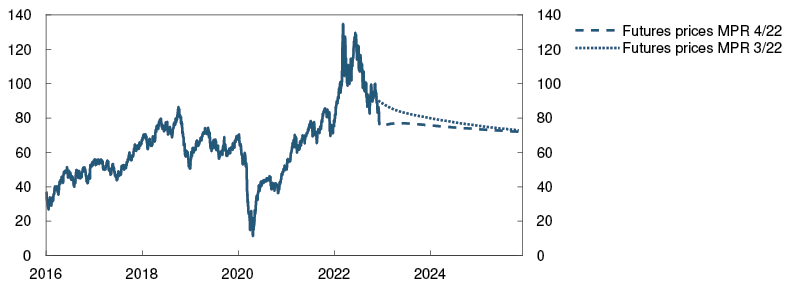

Oil prices have declined since September and are around USD 75 per barrel (Chart 1.B). Futures prices further ahead have changed less and indicate a decline in oil prices to approximately USD 70 per barrel in 2025 (Table 1.A). Oil prices may fall more if global economic growth slows further. On the other hand, oil prices may remain elevated if OPEC+ cuts oil production further. In addition, the impact of the EU’s ban on Russian oil imports on Russian oil exports and the G7’s price cap on the sale of Russian oil to other countries is highly uncertain.

Chart 1.B Lower oil prices2 USD/barrel

Industrial metals prices have risen since the September Report. An increased need for metals for the energy transition pushes up metals demand, while higher energy costs and other production factors are limiting supply. Futures prices have shown little change compared with the September Report and indicate that prices in the coming years will be higher than pre-pandemic levels (Table 1.A).

Overall, prices for global agricultural products and fertilisers are somewhat lower than in September, albeit still significantly higher than before the pandemic. More droughts and floods, geopolitical uncertainty and higher intermediate goods prices are also contributing to high futures prices for agricultural products, but these have declined somewhat since the September Report.

2 Financial conditions

Financial conditions in Norway are slightly tighter now than at the time of the September 2022 Monetary Policy Report. A higher policy rate has contributed to a further rise in interest rates on residential mortgage loans and corporate financing. Higher money market premiums have led to a further rise in corporate lending rates. The exchange rate has fluctuated considerably but is now close to the levels in September.

2.1 Monetary policy since September

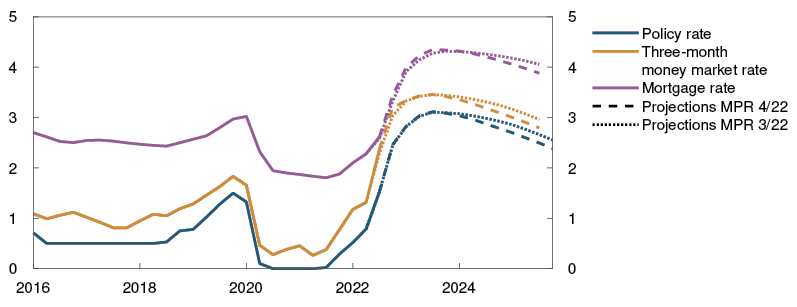

At the monetary policy meeting on 21 September, the decision was made to raise the policy rate from 1.75% to 2.25%. The projections in the September Report were based on a rise in the policy rate to around 3% in the course of winter. At the monetary policy meeting on 2 November, the policy rate was raised further to 2.50%.

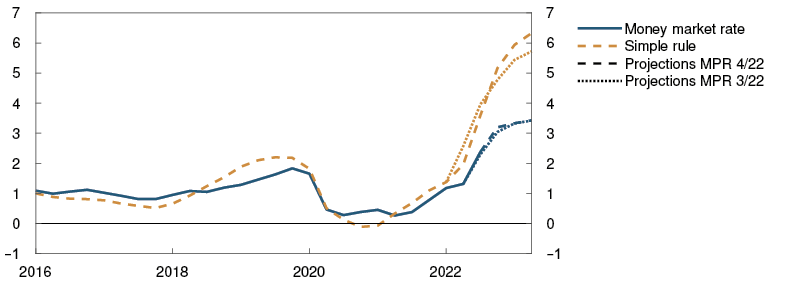

The market had priced in some probability of a larger rate hike in November. Market-based policy rate expectations have fallen since the publication of the September Report and are lower than the policy rate forecast in this Report.

Norges Bank has constructed a financial conditions index (FCI) that looks at financial conditions beyond the policy rate (see "A financial conditions index (FCI) for Norway"). The FCI shows that these financial conditions tightened through autumn but are now close to the levels prevailing in September.

2.2 Household and corporate lending rates

Higher residential mortgage rates ahead

Household interest payments have risen in pace with the rise in the policy rate. At the end of October, the average interest rate on outstanding mortgages was 3.3%, nearly 1 percentage point higher than at the beginning of July, broadly in line with that projected.

Around 85% of the policy rate increase since autumn 2021 has so far passed through to residential mortgage rates. The pass-through from the policy rate to deposit rates has been substantially lower than to lending rates but has recently risen a little. The average household deposit rate was 1.1% at the end of October. The lower pass-through to deposit rates has enabled banks to maintain underlying profitability without raising residential mortgage rates by as much as the policy rate.

In the projections, residential mortgage rates continue to increase in response to further increases in the policy rate, but still somewhat less than the rise in the policy rate. The forecast implies a rise in the average residential mortgage rate to around 4.3% in the course of 2023 (Chart 2.1).

Chart 2.1 Residential mortgage rates have risen1 Interest rates. Percent

Higher interest costs for new corporate funding

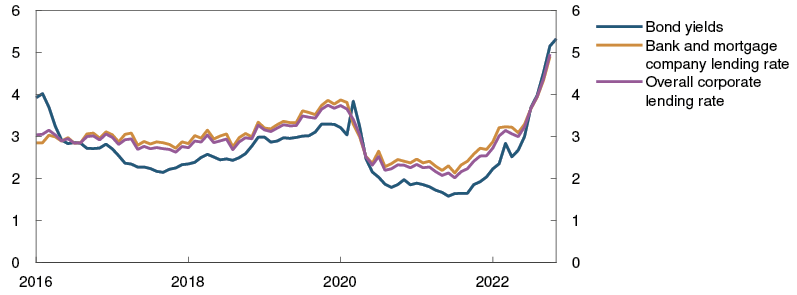

Mainland firms’ interest-bearing NOK-denominated debt primarily comprises bank loans and debt securities. Over the past year, new corporate bank and bond funding has become gradually more expensive.

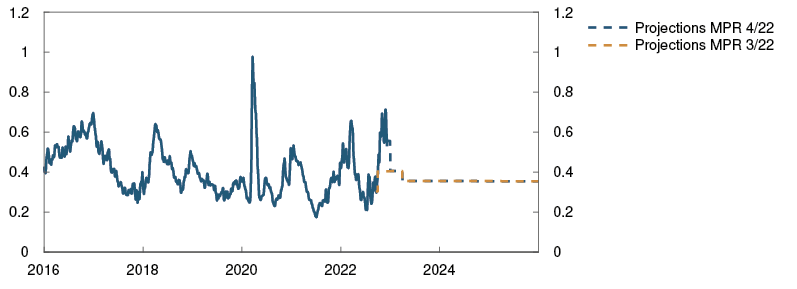

Floating-rate corporate funding, both bank and market funding, is closely linked to three-month Nibor. The increase in interest rates over the past year primarily reflects a higher policy rate and expectations of further policy rate increases (Chart 2.2). Since September, the Nibor premium has been higher than anticipated in the September Report, mainly owing to higher prices for US money market funding and low structural liquidity in the Norwegian banking system. So far in 2022 Q4, the premium has stood at just below 0.6 percentage point (Chart 2.3). The premium is expected to drift down towards 0.35 percentage point through winter. The projections are close to the market’s pricing of the forward Nibor premium.

Chart 2.2 Higher corporate lending rates2 Interest rates on new floating-rate NOK funding for mainland non-financial enterprises. Percent

Chart 2.3 Money market premium has been higher than projected3 Money market premium. Percentage points

In addition to the money market rate, firms pay a premium on new funding in the form of a margin on bank funding and a risk premium in the bond market. Because total bank debt outstanding is around three times larger than bond debt, firms will be particularly affected by changes in bank lending spreads. Historically, the risk premium in the securities market has been quite volatile, while bank lending spreads on new loans have been relatively stable over a longer period.

Recently, bank lending spreads, as reflected in Statistics Norway’s interest rate statistics, have declined a little. However, a number of surveys, such as Norges Bank’s lending survey for Q3, may indicate that the lending spread will edge up from the current level. The risk premiums on new bond market financing have risen markedly over the past year and continued to rise into Q4. In recent weeks, risk premiums overall fell back to the levels in September. For commercial real estate companies, risk premiums have continued to rise.

A number of firms pay fixed rates on portions of their debt. For these loans, the level of long-term interest rates will have a particular bearing on the cost of new financing. Long rates have increased over the past year but have fallen somewhat since the September Report.

The Oslo Børs Benchmark Index is a little higher than in September but has shown some volatility in the period, with substantial differences in performance across sub-indexes. Aquaculture equities fell sharply after the Government announced a resource rent tax on the aquaculture sector, while manufacturing, technology and materials equities have posted strong advances.

1 Period: 2016 Q1 – 2025 Q4. Projections from 2022 Q3 for MPR 3/22 and from 2022 Q4 for MPR 4/22. The mortgage rate is the average rate on outstanding mortgage loans to households from the sample of banks and mortgage companies included in Statistics Norway’s monthly interest rate statistics.

2 Period: December 2013 – October 2022.

3 Period: 1 January 2016 – 31 December 2025. Five-day moving average. Latest observation on 9 December 2022. Projections from 2022 Q3 for MPR 3/22 and 2022 Q4 for MPR 4/22. The premium in the Norwegian money market rate is the difference between the three-month money market rate and the expected policy rate.

2.3 Krone exchange rate

Prospects for a stronger krone

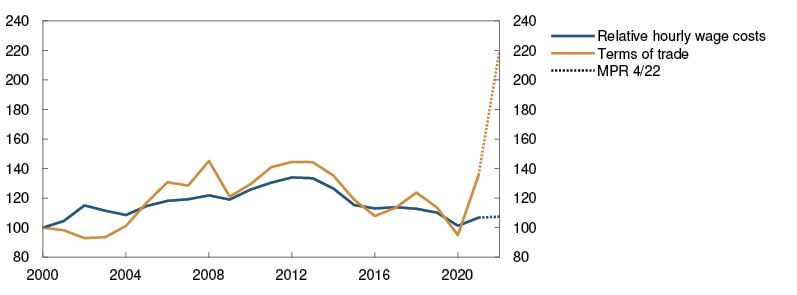

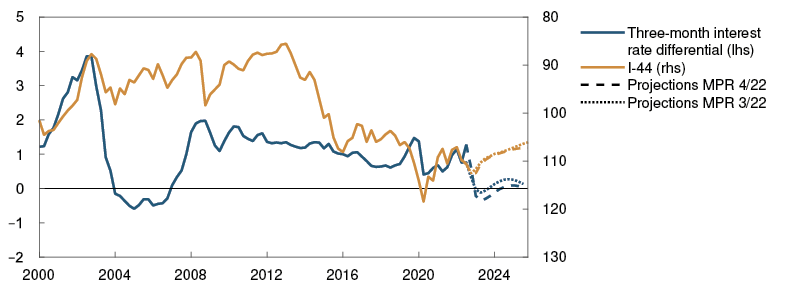

The krone exchange rate, as measured by the import-weighted exchange rate index I-44, has weakened since the turn of the year, and the period has been marked by considerable volatility. Movements in the krone reflect a more pronounced rise in interest rates among trading partners than in Norway. In addition, high inflation in many countries and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have given rise to substantial financial market uncertainty. The uncertainty has contributed to a higher NOK risk premium.

On the other hand, high petroleum prices through 2022 have led to a considerable improvement in Norway’s terms of trade. Over time, there has been a relatively close correlation between the terms of trade and the real exchange rate (Chart 2.4). The krone has not appreciated in 2022, as historical correlations with the terms of trade might suggest. This may reflect substantial uncertainty about the persistence of the rise in petroleum prices and developments in other drivers of the krone exchange rate.

Chart 2.4 Weaker krone than implied by terms-of-trade gains4 Relative hourly wage costs in manufacturing and terms of trade. Index. 2000 = 100

Since the September Report, the krone exchange rate has shown considerable volatility, but the krone is now close to the levels seen in September. Movements in the krone overall are in line with the projections in the September Report, despite the decline in petroleum prices and the larger increase in foreign interest rates than in domestic rates. The krone is expected to remain close to its current level in the near term.

Further out, uncertainty in global financial markets is expected to diminish and the krone to appreciate (Chart 2.5). The projections are little changed from the September Report, but there is considerable uncertainty about future movements in the exchange rate. The projections imply that interest rates in Norway will be lower than among trading partners through 2023, for the first time since before the financial crisis. This may suggest a weaker krone than envisaged. On the other hand, global inflation may abate faster than anticipated, which may reduce the turbulence in global financial markets further and lead to a stronger krone. Episodes of low NOK market liquidity may contribute to amplifying krone exchange rate volatility.

Chart 2.5 Stronger krone than implied by the interest rent differential5 Import-weighted exchange rate index (I-44). Difference between three-month money market rate in Norway and among trading partners. Percentage points

4 Period: 2000 – 2022. Projections for 2022. Relative hourly wage cost in Norwegian manufacturing compared with manufacturing among EU trading partners in a common currency. Terms of trade are defined as export prices devided by import prices.

5 Period: 2000 Q1 – 2025 Q4. Projections from 2022 Q3 for MPR 3/22 and 2022 Q4 for MPR 4/22. A rising index value for I-44 indicates a depreciating krone. The right-hand scale is inverted. Interest rate differential between Norway and its main trading partners.

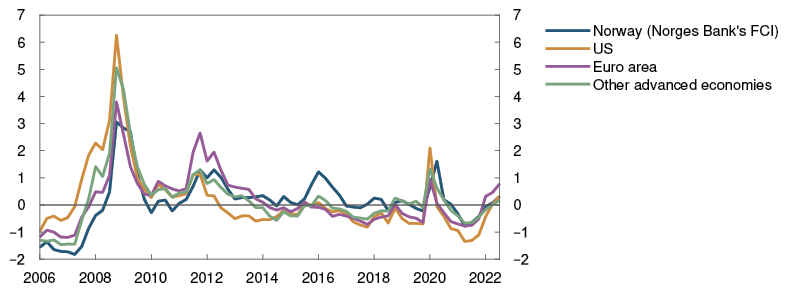

A financial conditions index (FCI) for Norway

Financial conditions provide an indication of the ease with which finance can be accessed by banks, households and firms and on what terms. The policy rate is important because it determines the short-term risk-free interest rate that serves as a benchmark for other financial prices, but it is not enough to look at the policy rate alone. A number of other variables can also affect financial conditions. Norges Bank has therefore developed a financial conditions index (FCI) to obtain a more comprehensive impression of the price and availability of different types of financing beyond that indicated by the policy rate. Empirical exercises show that the index can help to explain the evolution of aggregate activity in the Norwegian economy.

An FCI may be useful for separating important signals from noise across financial markets and is therefore actively used by many central banks, institutions and major investment banks. For example, credit, liquidity and exchange rate risk premiums may vary considerably over time and contribute to greater interest rate volatility than implied by changes in the policy rate. Furthermore, changes in risk appetite and expectations regarding future earnings and interest rates may result in wide swings in asset prices, regardless of the policy rate. Financial prices can, in turn, also influence consumption and real investment.

Our aim was to construct a relatively simple index that covers the key financial variables in the Norwegian economy. The preferred index therefore contains relatively few variables and shares many features with indexes used by Sveriges Riksbank and Danmarks Nationalbank. Since the FCI is designed to capture the evolution of overall financial conditions beyond the evolution of the policy rate, interest rates in the index are adjusted for the policy rate and market policy rate expectations. We have also calculated indexes based on a larger sample of variables, but the result does not change appreciably. Since interest rates are included as risk premiums and asset prices are normalised relative to an estimated trend, variations in inflation will in principle not affect how the index is interpreted.

Household lending rates and house prices are included as indicators of household financial conditions. Since many households have floating-rate loans, a change in lending rates is likely to have a considerable impact on overall household borrowing costs. Changes in house prices will affect household balance sheets and households’ ability to borrow since housing is also commonly used as collateral. As measures of corporate financial conditions and borrowing costs, the index includes bond yields and bank lending rates. We also include measures of banks’ borrowing costs to quickly capture changes in borrowing costs before any pass-through to changes in household and corporate lending rates. Premiums in the covered bond and senior bank bond markets are therefore included in the index. In addition, we have included equity prices based on the Oslo Børs Benchmark Index, both the level measured as a deviation from a moving average and volatility. Equity prices can provide information on costs associated with equity financing. We have also included the volatility in the import-weighted exchange rate index as an indicator of the cost of hedging against foreign exchange rate movements.

In order to represent the typical variation in the variables in a single index, we perform a principal component analysis of standardised variables.1 A simple average of the variables could have been used or weights could have been estimated using different methods, but our estimates indicate that the index would not have been materially different.

Chart 2.A shows the evolution of the FCI since January 2003 at a monthly frequency. The last value is the average of daily observations in the period to 9 December 2022. The index is decomposed into submarket contributions. Since the index is standardised, it will vary around zero. It can therefore not be interpreted directly but provides an indication of the tightness or accommodativeness of financial conditions compared with a historical average. The credit market is especially important for explaining the evolution of the index over time. This reflects the bank-based nature of the financial system in Norway and the impact of changes in the money market premium on many interest rates. The decomposition suggests that all submarkets contributed to more accommodative financial conditions in the period leading up to the financial crisis and thus to dampening the tightening from a higher policy rate. In 2008, financial conditions became considerably tighter before normalising through 2009. The second substantial tightening of the index was in March 2020, but compared with the financial crisis, this tightening was brief. Through this autumn, the FCI has risen, which may have amplified the contribution from monetary tightening in the period. So far in December, the index has fallen back somewhat.

Chart 2.A Tighter financial conditions in autumn2 Financial conditions index. Standard deviation from mean

Chart 2.B shows Norges Bank’s FCI for Norway along with similar indexes developed by the IMF at a quarterly frequency. The chart shows that even if the indexes include somewhat different variables, financial conditions in Norway appear to have tracked developments abroad. The exception is the oil price decline in 2015, where financial conditions tightened more in Norway. In 2022, overall financial conditions have tightened somewhat, both in Norway and globally.

Chart 2.B Financial conditions are tightening in Norway and abroad-1 Financial conditions index. Standard deviation from mean

In order to evaluate the properties of the new index, we have investigated the degree to which it helps to explain aggregate activity in the Norwegian economy as measured by mainland GDP. In a forthcoming article-1, Bowe et al (2022) conduct an exercise where what can be characterised as unexpected variation in the FCI, ie shocks, is separated from what can be explained by other macroeconomic variables using a SVAR (structural vector auto-regressive) model. The model also includes the policy rate and mainland GDP. In the exercise, we show that shocks to the FCI affect economic growth. The negative impulse to economic activity from a contractionary financial shock is greater than the boost to activity following a corresponding expansionary financial shock (asymmetric response). Furthermore, in instances of contractionary financial shocks, the proportional decline in GDP growth will be greater the more pronounced the tightening (non-linear response). Based on this model, an unexpected 1 point rise in the index implies that GDP will fall by 0.8% after one year. The effect of an unexpected 1 percentage point increase in the policy rate is stronger and somewhat more persistent. After one year, GDP falls by 1.3%. These effects are highly uncertain.

The index can supplement analyses of financial conditions already included in our modelling system. The Bank’s main model NEMO includes the household lending rate and a weighted corporate rate based on lending rates and bond yields. This means that changes in risk and money market premiums that affect these interest rates will be covered by the monetary policy analysis. The same applies to changes in bank funding costs, which can also affect lending rates. NEMO also includes house prices. But the index can help us to provide a somewhat broader indication of financial conditions and provide early signals of risk and tightness of financial conditions. In the event of more pronounced changes in the index, eg associated with changes in market volatility and larger shifts in equity markets, it can also provide new signals. As mentioned, large increases in the index in particular can signal downside risks to the real economy.

1 This means that an average is subtracted from all variables, and the variables are divided by their standard deviation, which puts all variables on the same scale.

2 Period: January 2003 – December 2022. Monthly average. December is the average of observations up to and including 9 December 2022.

-1 Period: 2006 Q1 – 2022 Q3. Quarter-average.

-1 In a forthcoming Norges Bank Staff Memo (Bowe, Gerdrup, Maffei-Faccioli and Olsen, 2022) the index and SVAR analysis are documented in more detail.

3 The Norwegian economy

Consumer prices have risen rapidly, and inflation is markedly above the target of 2%. At the same time, unemployment is low, and the employment rate is high. Wage growth has increased and is projected to increase further next year.

High consumer price inflation and higher interest rates are curbing demand, and the Norwegian economy is assessed to have reached its cyclical peak. House prices have declined in recent months, and household consumption is expected to drift down ahead. Mainland investment is expected to decline from a high level.

From next year, inflation is expected to fall and approach the inflation target further out, on the back of lower capacity utilisation, an easing of international price pressures and a fall in energy prices. Unemployment is projected to rise somewhat, albeit from a low level.

3.1 Output and demand

Slowdown in the mainland economy

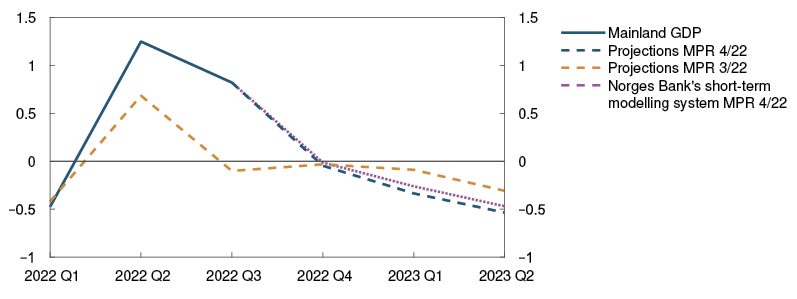

Activity in the Norwegian economy has recovered from the pandemic. Revised national accounts figures indicate that activity has been higher through 2022 than assumed in the September 2022 Monetary Policy Report. In 2022 Q3, the mainland economy grew by 0.8%.

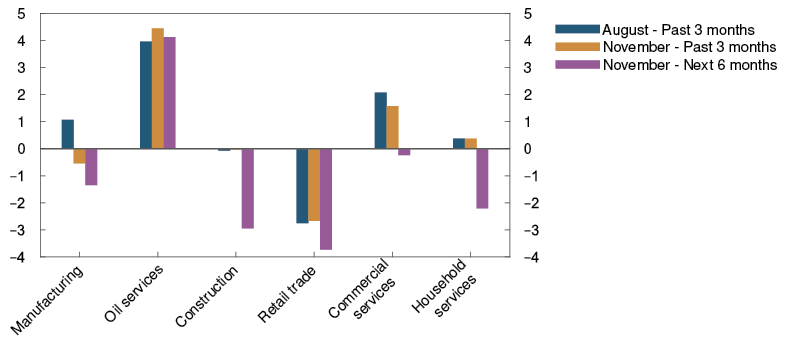

At the same time, Norges Bank’s Regional Network contacts report that growth has slowed and they expect activity to decline markedly over the next half year (Chart 3.1). Enterprises in retail trade and other household services expect lower demand owing to weaker household purchasing power. Contacts in the construction industry report lower order volumes due to weak new home sales and lower public demand. Manufacturing is facing dampened prospects due to weaker developments in Norway and abroad, but strong demand from the energy sector softens the decline and contributes to strong growth in oil services.

Chart 3.1 Prospects for a slowdown in activity1 Reported and expected growth according to the Regional Network. Annualised. Percent

The Norwegian economy is assessed to have reached its cyclical peak, with activity declining through winter. House prices have fallen since the September Report, and expectations surveys indicate that that the economy is cooling down. Combined with higher inflation, activity is likely to fall to a further extent in the first half of 2023 than projected in the September Report. This is consistent with the forecasts from our modelling system for short-term forecasting, where a broad set of empirical models are weighted based on their historical forecasting performance (Chart 3.2).

Chart 3.2 Mainland GDP expected to decline2 GDP for mainland Norway. Quarterly change. Seasonally adjusted. Percent

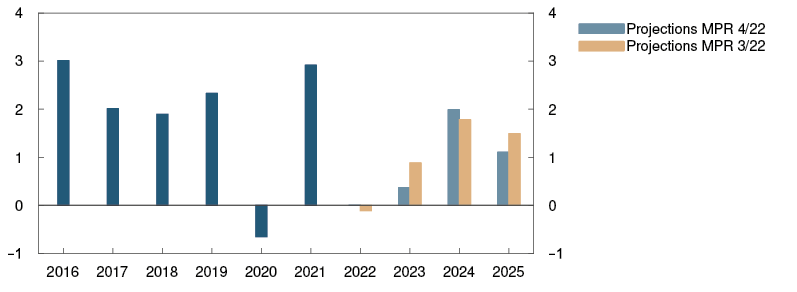

Mainland Norway GDP is projected to increase by 3.6% this year, primarily reflecting an increase in household consumption and business investment (Chart 3.3). Next year, lower consumption results in a 0.2% decline in mainland economic activity. In 2024 and 2025, economic activity is projected to pick up gradually. Increased investment in the petroleum industry and activities related to climate transition lift growth in the years ahead.

Chart 3.3 Lower household consumption reduces growth ahead3 GDP for mainland Norway. Annual change. Percent. Contribution to annual change. Percentage points

High inflation and higher interest rates curb consumption

Household consumption has increased considerably over the past year and continued to grow in 2022 Q3. This primarily reflects an increase in services consumption and spending abroad, while goods consumption has decreased so far this year.

Consumption has been higher than projected despite the fact that high inflation and an increase in interest expenses are reducing household purchasing power. The saving ratio has fallen and was negative in Q3. This may indicate that households have maintained consumption by drawing on accumulated savings. Card transaction data suggest that consumption growth has edged down through autumn, and household confidence indicators are at very low levels.

In the projections, consumption falls by about 1.5% in 2023, after growing by 6.5% in 2022 (Chart 3.4). Real disposable income declines markedly in 2023. A decline in house prices reduces household wealth and dampens consumption as a large share of wealth and debt is related to housing. The projections for consumption assume that households will continue to draw on accumulated savings, especially in 2022 and 2023. The saving ratio turns negative in 2023 and the ratio stays lower in the years ahead than in the years before the pandemic (Chart 3.5). Higher income and lower inflation are then expected to contribute to growth in consumption up to 2025.

Chart 3.4 Lower consumption growth next year4 Household consumption. Constant 2019 prices. Seasonally adjusted. Seasonally adjusted. In billions of NOK

Chart 3.5 Sharp fall in household saving5 Household saving ratio excluding dividends. Percent

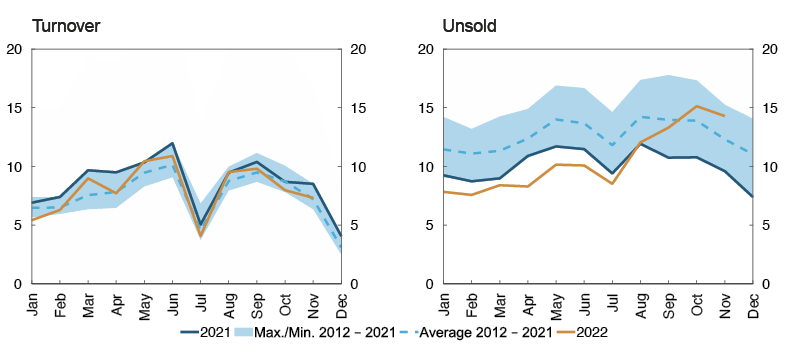

Weaker housing market

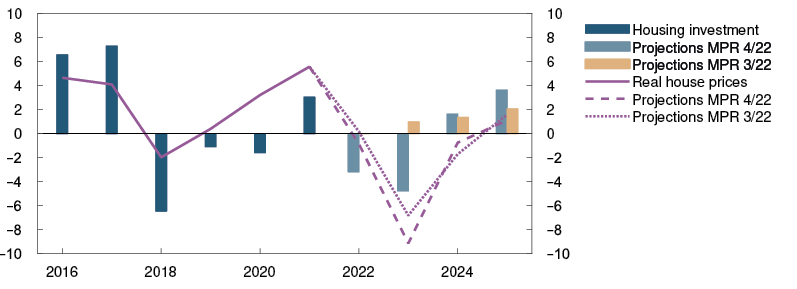

House prices have fallen by 2.6% since August, and the number of unsold homes has increased markedly. Higher interest rates are expected to continue to pull down house prices in the period to autumn 2023, but house prices will still be 12% higher than pre-pandemic levels. House prices rise gradually thereafter. The projections for house prices are lower than in the September Report (Chart 3.6). See Section 5 for a more detailed discussion of the housing market.

Chart 3.6 Steeper fall in housing investment6 Housing investment and real house prices. Annual change. Percent

Housing investment has fallen more through 2022 than previously assumed. Falling house prices, labour shortages and high material costs have probably contributed to curbing investment recently. Housing investment is set to continue to fall into 2023 on the back of recent lower house prices and very low new home sales. Housing investment is projected to recover somewhat further out.

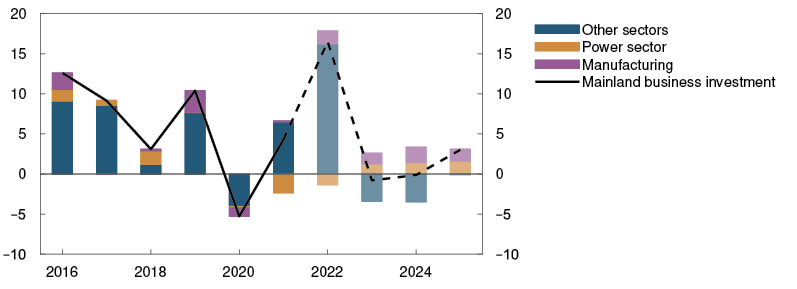

Business investment slows from high levels

Business investment is at a high level, boosted by a substantial and far stronger-than-expected increase in investment in the services sector in Q1. Regional Network enterprises expect slightly lower investment in retail trade and the services sector ahead.

Strong cost inflation, higher costs for new funding and weaker profitability for many firms are expected to weigh on investment. Business investment edges down in 2023, after rising by almost 17% in 2022 (Chart 3.7). Investment in activities related to climate transition in Norway and abroad are pulling up investment. A marked increase in manufacturing is projected in the years ahead, primarily reflecting large investments in batteries, hydrogen and carbon management (see box in Monetary Policy Report 2/21). Prospects for high electricity demand will likely boost electricity investment from 2023.

Chart 3.7 Investment in sectors other than power and manufacturing will edge lower in 20237 Business investment in mainland Norway. Annual change. Percent. Contribution to annual change. Percentage points

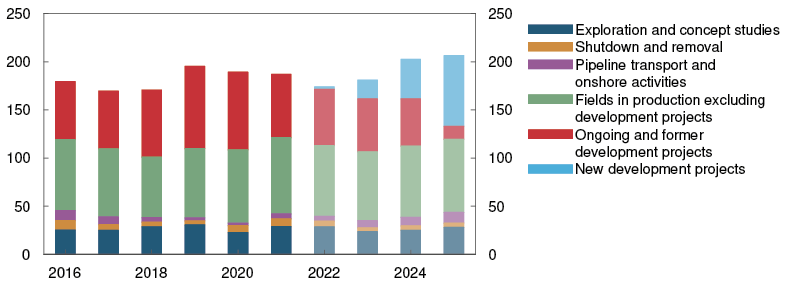

Petroleum investment has declined in recent years as several large projects on the Norwegian continental shelf have been completed. In order for new development projects to benefit from the temporary tax changes introduced in 2020, development plans must be submitted by end-year. As a result, given the many new projects now in the pipeline, petroleum investment is expected to show solid growth in the coming years (Chart 3.8), but the growth projections are lower than in the September Report as some planned development projects have been postponed or cancelled.

Chart 3.8 New development projects increase petroleum investment8 Petroleum investment. Constant 2022 prices. In billions of NOK

Normalisation of external trade

Oil services exports have increased considerably in 2022 on the back of a strong recovery in the global petroleum industry. Normalisation of activity among our trading partners and higher travel activity than during the pandemic have boosted exports from other mainland enterprises. Demand from the petroleum and renewables sectors abroad underpins export growth in 2023, while weaker growth prospects for our trading partners dampen growth for other mainland exports in the coming years. In 2025, export growth picks up, partly reflecting exports from new battery factories. An appreciation of the krone through the projection period dampens export growth slightly.

Cross border shopping and Norwegians’ travel habits are normalising following the pandemic, providing a strong boost to import growth between 2021 and 2022. In the period ahead, imports are projected to grow moderately owing to sluggish growth in the Norwegian economy. Import growth is underpinned by a high level of investment in mainland enterprises and petroleum activities.

Weaker growth in public demand

Growth in public demand has been weak so far in 2022 and is projected to remain weak in 2023 (Chart 3.9). High inflation pushes up public sector costs and will likely dampen public demand in 2023. Against the background of weaker cyclical developments, public demand growth is expected to increase in 2024.

Chart 3.9 Weak growth in public demand9 Public demand. Annual change. Percent

The Government’s budget agreement with the Norwegian Socialist Left Party entails somewhat higher public spending than set out in the Government’s fiscal budget proposal for 2023, but still entails a reduction in public spending next year. Government support for household electricity bills will continue, dampening the effect of high electricity prices on consumer prices. The other proposed changes in household taxes and transfers are not expected to have a material impact on income and consumption prospects, while changes in direct and indirect company taxation may to some extent dampen investment activity in the private sector. Overall, the fiscal stance appears to be broadly in line with the assumptions in the September Report.

The projections are uncertain

The Norwegian economy is slowing down, but the extent of the slowdown is uncertain. More enterprises than normal in the Regional Network, particularly in the business services sector, are uncertain about the evolution of demand ahead. Lower business sector demand may lead to a sharper fall in investment than projected in this Report. There is also uncertainty associated with households’ response to higher inflation, increased interest rates and lower house prices. It is uncertain to what extent households will draw on savings to maintain consumption when their purchasing power declines. Consumption may prove higher than projected if households save a smaller share of their income than assumed.

1 Period: May 2022 – May 2023. Growth past three months and expected growth next six months.

2 Period: 2022 Q1 – 2023 Q2. Projections from 2022 Q3 for MPR 3/22 and from 2022 Q4 for MPR 4/22 and for Norges Bank’s modelling system for short term projections. Our modelling system is based on historical relationships. It weights together empirical models based on previous forecasting properties.

3 Period: 2016 – 2025. Projections from 2022. Petroleum investment includes investment in international shipping.

4 Period: 2016 Q1 – 2025 Q4. Projections from 2022 Q4 for MPR 4/22. Projections from 2022 Q3 for MPR 3/22.

5 Period: 1993 – 2025. Projections from 2022.

6 Period: 2016 – 2025. Projections from 2022. Real house price is nominal house price deflated with CPI.

7 Period: 2016 – 2025. Projections from 2022.

8 Period: 2016 – 2025. Projections from 2022. Data for 2016–2021 from Statistics Norway’s investment survey and deflated by the price index for petroleum investment in the national accounts. The price index is projected to increase by 5,2% from 2021 to 2022 and by 2% in 2023.

9 Period: 2016 – 2025. Projections from 2022.

3.2 Labour market

A tight labour market

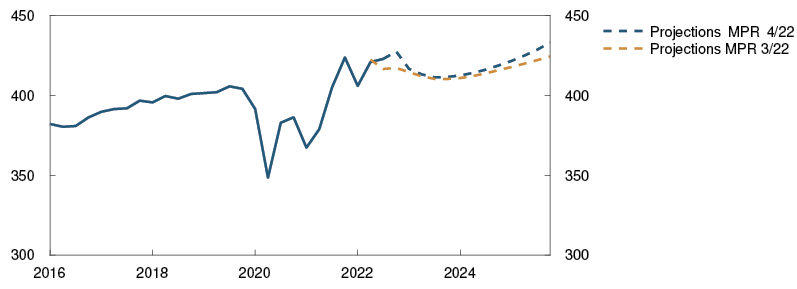

Unemployment is low, and the employment rate is high (Chart 3.10). Since the reopening in summer 2021, employment has increased substantially, with 98 000 more employed now than before the pandemic. In 2022 Q3, employment rose more than projected in the September Report, and preliminary figures suggest that employment continued to rise somewhat in October.

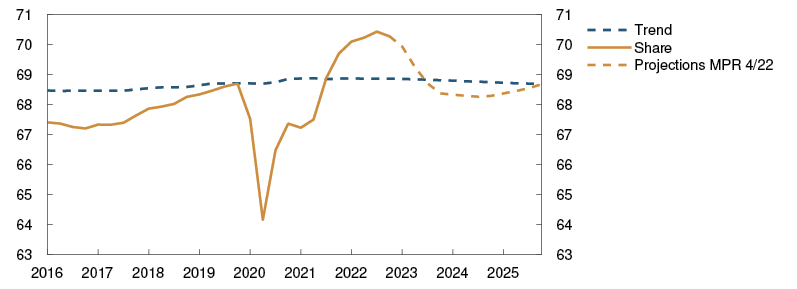

Chart 3.10 High employment rate10 Employed as a share of the population aged 15–74. Percent

The sharp rise in employment reflects the further decline in unemployment as well as a large number of labour force entrants. Residents that were previously outside the labour force have become employed, and the number of temporary foreign workers has increased. In 2022 Q3, the number of temporary foreign workers increased further, but the rise was slightly less pronounced than projected in September.

In November, 45 700 persons were registered as fully unemployed with the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration (NAV). Adjusted for normal seasonal variations, the unemployment rate remained at 1.6%. This is the lowest unemployment rate since before the financial crisis in 2008 and slightly lower than projected in September. While overall unemployment has remained low, the inflow of new fully unemployed job seekers has recently increased, which may be a sign that the labour market is loosening.

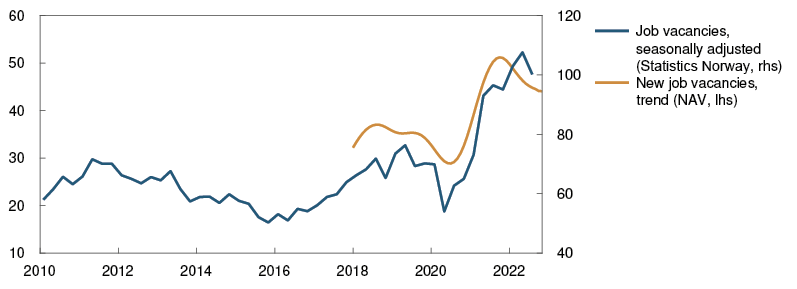

Labour demand is declining from a high level

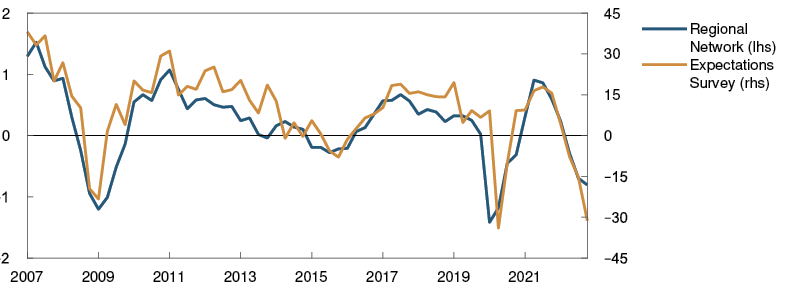

Labour shortages have eased in recent months, and in November, 39% of Regional Network contacts reported that activity was being constrained by labour shortages. This share is smaller than before summer, when over half of contacts reported labour constraints. Nevertheless, the share is still high.

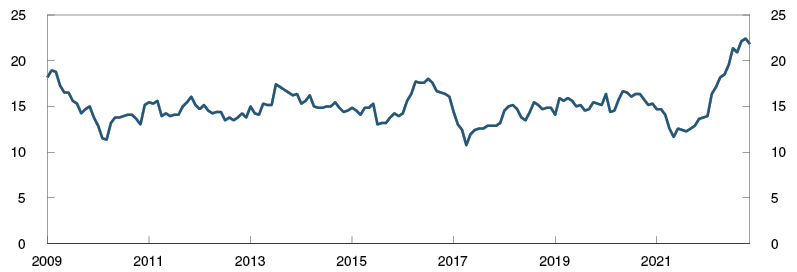

Moreover, the number of job vacancies is declining from a high level (Chart 3.11). According to Statistics Norway’s sample job vacancy survey, the number of job vacancies fell in 2022 Q3. However, the number remains close to the highest level since the survey was first conducted in 2010. NAV statistics show that although the number of newly advertised vacancies is still high, the number has declined in recent months.

Chart 3.11 Labour demand has declined11 Number of job vacancies in thousands

Prospects for somewhat higher unemployment

In the coming months, employment growth is projected to weaken and the number of employed to begin to decline further out. In November, Regional Network contacts reported that employment had edged up in recent months but expect broadly stable employment over the next three months. The employment outlook was weaker in November than in August in all private sectors except for oil services. Norges Bank’s Expectations Survey also points to weaker employment growth ahead and indicates that the number of employed will begin to decline further out.

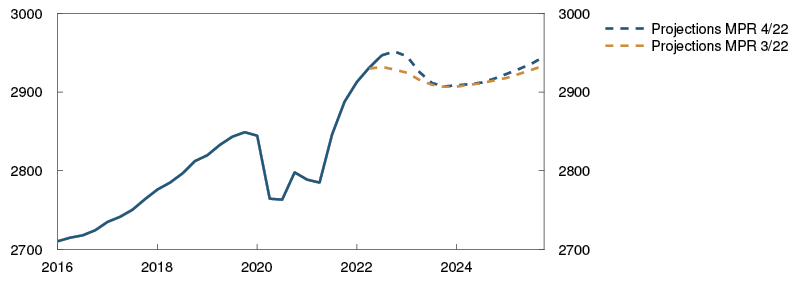

The Norwegian economy is assessed to have reached its cyclical peak, which implies weaker employment developments ahead and some decline in the number of employed in the coming years (Chart 3.12). More employees are expected to return to work thereafter as economic activity picks up. In the projections, the employment rate declines somewhat in the coming years and then stays close to its pre-pandemic level (Chart 3.10).

Chart 3.12 Decline in employment ahead12 Employed. In thousands. Seasonally adjusted

The war in Ukraine has led to a rise in the number of refugee arrivals to Norway. There are prospects that the number will increase more in both 2022 and 2023 than projected in September. Some of these refugees are expected to find a job in the coming years. The number of temporary foreign workers in Norway is also projected to edge up further.

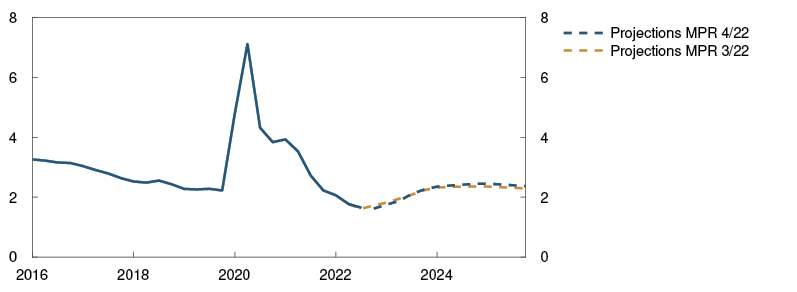

In the projections, the unemployment rate increases gradually in the coming years, and then remains around 2.4% (Chart 3.13). This is close to the level of unemployment during the last few years prior to the pandemic.

Chart 3.13 Prospects for somewhat higher unemployment13 Registered unemployed as share of the labour force. Seasonally adjusted. Percent

10 Period: 2016 Q1 – 2025 Q4. Projection from 2022 Q4 – 2025 Q4.

11 Period: January 2010 – November 2022. Data from January 2018 for NAV. Owing to a break in NAV’s statistics at the beginning of 2018, only data since January 2018 are included. Statistics Norway’s statistics are presented as quarterly figures, while NAV’s statistics are monthly.

12 Period: 2016 Q1 – 2025 Q4. Projections for employment from 2022 Q3 for MPR 3/22 and from 2022 Q4 for MPR 4/22.

13 Period: 2016 Q1 – 2025 Q4. Projections from 2022 Q3 for MPR 3/22 and 2022 Q4 for MPR 4/22.

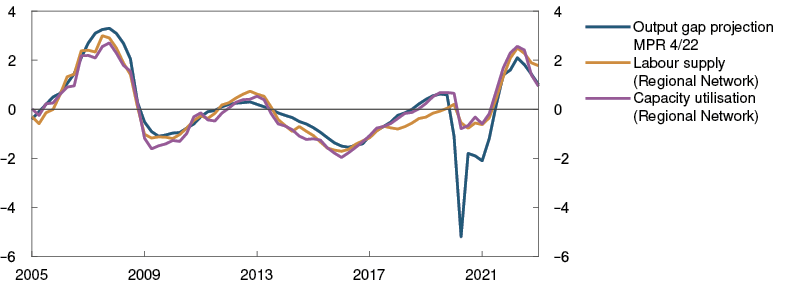

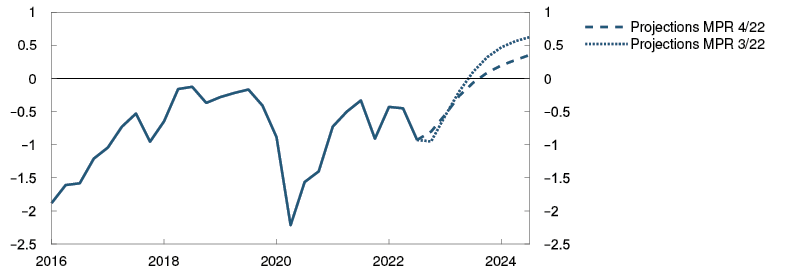

Lower capacity utilisation ahead

Output is assessed to be above potential, but the output gap is now declining. The slowdown in the economy appears to occur somewhat later than expected in the September Report. Output is projected to fall below potential in the course of the latter half of 2023 and remain below potential in the following years.

The output gap is a measure of the difference between actual output (GDP) and potential output. Potential output is determined by trend productivity and trend employment. Potential output and the output gap cannot be observed and must therefore be estimated. The Bank’s output gap estimates are based on an overall assessment of various indicators and models. Particular weight is given to labour market developments.

Output is assessed to have reached potential in autumn 2021 and continued rising into 2022. Output in 2022 Q3 is assessed as broadly unchanged from Q2. In this period, unemployment fell, and employment and GDP growth were stronger than expected. At the same time, capacity problems among some Regional Network contacts also eased. Our overall assessment is that the output gap in Q3 was just above 2%, a little higher than projected in the September Report.

So far in Q4, there are signs that the output gap is declining from a high level (Chart 3.A). In November, Regional Network contacts reported a marked decline in capacity utilisation in most sectors. At the same time, labour shortages among Regional Network contacts have eased.

Chart 3.A Regional Network reports that capacity utilisation has slowed1 Percent

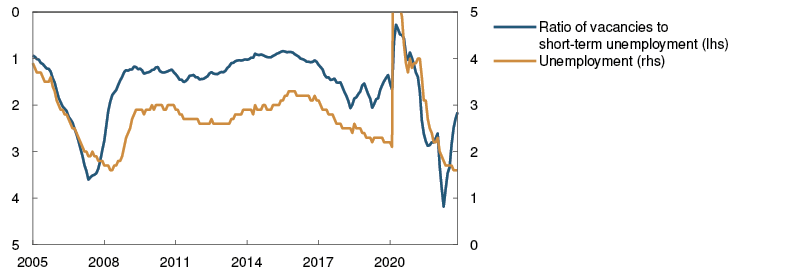

There has also been a decline in the number of job vacancies and an increase in the number of short-term unemployed, resulting in a fall in the ratio of vacancies to short-term unemployed (Chart 3.B). This may indicate an increase in unemployment ahead.

Chart 3.B Lower ratio of vacancies to short-term unemployed2 Unemployment as a percentage of the labour force. Seasonally adjusted

Overall, the output gap is projected to decline quickly over the coming quarters and bottom out at negative 0.8% during the latter half of 2024. Capacity utilisation in the coming years will be a little lower than envisaged in September (Chart F in "Monetary policy assessment").

An expected decline in household consumption is the main reason why demand and output are expected to be lower in the coming year. Even though capacity utilisation stops falling further out and then moves up a little, output is expected to still be below potential at the end of 2025.

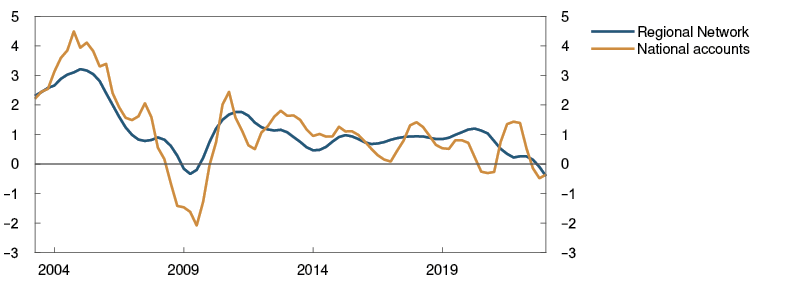

Since the September Report, potential output in 2022 has been revised up. Information from the national accounts and Regional Network indicates that productivity growth will be 0.5 percentage point higher in 2022 than envisaged in September. Even though potential output in 2022 has been revised up, there are still signs that productivity growth will be weak ahead. The historical relationship between productivity in the Regional Network and the national accounts indicates that productivity growth will be weak into 2023 (Chart 3.C). In the coming years, trend productivity growth is expected to be around 0.6%.

Chart 3.C Weak productivity growth-1 Four-quarter change. Moving average. Percent

The authorities have revised up their projection for the inflow of Ukrainian refugees. In this Report it is assumed that a large number will eventually enter the labour market, so that potential output has been revised up towards the end of the projection period. Prospects for slightly fewer temporary foreign workers than projected earlier pull in the opposite direction.

1 Period: 2005 Q1 – 2023 Q1. Regional Network capacity utilisation indicators have been converted to output gaps using a simple model estimation.

2 Period: January 2005 – November 2022. Short-term unemployed are job seekers that have been unemployed for less than 26 weeks. Job vacancies comprise a NAV series trend for new job vacancies estimated by Norges Bank, Statistics Norway’s job vacancy survey and historical job vacancy statistics. See further description in Chart 3.B in MPR 2/22.

-1 Period: 2003 Q2 – 2023 Q1. Productivity growth is the difference between four-quarter change in production and four-quarter change in employment.

3.3 Prices and wages

High inflation

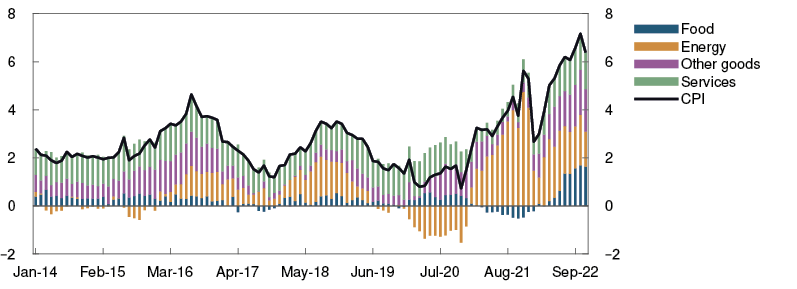

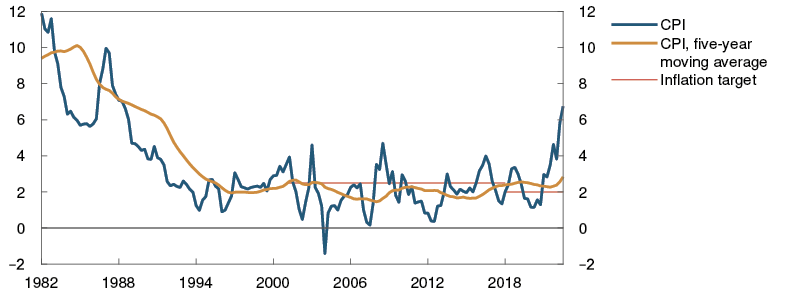

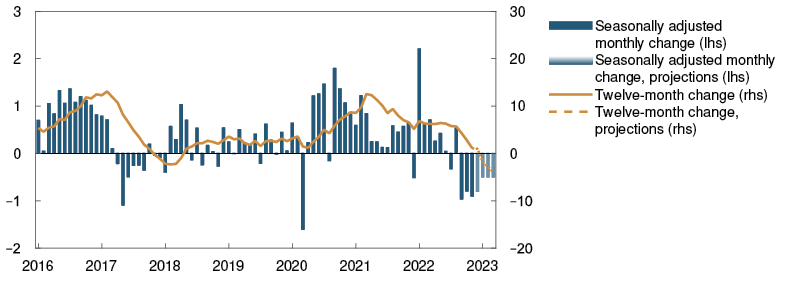

Consumer price inflation is now rising rapidly and has been appreciably higher than projected in the September Report. In November, the consumer price index (CPI) was 6.5% higher than one year earlier. The twelve-month change was still somewhat lower than in October. The rapid rise in prices reflects high energy and non-energy commodity prices, strong demand and elevated international price pressures. Inflation is broad-based, and both goods and services inflation have accelerated (Chart 3.14).

Chart 3.14 Broad rise in consumer prices1 CPI. Twelve-month change. Pecent. Contribution to twelve-month change. Percentage points

The 12-month rise in the CPI adjusted for tax changes and excluding energy products (CPI-ATE) also edged lower in November after a marked rise through the year. In November, the 12-month rise in CPI-ATE inflation was 5.7%. Other underlying inflation indicators have risen in line with CPI-ATE inflation (Chart 3.15).

Chart 3.15 Underlying inflation has moved up2 CPI and underlying inflation indicators. Twelve-month change. Percent

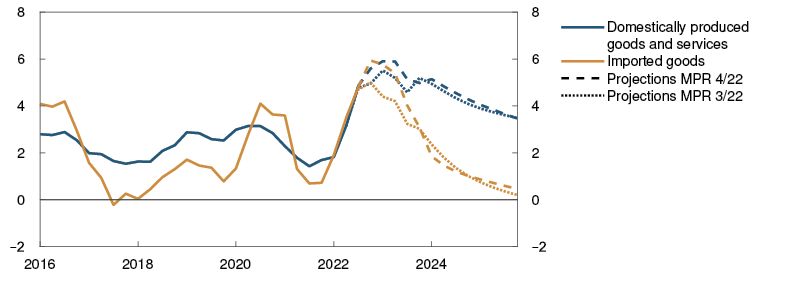

The rise in prices for both imported and domestically produced goods and services is high and faster than expected. Prices for food and non-alcoholic beverages in particular rose sharply over the past year. Prices for transport services, furniture and hotel and restaurant services have also risen rapidly. As these price components are normally not affected by the same factors, the current rapid rise in all of these prices indicates that there is a range of different factors, including prices for various intermediate goods, driving up prices right now.

Inflation expectations for the next years have increased (Chart 3.D). Inflation expectations two and five years ahead are now above the 2% target according to Norges Bank’s Expectations Survey for Q4.

Inflation is difficult to forecast

Inflation has been higher than projected for some time. This may be partly because there is little experience with the extent to which high electricity prices and freight rates affect consumer price inflation (see boxes in Monetary Policy Report 4/21 and Monetary Policy Report 3/22). At the same time, it has been a long time since prices have risen as rapidly as is currently the case. Experience from the 1980s has shown that price changes in one sector can spread more quickly to other sectors in periods of high inflation (see "Uncertainty about price dynamics when inflation is high"). If such second-round effects are now in play, various price pressures may have a more pronounced and prolonged effect on inflation today too, than has been the case in recent decades.

In the projections, inflation rises a little further and four-quarter CPI-ATE inflation picks up to 5.9% in 2023 Q1 (Chart 3.16). This is a little higher than indicated by Norges Bank’s empirically based forecasting model.

Chart 3.16 Historical relationships suggest a slower rise in inflation3 CPI-ATE. Four-quarter change. Percent

Freight rates have fallen markedly in recent months, and imported inflation is expected to moderate over the entire projection horizon in response to weaker international price pressures (Chart 3.17). Further out, lower capacity utilisation and a fall in energy prices will have a dampening effect on domestic inflation. On the other hand, higher wage growth and weak productivity growth are expected to contribute to keeping domestic inflation elevated. Overall, four-quarter CPI-ATE inflation is expected to decline gradually to 2.5% at the end of 2025. For most of next year, the projections are higher than in the September Report but are little changed for the remainder of the projection period.

Chart 3.17 Prospects for lower imported inflation4 Domestically produced goods and services and imported goods in the CPI-ATE. Four-quarter change. Percent

Futures prices indicate that electricity and fuel prices pull up CPI inflation through winter. Electricity prices in the CPI are also affected by a number of other factors, such as government support for electricity bills, regional price differences and choice of electricity contract. Owing to unusually large electricity price movements, the uncertainty relating to the overall effect of these prices on CPI inflation in the coming period is higher than normal.

Further out, energy prices are expected to fall markedly. Government support for household electricity bills is dampening CPI inflation. In the projections, government support for electricity bills is reduced somewhat in the summer months next year, in line with the fiscal budget proposal. Four-quarter CPI inflation is expected to remain elevated until 2023 Q1, declining gradually thereafter to 2.4% at the end of 2025.

Higher wage growth in 2023

Wage growth appears to be higher in 2022 than in 2021, partly owing to a very tight labour market. This year’s wage norm rose considerably from 2021 (Chart 3.18). This reflects, among other things, an increase in manufacturing’s ability to pay wages thanks to higher export prices and improved productivity through 2021. Register-based wage statistics indicate that wage growth in the first three quarters of 2022 may have been slightly lower than projected in the September Report, although they still suggest that annual wage growth is on the rise. Many new labour market entrants earn lower-than-average wages. It is assumed that this will in isolation pull down the average wage level somewhat in 2022. Wage growth is projected at 3.9% in 2022.

Chart 3.18 Higher wage growth expected5 Annual wage growth. Percent

According to Norges Bank’s Regional Network and Expectations Survey, wage growth expectations are higher in 2023 than in 2022 (Chart 3.18). The social partners’ wage growth expectations for 2023 have increased since September.

High inflation and continued tight labour market conditions will likely lead to a further rise in wage growth in 2023. Weak productivity growth and prospects for weaker profitability (Chart 3.19) are likely to dampen the rise. Wage growth is projected to rise to 4.7% in 2023, which is close to the social partners’ wage expectations.

Chart 3.19 Weakened business profitability6 Change in operating margins according to the Regional Network and the Expectations Survey

Norway’s terms of trade have improved considerably in 2022, primarily reflecting high gas prices. A little further out in the projection period, increased petroleum revenues are expected to boost activity and lift profitability for mainland firms. In isolation, this points to higher wage growth. Wage growth is still expected to decline from 2024 owing to lower inflation and somewhat higher unemployment. The projection for 2023 has been revised up a little, while projections for the following years are somewhat lower than in the September Report.

There are prospects for a sharp fall in real wages in 2022, after remaining unchanged in 2021 (Chart 3.20). Real wages are expected to remain broadly unchanged in 2023. In 2024 and 2025, real wages are expected to rise again. Overall, the real wage projections for the years 2022 to 2025 are lower than in the September Report.

Chart 3.20 Weak developments in real wages7 Annual change. Percent

Unusually high uncertainty

Developments in price and wage inflation ahead are more uncertain than normal. It is still uncertain how different forces affecting inflation will evolve and impact prices. Inflationary pressures over the past year have been unusually volatile, and the absence of experience with comparable historical episodes makes it difficult to estimate their effect on consumer prices.

At the same time, there is substantial uncertainty about the effects of high inflation on wage and price formation. Inflation expectations for the coming years have increased lately. There is a risk that households and firms will come to expect high inflation and adjust their price and wage setting behaviour accordingly. Inflation dynamics may change more than currently assumed, in which case inflation could stay high for longer, making it difficult to bring it down again.

Inflation may also fall faster and prove lower than currently projected. Energy prices and freight rates, for example, have declined and may also fall faster ahead than currently envisaged. This may lead to weaker external price pressures and a faster decline in inflation than expected.

The effects of higher costs on firms’ prices and wage formation are also uncertain. In the projections for price and wage inflation, higher costs are shared between employers and employees, lowering both business profitability and real wage growth. How those costs are distributed may differ from that envisaged, which could result in a different path for price and wage inflation than expected.

1 Period: January 2014 – November 2022.

2 Period: January 2016 – November 2022. CPI-ATE: CPI adjusted for tax changes and excluding energy products. Average: Average value of 12 -month change for other underlying inflation indicators (CPIM, CPIXE, 20 percent trimmed mean, weighted median, CPI-XV and CPI-common) and CPI-ATE. Indicators: Highest and lowest 12-month change for other underlying inflation indicators.

3 Period: 2022 Q1 – 2023 Q2. CPI-ATE: CPI adjusted for tax changes and excluding energy products. Projections from 2022 Q4. Our modelling system for short term projections is based on historical relationships. It weights together empirical models based on previous forecasting properties.

4 Period: 2016 Q1 – 2025 Q4. CPI-ATE: CPI adjusted for tax changes and excluding energy products. Projections from 2022 Q3 in MPR 3/22 and 2022 Q4 in MPR 4/22.

5 Period: 2016 – 2023. Annual wages: Actual wage growth from Statistics Norway. Norges Bank’s projections from 2022. Norges Bank’s Expectations Survey: Social partners’ wage growth expectations for the current year as measured by Norges Bank’s Expectations Survey in Q4 each year. Regional Network survey: Expected annual wage growth for 2022 as reported in Q4 each year.

6 Period: 2007 Q1 – 2022 Q4. Regional Network: Change in operating margins over the past three months compared with same period a year earlier. Index from –5 (large fall) to +5 (large rise). Expectations Survey: Profitability next 12 months. Share of enterprises that report prospects for improved profitability minus the share that report prospects for lower profitability.

7 Period: 2016 – 2025. Projections from 2022. Real wages: Nominal annual wage growth adjusted for CPI inflation.

Uncertainty about price dynamics when inflation is high

Inflation has risen sharply over the past year and has been higher than expected. At the same time, inflation expectations have also risen considerably since mid-2021 (Chart 3.D).

Chart 3.D Inflation expectations have risen1 Inflation expectations. Percent

We have little recent experience with how inflation dynamics may change when inflation is high and inflation expectations are rising. In periods of low and stable inflation, changes in inflation expectations are not found to have a substantial impact on inflation. We therefore have little information for projecting how changes in inflation expectations affect inflation in the current context. The interaction between expectations and actual inflation is one of several uncertainty factors associated with inflation dynamics when inflation is high.