Financial stability outlook

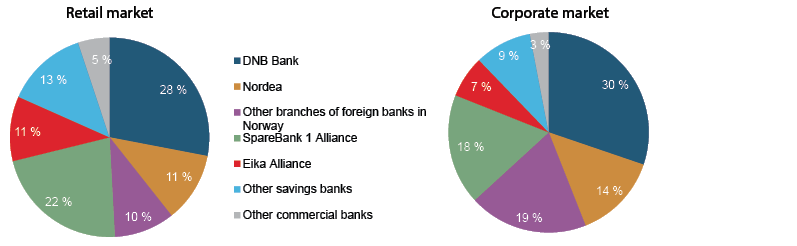

There are considerable spillovers in both Europe and globally from the ongoing war in Ukraine and the after-effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. There is substantial uncertainty about the economic outlook and about how economic agents will respond to higher interest rates and increased costs. The risk of a downturn has increased, and the financial stability outlook has weakened. Financial system vulnerabilities, such as the considerable rise in property prices in recent years and high debt levels among households, may amplify an economic downturn.

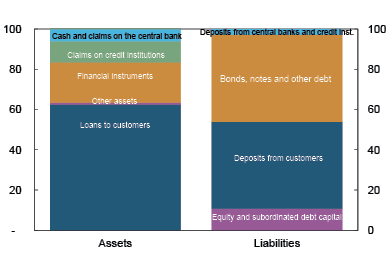

The Norwegian financial system has so far weathered the substantial volatility in financial markets. Solid profitability, capital adequacy and liquidity ensure that banks are resilient, with ample capacity to absorb losses and deal with market stress. It is now especially important that the financial system remains resilient so that it can perform its tasks effectively also in the event of severe economic downturns and crises.

Weaker financial stability outlook

The global growth and inflation outlook is highly uncertain. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the decline in Russian gas supplies to Europe have resulted in high energy prices. Along with strong demand for goods and services and supply-side constraints owing in part to the pandemic, this has led to a surge in consumer prices globally and in Norway. Central banks have raised policy rates to dampen inflation. Activity in the Norwegian economy is high, and unemployment is at a historically low level. At the same time, there are signs that some areas of the economy are cooling down, in the housing market, for example, where prices fell in autumn. Meanwhile, high energy prices are generating record revenues in the oil and gas sector.

The geopolitical situation and uncertainty about the economic outlook have resulted in substantial financial market volatility. Impaired liquidity on many trading venues, also in markets regarded to be the most liquid, has added to the volatility. Over the past year, long-term interest rates and credit premiums on corporate bonds have risen and global equity indexes have fallen. Price volatility in some derivatives markets, which has led to very large margin calls, has created liquidity challenges for many participants globally. Robust trading venues and market participants are the first lines of defence against market stress, and participants must have adequate systems and contingency arrangements for managing liquidity and counterparty risks.

Against the background of a heightened risk over the past year of an economic downturn or other adverse events, it is Committee’s assessment that financial stability outlook has weakened.

Vulnerabilities can amplify a downturn

Owing to vulnerabilities in the Norwegian financial system, a downturn or market stress may have more serious consequences for financial stability. Vulnerabilities are broadly at the same level as at the time of Financial Stability Report 2021, but an increased risk of a downturn implies a greater risk that vulnerabilities materialise. Many households are highly indebted and the vast majority have floating-rate loans. Household leverage is close to a historically high level, and it is high compared with other countries. Higher interest rates and living costs imply tighter finances for many, but the Bank’s analyses show that most households are able to service their debt. High indebtedness makes households vulnerable to loss of income, higher interest rates or a fall in house prices. If many households reduce consumption sharply, firms’ earnings are impaired and banks may face higher losses on corporate exposures. This constitutes a risk to the financial system. A sharp fall in house prices may also lead to substantial bank losses on non-performing residential mortgages of households with a high debt-to-value ratio.

Norges Bank is of the opinion that the Lending Regulation has limited the build-up of household sector vulnerabilities and that the Regulation should continue to apply largely unrevised at present. A broad review of the Regulation should be conducted before it expires in 2024, based on the experience of higher interest rates ahead, among other things.

Banks’ exposures to commercial real estate (CRE) are substantial, and in autumn, property prices have edged down. An economic downturn with a fall in selling prices and rental income may have a substantial impact on this sector and result in large bank losses. Owing to low yields on commercial property, selling prices are vulnerable to higher interest rates and lower risk appetite.

House prices have risen faster than household income over a long period. Prices have fallen this autumn, and the same tendency has been observed in other countries. The projections in the September 2022 Monetary Policy Report point to a moderate fall in house prices in Norway in 2023. Owing to uncertainty about macroeconomic developments and households’ response to higher interest rates, the forecast for house prices is more uncertain than normal. Sharp and sudden declines in house prices may trigger a tightening of household consumption and increase losses on banks’ loan portfolios.

Covered bonds issued by other Norwegian banks account for a substantial portion of banks’ liquidity reserves. This implies that problems at one bank can more easily spread to other banks. If markets are stressed, sales of liquidity reserves to meet liquidity needs may result in greater spillovers than if banks did not have cross-holdings of covered bonds.

The financial infrastructure is secure and efficient. The threat landscape in recent years has become more aggressive and more difficult to gauge. The number of cyber attacks has risen, and they are used as weapon of war and armed conflict. Cyber attacks on critical functions may be a threat to financial stability. There is broad international agreement on the need to strengthen resilience to cyber attacks on the financial sector. This requires an intensive effort to identify risks, regulation and extensive cooperation between various authorities and financial system participants. In collaboration with Finanstilsynet (Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway), Norges Bank has introduced the TIBER framework for testing cyber resilience in the financial system.

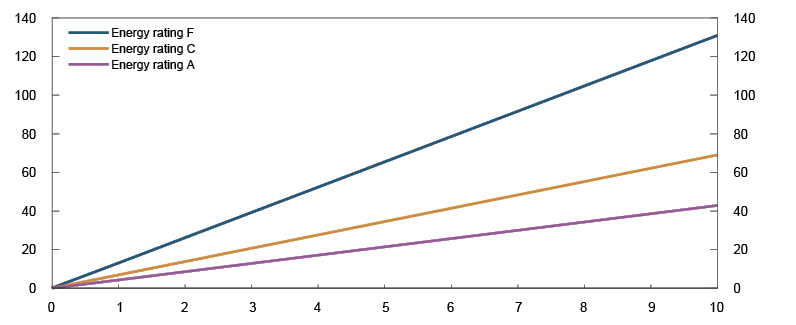

Climate change is one of society’s greatest challenges. Financial institutions must ensure that they are well equipped to assess and mitigate climate risk. Banks’ exposures to the sectors with the highest greenhouse gas emissions are modest, but other firms will also be affected by the climate transition. Well-functioning financial markets are vital for financing investment that can mitigate climate change. Adequate information about climate risk is also important. Energy labelling of buildings makes it easier for banks to assess the climate risk associated with real estate loans. Analyses in this Report show that the share of energy-labelled commercial buildings is low and should be increased. In addition, higher electricity prices make energy efficiency more important in the real estate sector, and the willingness to pay for energy-intensive buildings may fall.

It is important for the financial system to remain resilient

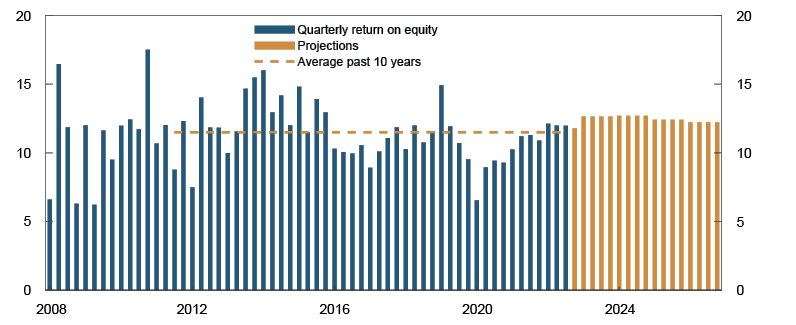

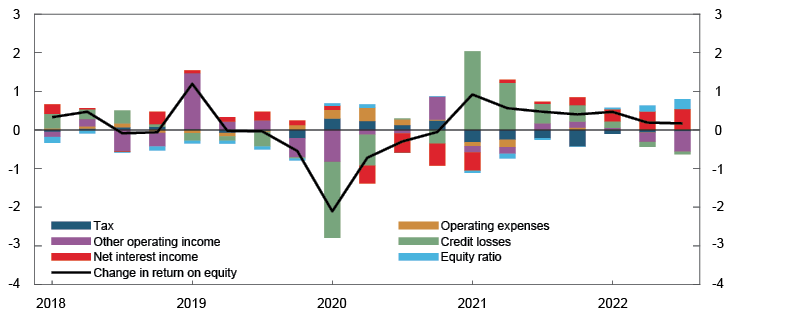

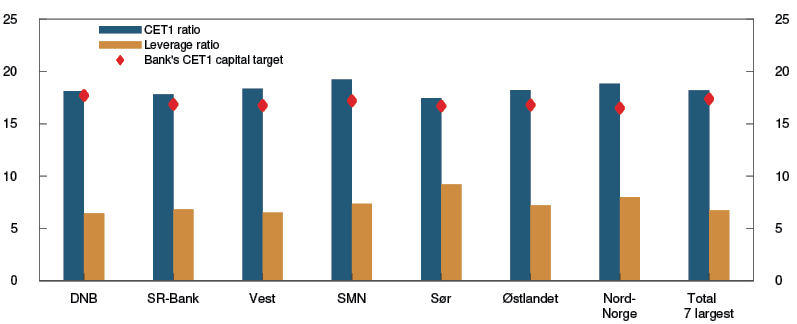

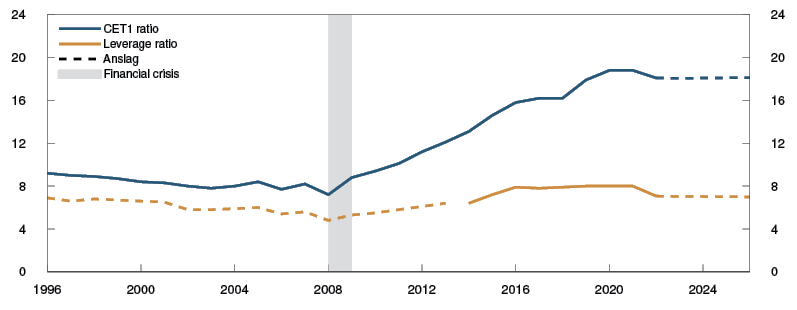

Overall, the financial system is judged to be well equipped to address the risks we are facing. Tightened capital and liquidity requirements over many years have better equipped banks in Norway and many other countries to deal with crises. Norwegian banks’ solid earnings are the first line of defence for absorbing losses and give banks the flexibility to lend to creditworthy firms and households. Banks’ profitability is expected to remain solid, but the risk of losses has risen.

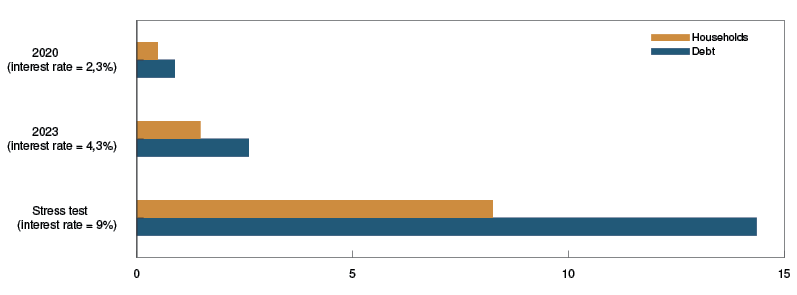

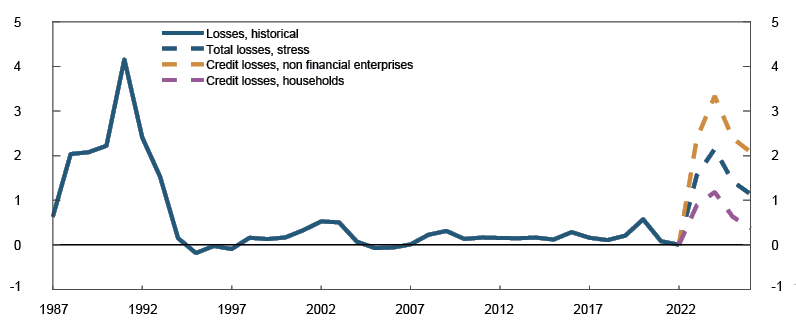

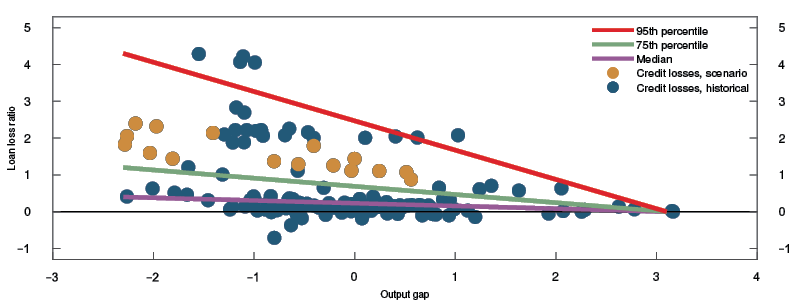

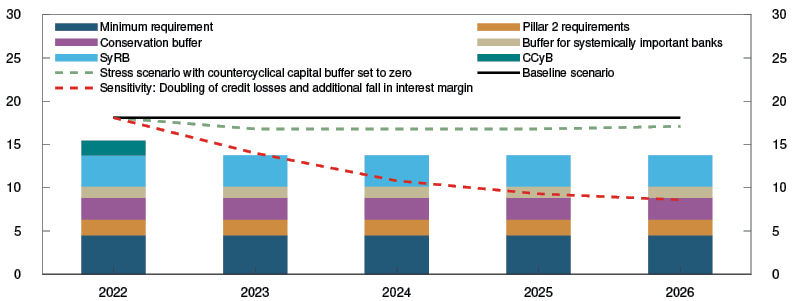

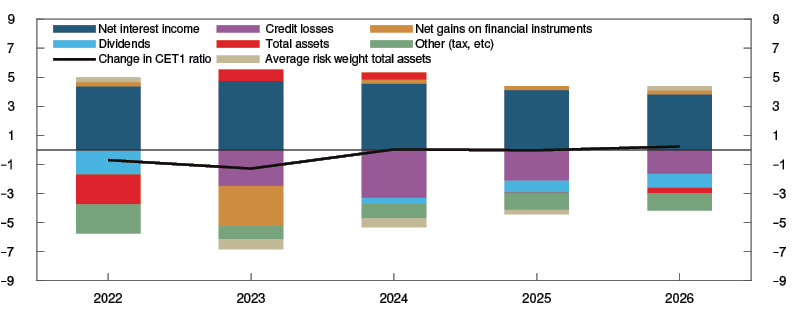

The stress test in this Report shows that the largest Norwegian banks as a whole are capable of absorbing losses in the face of a sharp downturn in an environment where inflation is significantly higher than it is today. In the stress scenario, high living costs and interest rates hit households hard, and banks incur losses. On the other hand, some firms will benefit from high commodity and energy prices. This cushions losses on commercial loans somewhat, but banks still incur significant losses owing to a sharp fall in property prices and belt-tightening by a large number of households. The stress test shows some of the many possible adverse events that the financial system may face and outlines a possible outcome of how the financial system copes with a sharp, but not inconceivable, downturn. The current situation makes it especially important for the financial system to maintain a high level of resilience, so that it can perform its tasks effectively even in the event of severe downturns and economic crises.

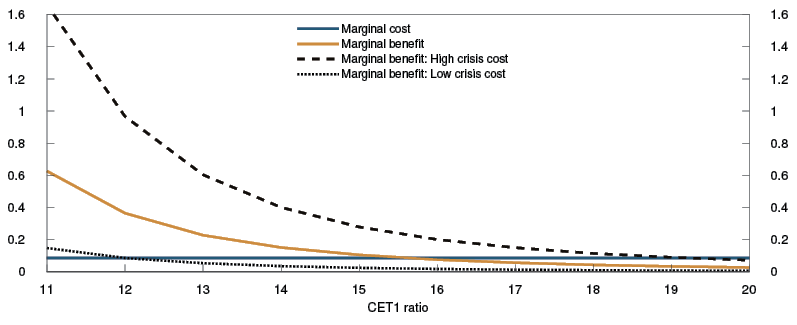

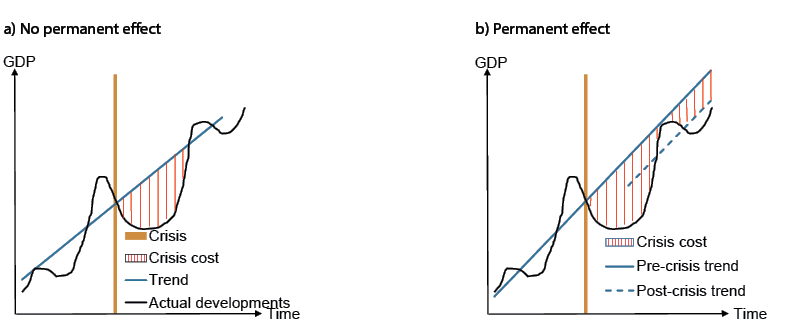

Capital buffers help facilitate bank lending during crises too

Increased bank capital promotes financial stability because it reduces the risk that banks contribute to amplifying a downturn. Sharp economic downturns may result in such large credit losses that banks dip into their capital buffers. Stress tests and sensitivity analyses show that Norwegian banks’ current capital levels are high enough for them to cope with scenarios where losses are considerable. Capital levels are also in line with what analyses show to be the level of capital banks should hold in the long term. Bank capital levels that are too low are more economically costly than if bank capital should prove to be too high.

In 2021, Norges Bank was given responsibility for advising on systemic risk buffer (SyRB) requirement. In June, the Bank published a framework for that advice. The SyRB helps to ensure that banks hold sufficient capital to weather future downturns. Structural vulnerabilities in the Norwegian financial system are broadly at the same level as in 2020, when the SyRB was set at 4.5%. The current level of the SyRB should therefore be maintained.

The countercyclical capital buffer (CCyb) will be set at 2.5% from 31 March 2023. In the aggregate, the buffer requirements help to ensure that Norwegian banks hold sufficient capital.

Ida Wolden Bache

Pål Longva

Øystein Børsum

Ingvild Almås

Jeanette Fjære-Lindkjenn

2 November 2022

1 Vulnerabilities and risks in the financial system

The outlook for financial stability has weakened over the past year. The ongoing war in Ukraine and the after-effects of the Covid-19 pandemic are having substantial economic consequences both in Europe and globally. There is an increased risk of new negative events occurring. A number of the key vulnerabilities in the Norwegian financial system, such as the high indebtedness of many households and banks’ high commercial real estate (CRE) exposures, may amplify a downturn. Many securities prices have fallen so far in 2022 and, after having risen substantially through the pandemic, property prices have fallen this autumn. A digitalised financial system increases vulnerability to cyber attacks, and the threat landscape has become more aggressive over the past year.

Negative events can occur abruptly and come from unexpected sources. Solid profitability, capital adequacy and liquidity ensure that banks are resilient, with ample capacity to absorb loss and deal with market stress. Norges Bank’s Monetary Policy and Financial Stability Committee has decided to advise the Ministry of Finance to maintain the systemic risk buffer (SyRB) rate at 4.5%.

1.1 Heightened geopolitical and economic uncertainty is affecting the financial system

Recent years have been marked by a number of major shocks and negative events, such as the war in Ukraine, the energy crisis, the pandemic, increased inflation and the subsequent global financial volatility with reduced market liquidity. In the current environment of uncertainty regarding the Norwegian and global economy, it is particularly important to maintain the resilience of the financial system. The European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) issued a formal warning to member countries at the end of September, highlighting a number of severe risks to financial stability and stressed the importance of the private sector, market participants and relevant authorities preserving and strengthening resilience (see “European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) warning on vulnerabilities in the financial system”). In its Global Financial Stability Report from October, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) urges policy makers to contain a further build-up of financial vulnerabilities and use macroprudential tools as needed.

High inflation and monetary tightening globally

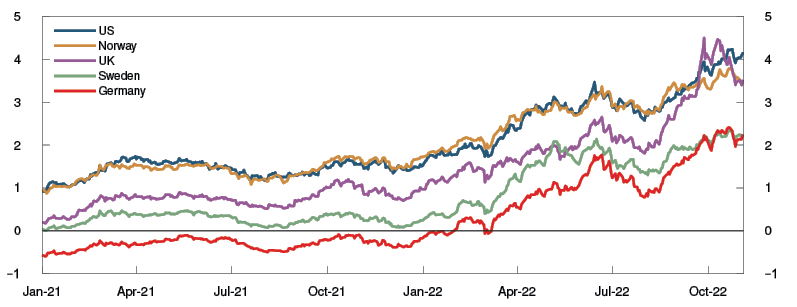

In the years after the financial crisis, global inflation was low in an environment of historically low interest rates in most countries, which contributed to high risk-taking and elevated asset and property prices. Pandemic-related supply and demand conditions and the war in Ukraine have led to a surge in inflation among Norway’s main trading partners since autumn 2021. Reduced Russian gas exports have pushed up energy prices. Energy transitions, such as the phasing out of nuclear power in some countries, have also pushed up energy prices. Faced with higher inflation, central banks have raised policy rates substantially over the past year, and market policy rate expectations indicate further increases in the coming year, both in Europe and the US. Long-term interest rates have also risen considerably over the past year (Chart 1.1).

Chart 1.1 Long-term interest rates have risen considerably over the past year1 Yields on 10-year government bonds in selected countries. Percent

There is a high degree of uncertainty surrounding the outlook for global growth and inflation ahead. The war in Ukraine is impacting both the European and global economy and adding to the uncertainty. For the Norwegian economy, the European market is particularly important. A sharp reduction of Russia’s gas exports to Europe and the risk of energy rationing heightens the risk of a pronounced downturn in the euro area and the UK. In the US, inflation has been high over the past year. In China, pandemic-related restrictions and lower activity in the real estate sector have contributed to weaker growth. If inflation picks up further in advanced economies and monetary policy becomes more contractionary than expected, global economic growth may weaken further and result in further volatility in international financial markets.

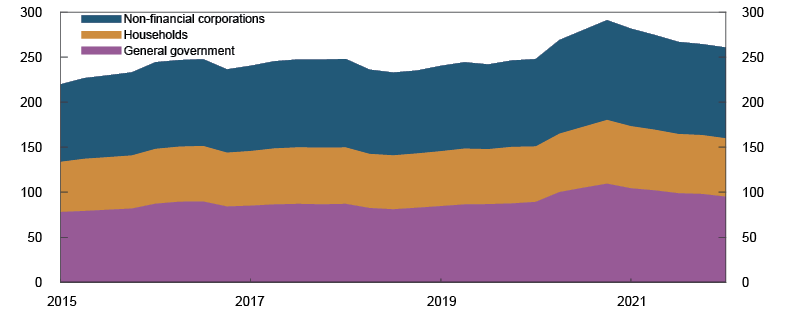

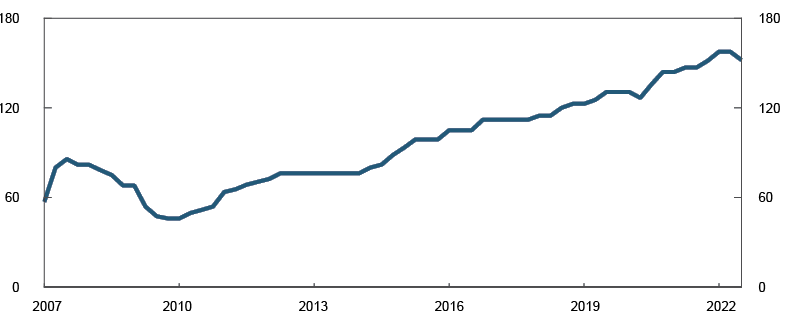

High debt increases the risk that an abrupt and strong tightening of financial conditions will have negative consequences for financial stability. During the period of low interest rates, global debt relative to activity increased, rising further at the beginning of the pandemic owing to both faster debt growth and a sharp fall in GDP (Chart 1.2). In line with higher economic activity, this trend was partially reversed through 2021 and global debt levels were just over 260% at the end of 2021. The increase in global debt was most pronounced in the government sector, reflecting the extensive support measures implemented by many countries during the pandemic. Higher public debt may reduce fiscal space ahead. In addition, higher interest rates will increase interest burdens for many firms, households and governments.

Chart 1.2 General government has increased its share of global debt2 Global non-financial sector debt as share of GDP. Percent

High volatility and lower liquidity in financial markets

The years following the financial crisis were marked by low financial volatility. Low interest rates pushed up property and securities prices. Monetary tightening so far in 2022 has contributed to partially reversing these price increases. Long-term interest rates have risen considerably (Chart 1.1) and bond market risk premiums have also increased.

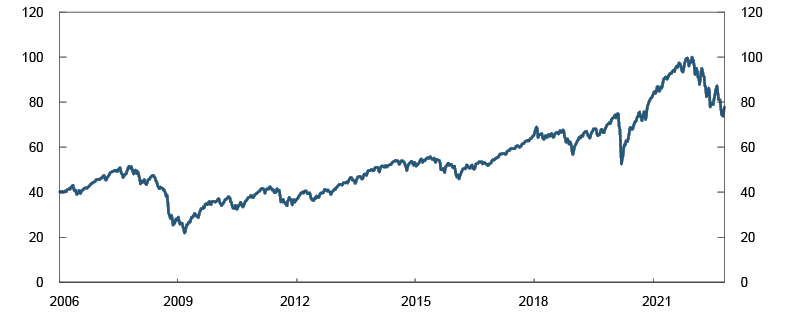

Investors’ required rate of return on financial assets depends on developments in long-term interest rates and risk premiums. In line with the rise in long-term interest rates, yields have increased and equity prices have fallen globally (Chart 1.3). Equities with a high current price-to-earnings ratios, such as technology equities, have fallen substantially. However, there are signs that global equity risk premiums are little changed. Equity prices may therefore be vulnerable to a sudden reductions in investors’ risk-taking. However, bond risk premiums have risen somewhat, particularly in the corporate bond market.

Chart 1.3 International stock indices have fallen considerably this year3 MSCI global stock market index. Week 1 2022 = 100

Uncertainty about the outlook for global growth and inflation has resulted in periods of high financial volatility over the past year, which has contributed to reduced market liquidity. Treasury bond market liquidity in particular has deteriorated, which may also reflect structural conditions4 and balance sheet reductions by some central banks. Prolonged low market liquidity may amplify price movements in periods of market turmoil, which may also reduce access to wholesale funding for governments, banks and firms.

Price volatility has been high in a number of markets. Derivatives contracts often include collateral requirements (margin calls) to reduce counterparty risk. High price volatility has led to a considerable increase in margin calls in a number of markets. During the pandemic, increased margin calls led to periods of liquidity challenges for market participants with large derivatives positions, and in Norway the sharp depreciation of the krone led to liquidity stress for Norwegian asset managers who were forced to fire-sell securities. In 2022, a pronounced rise in energy prices has resulted in liquidity difficulties from time to time for Nordic power producers related to financial derivatives for hedging against energy price changes. High price volatility increased the risk of instability in the Nordic financial system, but government measures to strengthen the liquidity of market participants have improved market functioning. Higher energy prices have not posed any significant problems for Norwegian market participants (see “Challenges in the energy derivatives market”). This autumn, highly volatile UK government bond yields have led to increased margin calls and liquidity problems for a number of UK pension funds (see “Asset managers' behaviour can amplify negative price movements”).

Financial markets are interconnected, and one market participant’s problems can spill over to other participants. The margin call system, which mitigates counterparty risk through collateral agreements, is important for financial stability. At the same time, counterparty margining requirements involve a liquidity risk, and it is important that parties to derivatives contracts take account of this risk.

European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) warning on vulnerabilities in the financial system

On 22 September 2022, the ESRB adopted a warning on vulnerabilities in the EU/EEA to relevant authorities. This is the first time such a joint warning has been issued to all member countries. The role of the ESRB is to monitor the financial system in the EU/EEA and to prevent and mitigate systemic risk. In addition, the ESRB can issue warnings and recommendations. Warnings can be issued when the ESRB identifies financial stability risk.

In its warning, the ESRB notes that a deterioration in economic activity could lead to a further increase in credit risk in financial institutions with weak debt-servicing capacity related to the pandemic. There is still a substantial risk of a sharp fall in asset prices. Weaker household debt-servicing capacity owing to higher borrowing costs and lower real income may trigger a fall in house prices and cyclical risks in real estate markets. The risk of large-scale cyber incidents has also increased. Geopolitical developments since the beginning of 2022 have increased the probability that many of these risks will materialise simultaneously and become mutually reinforcing.

Market participants and authorities need to prepare for the eventuality of a sharp downturn. A resilient financial system is essential for supporting the real economy. Effective collaboration between authorities and prudent risk management practices among market participants are critical for dealing with shocks.

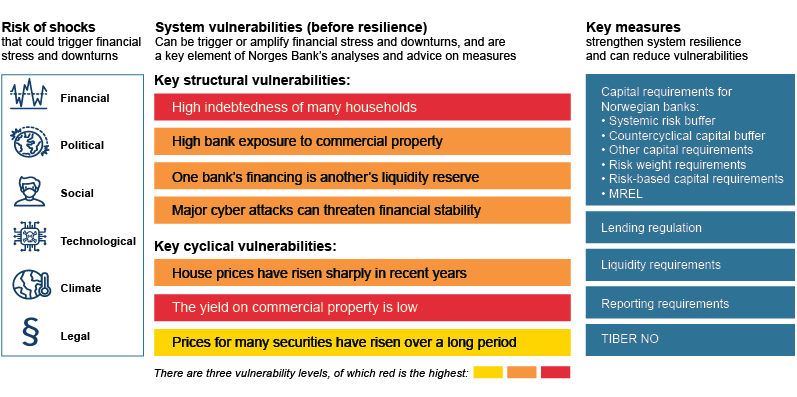

Systemic risks in the Norwegian financial system

Shocks can come from different parts of the economy and financial markets. Negative events related to, for example, technology, climate change and geopolitical and social conditions may also trigger financial crises. Shocks to financial stability are difficult to foresee.

The vulnerability assessment is based on historical experience regarding what causes or amplifies downturns and financial turbulence and on assessments of new features of the financial system. We distinguish between cyclical vulnerabilities, which fluctuate more over time, and structural vulnerabilities, which are longer-lasting. It is difficult to clearly distinguish among vulnerabilities, and vulnerabilities can be mutually reinforcing.

Since the financial crisis in 2008, the Norwegian authorities have introduced a number of rules to mitigate vulnerabilities and increase financial system resilience (see diagram). For more detailed information about these measures, see “Important measures in the financial system in Norway”. The measures primarily help to increase financial system resilience but can also mitigate vulnerabilities. High profitability, sound capital adequacy and sound risk management by financial institutions also strengthen resilience.

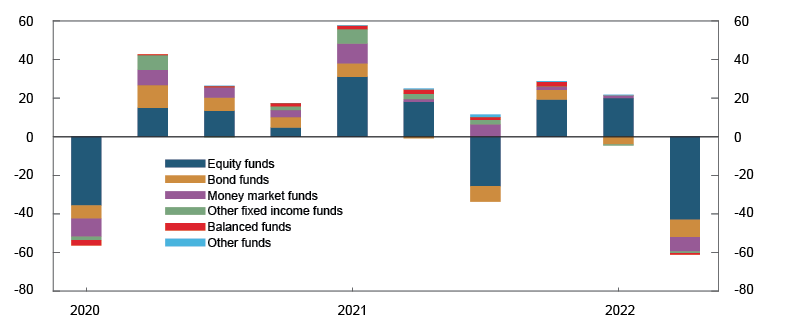

1 Period: 1 January 2021 – 3 November 2022

2 Period: 2015 Q1 – 2022 Q1

Debt in 44 reporting countries, including the euro area.

3 Period: Week 1 2006 – week 44 2022. The index cover equity prices in 2023 advanced economies.

4 See Section 4 in Financial Stability Report 2021 for a discussion of structural conditions that can affect financial market liquidity.

Challenges in the energy derivatives market

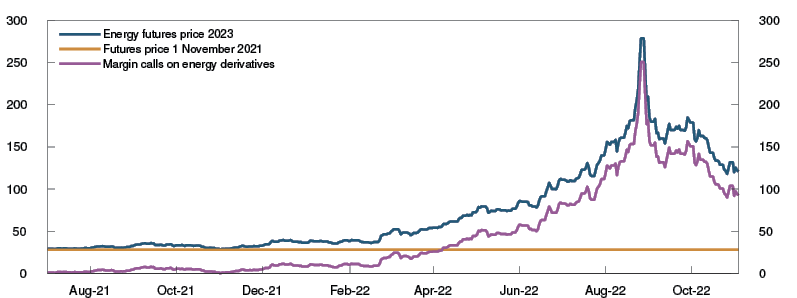

Substantial energy price volatility has given rise to liquidity stress for power producers in the Nordic energy market. Challenges are related to financial derivatives that producers enter into to hedge against changes in energy prices during a specified period.

Financial energy derivatives in Nordic countries are largely settled by the Swedish central counterparty (CCP) Nasdaq Clearing AB (Nasdaq). CCPs guarantee settlement even if one of the parties defaults but also require clearing members to pay initial margin when derivatives contracts are entered into and variation margin when prices change.

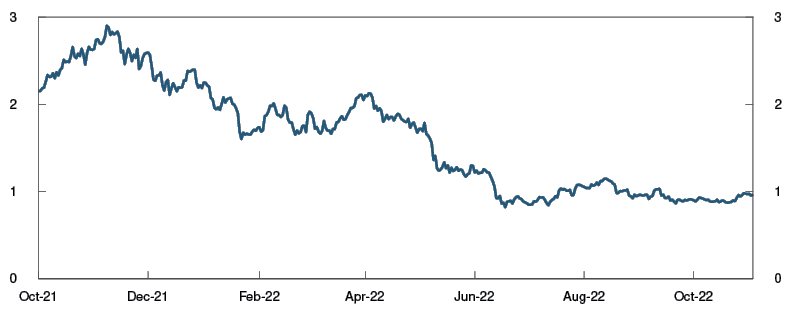

When electricity prices rise, the value of derivatives, such as a futures contract with a delivery price lower than the current price of the contract, becomes negative for parties with a short position in the futures market. When normal price changes occur, this does not entail any particular challenges but at one point, electricity prices in August doubled (Chart 1.A). This resulted in increased margin calls from CCPs. Between June and August, margin calls on Nasdaq increased from SEK 25bn to SEK 180bn.

Chart 1.A Margin calls on energy derivatives have increased significantly System Year-23 contract (ENOFUTBLYR-23) where the variation margin is the future price less the future price at 1. november 2021. Øre/kWh

When margin calls are very high, producers may need loans in an amount exceeding banks’ internal guidelines. Large loans may also bring banks into conflict with rules governing large exposures. In extreme situations, power producers may thus be unable to meet margin calls with liquidity provided by their bank. In Norway, a large number of power producers are publicly owned, with hydropower generation providing a steady revenue stream at low cost. It therefore appears unlikely that Norwegian power producers would not be able to borrow from financial institutions or markets to cover a temporary liquidity shortfall.

At the beginning of September, the Swedish authorities guaranteed SEK 250bn for Nasdaq clearing members. The guarantee was intended to counter the risk of financial instability in the Nordic countries and enables banks to lend to power producers without risk. Nor are government-guaranteed loans subject to the rules governing large exposures. The European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) has proposed allowing a wider range of securities to be used to meet margin calls on energy derivatives. This expansion permits the use of bank guarantees and public guarantees as collateral and is intended to ease liquidity pressures on non-financial market participants.

The CCP Nasdaq is used by power producers across the Nordic countries. Norwegian producers also enter into a substantial number of contracts outside of Nasdaq in what are called bilateral trades. Requirements for margins in bilateral contracts are typically less stringent than for centrally cleared contracts. These contracts are settled between parties that agree any collateral requirements themselves. Higher energy prices have therefore not led to any appreciable liquidity problems for Norwegian power producers. Under bilateral settlement, parties to a contract must bear their own losses if the counterparty defaults. However, creditworthy parties may judge that the potential credit risk is smaller than the costs involved in posting margin to a CCP.

Concepts in derivatives markets

Derivatives

Contracts where the value is related to or derived from an underlying asset (electricity, gas, equity, bond, foreign exchange, interest rate etc). Derivatives can be used to reduce or increase exposure to an underlying asset and are therefore useful in managing risk. A derivatives contract may entail a physical delivery, which means that counterparties must deliver and settle at an agreed price or agree on cash settlement at maturity. The latter are known as financial derivatives.

Variation margin

Amounts that reflect the size of exposure given the most recent prices (value of the contract). Over the tenor of the derivative, the counterparty with a derivatives position with a negative market value must post variation margin while the counterparty with a positive position receives the variation margin. If the trade is centrally cleared, the margin call will be made by the central counterparty, which normally forwards the payment to the counterparty that is owed money. If the contract is settled bilaterally, variation margin is settled between the counterparties directly.

Initial margin

Amounts (cash and securities) that are collected and are intended to cover potential changes in the value of a counterparty’s position from the time the counterparty is in default until the position can be closed. Initial margin is typically posted when contracts are entered into, but in the event of large price movements, increased initial margin may be called over the tenor of the derivative. Initial margin is posted for centrally cleared derivatives but are less common in bilateral derivatives contracts. In contrast to variation margin, initial margin is paid by both counterparties to a derivatives contract and is held by the central counterparty until the contract matures.

1.2 Financial system vulnerabilities

Vulnerabilities in the Norwegian financial system can amplify the impact of shocks on financial stability. High household debt levels, banks’ large exposure to commercial real estate (CRE) and the fact that one bank’s funding is another bank’s liquidity reserves are key structural vulnerabilities, as are major cyber attacks. In Norges Bank’s assessment, structural vulnerabilities are at approximately the same level as in 2021.

Debt growth and asset price inflation have often been high prior to financial crises and are indicators of cyclical vulnerabilities. Many securities prices have fallen so far in 2022 and, after having risen substantially through the pandemic, property prices have fallen this autumn. In Norges Bank’s overall assessment, cyclical vulnerabilities are approximately unchanged over the past year.

Many households are highly indebted

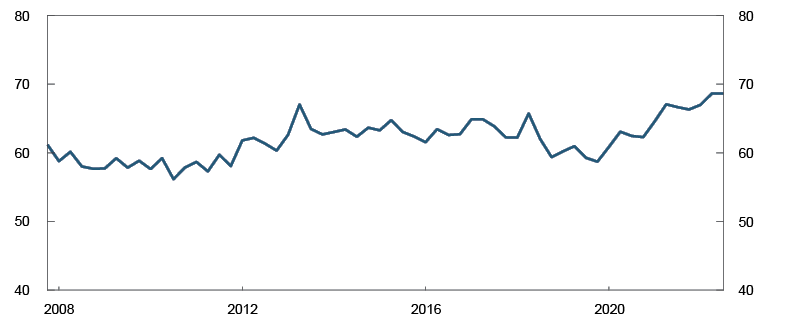

The high debt of many households is the main structural vulnerability in the Norwegian financial system. Household leverage is close to a historically high level (Chart 1.4) and is high compared with other countries. High income growth, especially in the form of increased equity dividends5, contributed to the decline in household leverage towards the end of 2021. High household debt in Norway largely reflects elevated house prices and a large proportion of home ownership. In addition, residential mortgage rates have been very low over several years, which has pushed up debt levels and house prices. Household debt is unevenly distributed, and household leverage is particularly high among younger age groups, as many first-time home buyers and households trade up in the housing market (Chart 1.5). During the period between 2010 and 2020, household leverage increased across all age groups. Data from Finanstilsynet’s (Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway) residential mortgage lending survey for 2022 shows that almost half of all new loan amounts have been granted to borrowers with debt over four times annual income. This share was unchanged from 2021 and slightly higher than in 2020.

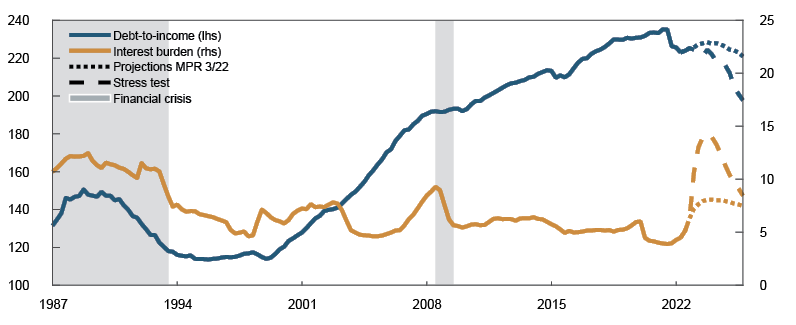

Chart 1.4 Household leverage is high and interest burden is increasing6 Percent

Chart 1.5 The debt burden has increased across all age groups7 Percent

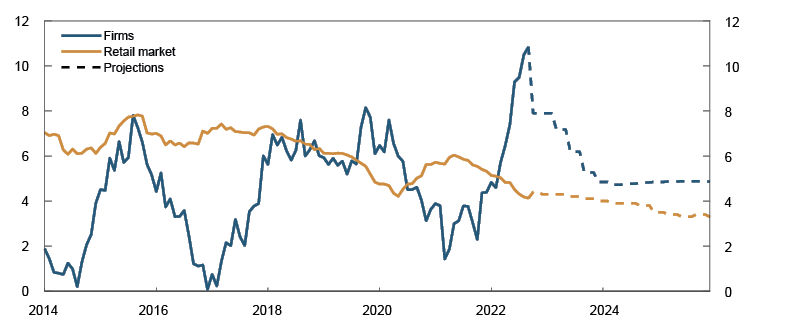

Households’ interest burden, ie the ratio of income to interest payments, fell to a historically low level during the pandemic. More than 90% of households have floating-rate loans, and the interest burden will rise ahead in pace with higher lending rates. Household debt service ratios, which also include estimated principal payments, are expected to rise owing to higher interest rates and a high level of household debt. In Norges Bank’s Survey of Bank Lending 3/2022, banks report slightly lower household credit demand in 2022 Q3, and several banks reported an increase in demand for interest-only loans. Lending standards were overall unchanged in 2022 Q3, and the banks expect a slight tightening of lending conditions in 2022 Q4. Over the next few years, with debt growth expected to be somewhat lower than income growth, household leverage will decline (see Monetary Policy Report 3/22 and Chart 3.1 in the stress test in Section 3). This may, over the longer run, help reduce the vulnerabilities associated with high household debt. However, there is considerable uncertainty surrounding economic developments ahead.

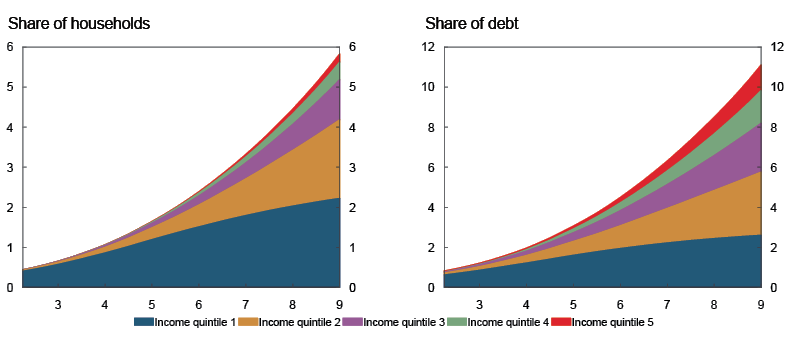

High debt makes households vulnerable to income loss, higher interest rates or a decline in house prices. In addition to increased interest expenses, households are facing higher expenses related to, for example, food and electricity. However, a sensitivity analysis shows that most households are able to service their debt. Only between 2% and 3% of homeowner debt is held by households who may have difficulties covering normal expenses and expected higher interest rates with disposable income and assets, compared with about 1% at 2020 price- and interest rate level (see “Households are resilient to moderate increases in interest rates and other expenses”). Low-income households account for a large share of households with payment problems, but a larger share will have to tighten consumption, which may amplify an economic slowdown.8 Analyses9 also show that much of the highly vulnerable consumer debt is held by low-income and non-homeowners. At the same time, this accounts for a small share of total debt. Bank losses are expected to remain low ahead (see Section 2), but losses on loans to customers with weak debt-servicing capacity will likely edge up.

Considerable uncertainty about the macroeconomic outlook ahead entails heightened risk of new negative events, and highly indebted households may be particularly vulnerable. A sensitivity analysis (see “Households are resilient to moderate increases in interest rates and other expenses”) shows that in a scenario with, for example, high interest rates and a sharp fall in house prices, many households may have difficulties covering normal expenses and interest. Banks’ losses may then rise owing to households defaulting on their debt. The analysis illustrates that many households in such a situation may have to reduce consumption to a relatively moderate level. This may pose a threat to financial stability because a tightening of consumption may reduce firms’ earnings and thus their debt-servicing capacity. The stress test in Section 3 illustrates this scenario.

Commercial property prices could fall sharply and lead to substantial bank losses

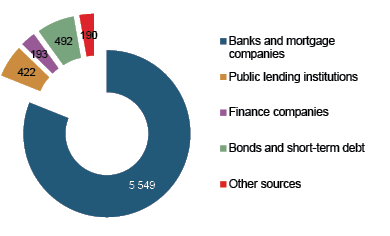

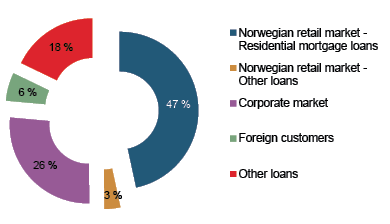

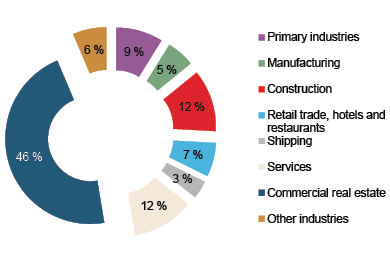

Banks’ high CRE exposures are a key structural vulnerability, at the same time as low yields are a cyclical vulnerability that increases the risk of a sharp fall in commercial property prices. Banks’ CRE lending is substantial and accounts for around half of total corporate lending (Annex Chart 4). A large share of banks’ exposures is concentrated in a few banks. Four banks account for about two thirds of total commercial real estate loans. Experiences of banking crises in Norway and abroad have shown that losses on CRE exposures have been an important factor behind solvency problems in the banking sector.

Developments in rental income are important for CRE firms’ debt-servicing capacity. Rental income in the period ahead is secured by existing leases, provided tenants are able to pay rent. Existing leases are normally linked to consumer price inflation, which in isolation helps strengthen CRE firms’ debt-servicing capacity in periods of high inflation. A sharp fall in commercial property prices may strongly impair CRE firms’ solvency. If a fall in prices leads to the properties’ mortgage value becoming lower than the value of the loans, banks may incur losses upon default of the debt. However, the rise in CRE prices since the financial crisis has not been matched by corresponding borrowing. This has boosted CRE firms’ equity ratios, strengthening resilience to price falls.

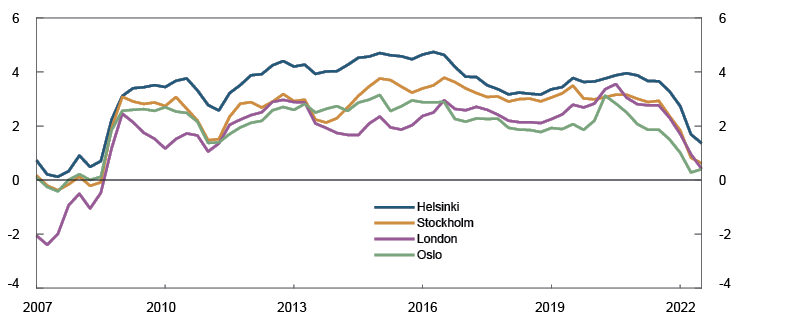

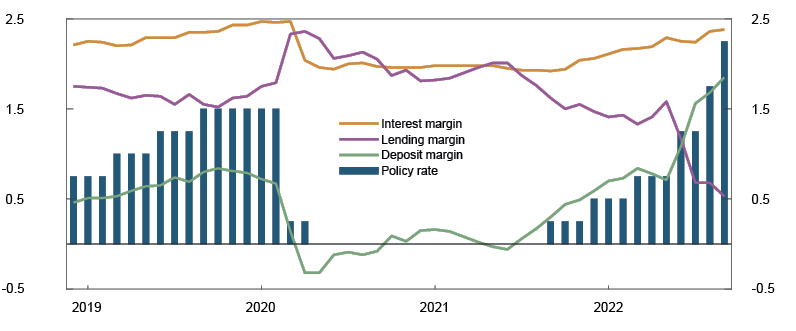

Commercial property prices in Norway and in other countries have risen substantially in recent years and prices in Oslo rose markedly through the pandemic (Chart 1.6). Selling prices are calculated as rents divided by yield. The rise in selling prices reflects both higher rents and a lower yield. Over the past year, selling prices have been driven up by a substantial rise in rents.

Chart 1.6 Commercial property prices have edged down this autumn10 Estimated selling prices for prime office space in Oslo. In thousands of NOK per square metre

In 2022 Q3, the yield rose sharply, and rents increased markedly according to Norges Bank’s price statistics. Overall, selling prices fell somewhat. Because recent transactions have been at a low ebb, there is considerable uncertainty surrounding actual market prices. Over the past half year, real estate portfolio writedowns of major market participants and surveys11 of property investors show that the yield in most CRE segments have risen recently in Norwegian cities.

The yield depends on developments in long-term interest rates and risk premiums. The spread between the yield and the five-year swap rate, which is a simple measure of the risk premium, is at a low level (Chart 1.7). This applies both in Oslo and other European cities. In the years ahead, a gradual rise in the yield for Oslo and a moderate rise in rents are expected. Overall, the projections for rents and the yield indicate that selling prices will fall in the years ahead (see Monetary Policy Report 3/22).

Chart 1.7 The difference between yield and long-term interest rates is at a low level12 Yield less five-year swap rate. Percentage points

Low yields increase the risk of a sharp fall in commercial property prices. New periods of substantial market volatility may lead to a higher risk premium and higher yields than previously assumed. Higher long-term interest rates will also pull up the yield. In the event of a more pronounced slowdown than currently envisaged, developments in rents may be weak. A sudden increase in the yield and a fall in rents will entail a sharp fall in selling prices. If commercial property prices fall in line with the projections, banks’ CRE loan losses are expected to remain low. However, in a downturn where commercial property prices fall sharply, banks’ CRE loan losses may be substantial (see the stress test in Section 3).

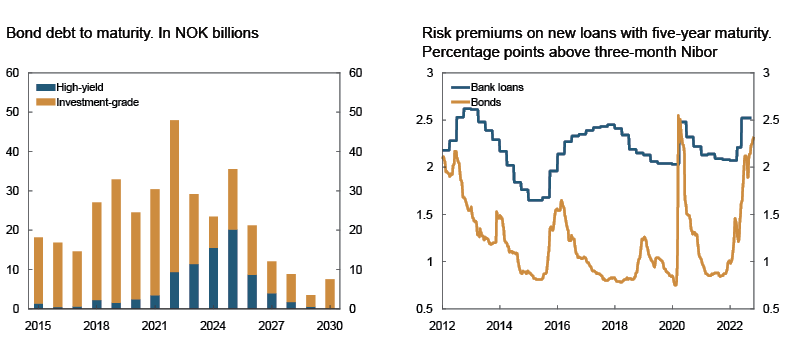

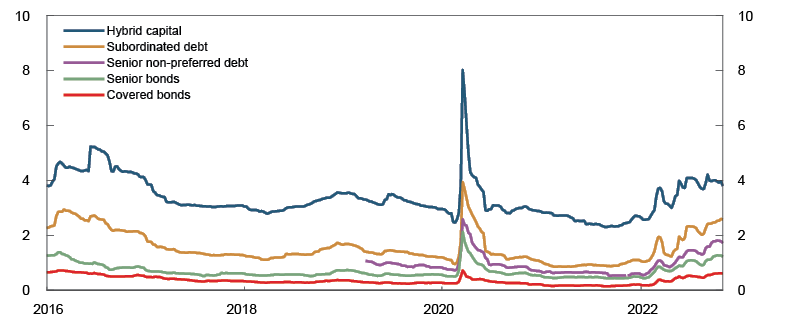

Over the past year, CRE firms’ financing costs have increased owing to the higher interest rates and credit premiums. The debt-to-revenue ratios of CRE firms is higher than that of other firms and their profitability is more vulnerable to higher interest expenses compared with firms in other sectors. Bank debt accounts for the largest share of CRE firms’ debt, but bond debt is an increasingly important source of financing. Bond market and bank lending premiums have increased substantially (Chart 1.8). A majority of the banks in Norges Bank’s lending survey in October report that, owing to developments over the past year, they require stricter debt-servicing capacity and equity ratio requirements for new CRE loans. A large amount of bond debt issued by CRE firms will mature in the years ahead. A marked fall in commercial property prices may lead to some CRE firms finding it difficult to issue new bonds at the same time as obtaining bank loans may be more challenging.

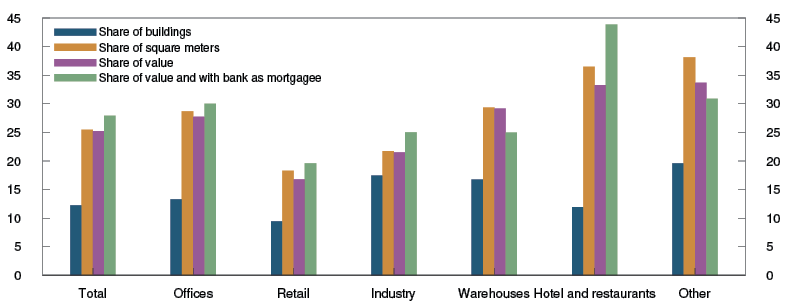

Chart 1.8 Higher premiums increase refinancing costs13

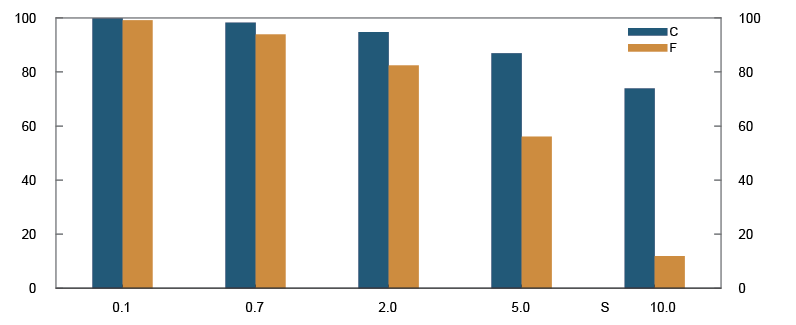

The CRE market is heterogenous, where office buildings are by far the largest segment. An analysis14 by Norges Bank indicates that banks are broadly exposed to various categories of commercial property. Office premises in the largest cities account for the largest share of commercial property value in Norway, and banks have considerable exposures to this segment (Chart 1.9). Banks also have large exposures to retail and industrial buildings and exposure to warehouse/logistics properties is also substantial, while banks are markedly less exposed to hotels and restaurants. Banks’ diversification across various segments in isolation reduces the risk of losses on banks’ CRE exposures.

Commercial buildings by segment. Percent Chart 1.9 Banks’ exposures reflect market composition15

The climate transition may result in structural changes in the CRE market. Norges Bank’s analyses show that the usage costs of buildings with low energy-efficiency may increase considerably in the event of high electricity prices over time, which in turn could weaken the rents of such buildings (see “Growing importance of energy-efficient buildings in the years ahead”). The effect on rents in such a situation is very uncertain, and the impact on rents can be mitigated by energy efficiency measures. The analysis also shows that less than 25% of commercial buildings in Norway have a registered energy label, and among these fewer than half have a high energy label rating. Office buildings have the highest share of buildings with an energy label rating, and bank exposure to this segment is particularly high. Norway does not yet have a system in place to classify Norwegian buildings according to the EU green taxonomy, which will enter into force in Norwegian law in 2023. Inadequate reporting according to the taxonomy can have consequences for the ability of Norwegian banks to issue “green loans”, and thus the possibility to raise “green funding” with lower credit premiums.

One bank’s funding is another bank’s liquidity reserves

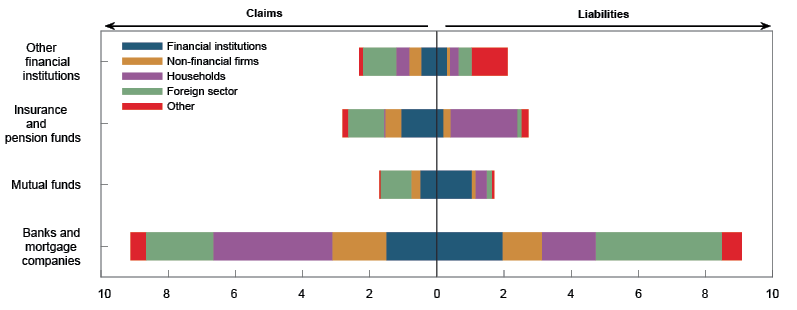

Banks are interconnected through interbank exposures and common or similar securities portfolios, often traded in the same markets. Close interconnectedness means that problems in one bank can easily spill over to other banks. At the same time, a high level of interbank cooperation in the money market is important for promoting the efficient distribution of liquidity and the transmission of monetary policy. Banks also have an important role to play as intermediaries in financial markets, where they contribute to maintaining liquidity (see also Section 2).

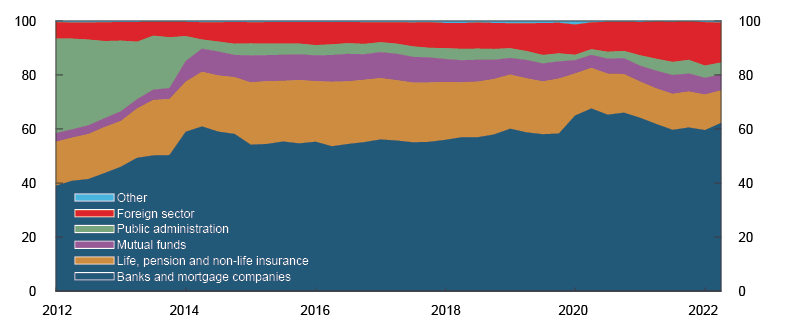

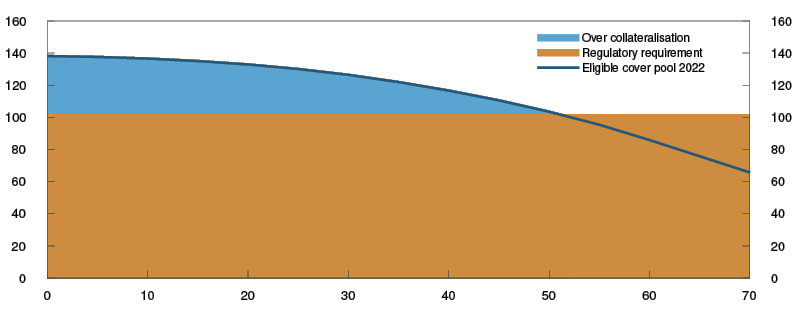

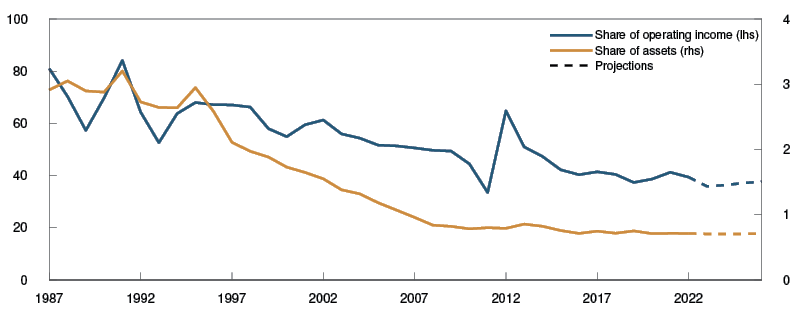

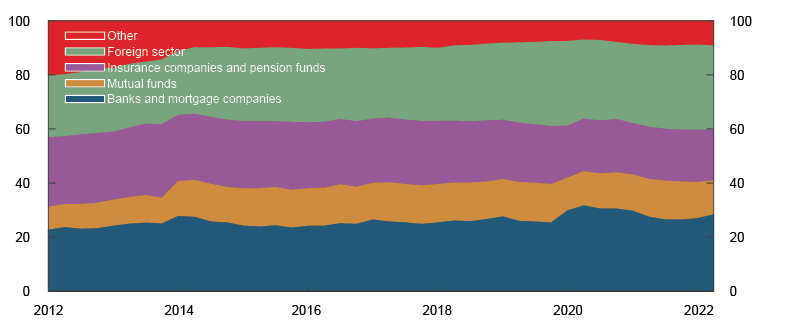

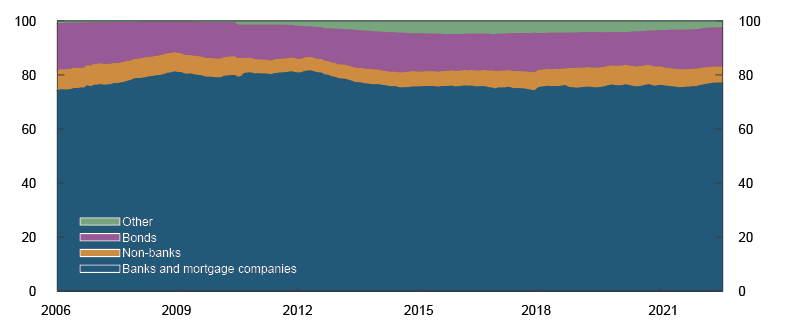

Norwegian interbank exposure has accounted for about 6% of bank balance sheets in recent years. More than half of this exposure is through the covered bond market, and in total banks hold approximately 60% of other Norwegian banks’ covered bonds issued in NOK (Chart 1.10). Banks’ share of covered bond holdings, both as a share of balance sheets and the volume outstanding in the market, has risen since the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) requirement was introduced at the end of 2015. The high ownership share is likely attributable to the fact that covered bonds are the largest type of securities in the Norwegian market that can be used to both satisfy liquidity requirements and as collateral for loans from Norges Bank.

Chart 1.10 Banks hold the majority of covered bonds16 Ownership composition for bonds issued by Norwegian mortgage companies in NOK. Percent

Covered bonds are also an important source of funding and account for two thirds of banks’ and mortgage companies’ bond funding. About half of covered bond funding is issued in NOK. Banks therefore act both as issuer and investor in this market.

The purpose of owning liquid securities is to enable banks to sell or pledge these securities if they have difficulty in obtaining new funding. If there are simultaneous fire sales of covered bonds by a number of banks, prices may fall sharply. This will reduce the value of banks’ liquidity portfolios, making them less able to withstand liquidity problems. Since a number of banks hold the same or similar securities, the fall in value owing to fire sales can be a source of losses across the financial system.17 The cover pool for covered bonds largely comprises collateralised residential mortgage loans and a concurrent pronounced fall in house prices can further exacerbate funding problems and amplify the sell-off of covered bonds (see Section 2).

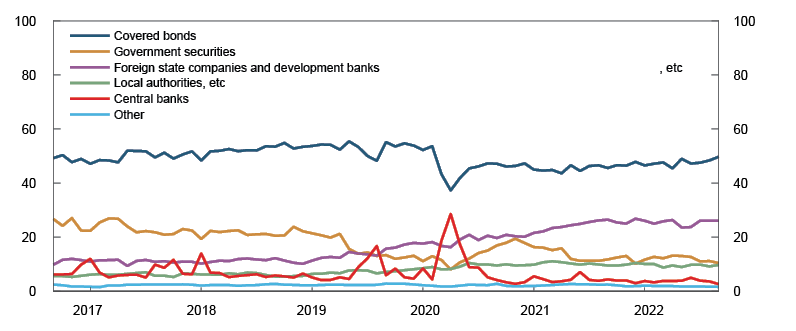

In recent years, the composition of Norwegian banks’ liquidity reserves in NOK has changed somewhat. The share of covered bonds in the liquidity reserves has fallen from about 55% to slightly less than 50% (Chart 1.11). The fall in the share of covered bonds has been matched by a higher share of securities issued in NOK by multilateral development banks and foreign public companies and local governments.

Chart 1.11 Covered bonds as a share of banks’ liquidity portfolios has fallen somewhat18 Liquidity portfolio in NOK by asset type. Norwegian banks and mortgage companies. Values after haircut. Percent

A diversified liquidity portfolio helps banks to spread divestments over several types of securities, which contributes to reducing vulnerabilities associated with interbank exposures. At the same time, banks’ share of covered bond holdings are little changed in recent years.

House prices have risen substantially in recent years, but have now started to fall

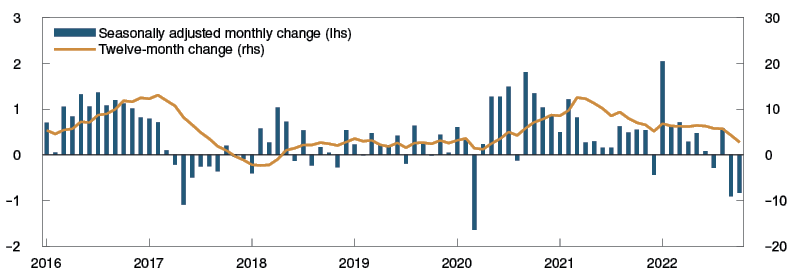

House prices have long risen faster than income. Through the pandemic, house prices rose substantially owing to low interest rates and limited consumption opportunities (Chart 1.12).

Chart 1.12 House prices have risen substantially in recent years, but have now begun to fall19 Percent

House prices fell in autumn, after rising rapidly at the beginning of 2022. The fall has been somewhat more pronounced than projected. Many existing dwellings put on the market and lower sales have led to a strong rise in the number of unsold dwellings. House prices are expected to continue to decline in the period to autumn 2023, primarily owing to higher lending rates (see Monetary Policy Report 3/22). After a period of very low lending rates and high household debt ratios, it is uncertain how households will react to substantial increases in prices and interest rates. For example, household demand for housing may be more sensitive to interest rate increases than assumed in our projections. Changes in house price expectations may also result in a sharper fall in house prices than projected, for example if many households bring forward home sales and postpone home purchases. Large declines in house prices may contribute to a sharp tightening of household consumption and substantial bank losses (see Section 3.1). There have, however, been very few periods of sharply falling house prices in Norway since the mid-1900s (see “Few periods of a steep fall in house prices in Norway”).

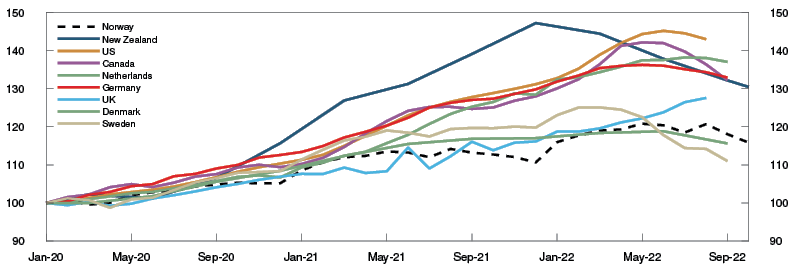

House prices in many countries rose considerably faster than in Norway during the pandemic (Chart 1.13). Recently, house prices have declined in a number of countries. The decline has been particularly pronounced in New Zealand and Sweden, where prices have fallen by around 10% since the price peak. Since the beginning of 2020, house prices overall have nevertheless risen by more than 30% in the US, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Canada and Germany. In the same period, house prices in Norway have risen by around 15%.

Chart 1.13 House prices have recently fallen in many countries20 Index. January 2020 = 100

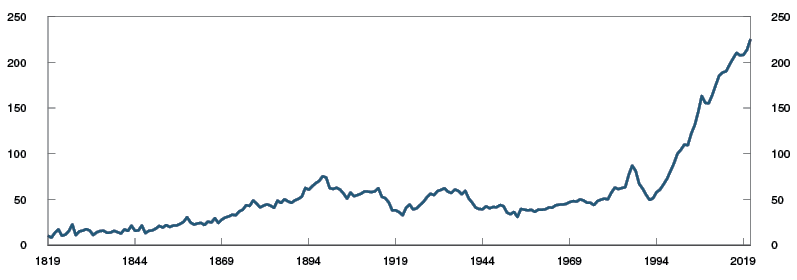

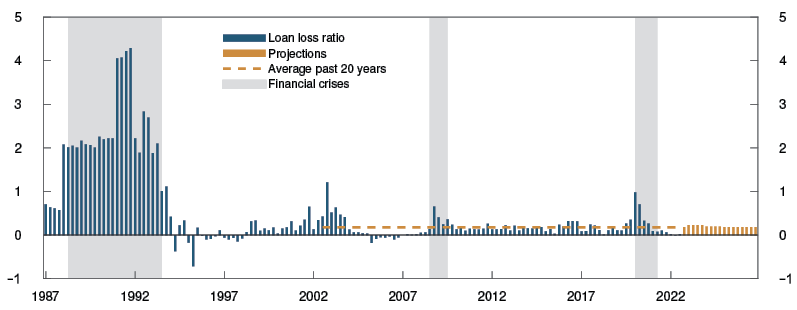

Few periods of a steep fall in house prices in Norway

House prices in Norway have risen sharply in recent decades (Chart 1.B). Historically, real house prices, ie house prices relative to inflation, have rarely fallen. Prior to the Second World War, there were four periods of a substantial fall in real house prices. Three of these periods occurred in the first half of the 1900s, and as a result, real house prices through almost all of the 1900s were lower than at the end of the 1800s.

Chart 1.B Few periods of a steep fall in house prices over the past 200 years1 Real house prices. Index. 2000 = 100

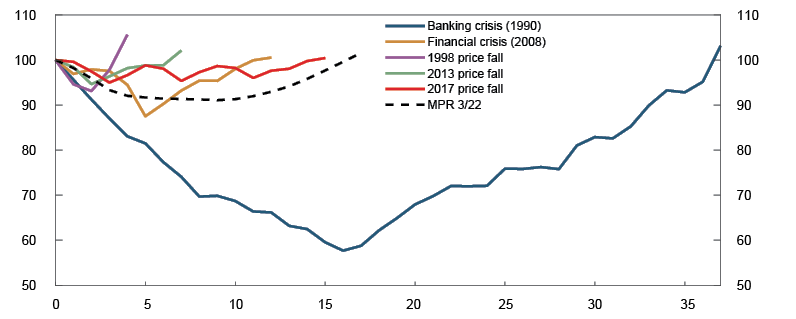

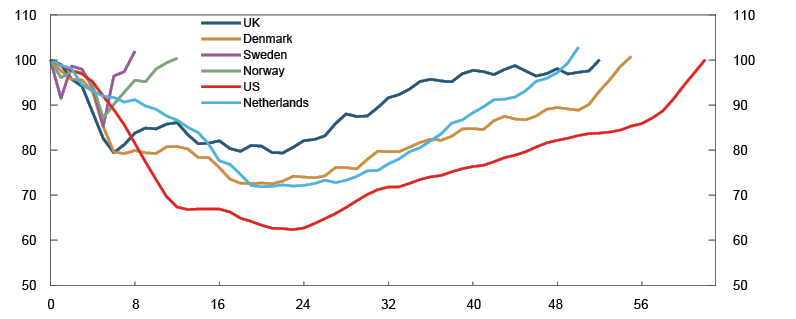

Since the Second World War, the only steep fall in real house prices occurred during the banking crisis. Between 1988 and 1992, real house prices fell by just over 40% from peak to trough, and it took more than five years for real house prices to return to their pre-1988 levels (Chart 1.C). The second steepest fall in house prices in Norway over the past 50 years took place during the financial crisis, when real house prices fell by 12% from peak to trough. However, it took less than two years before prices returned to their pre-crisis peak. Many other countries experienced a steeper fall in house prices during the financial crisis. In the US, the fall in house prices overall was approximately the same as during the banking crisis in Norway, but house prices also fell sharply in Denmark, the Netherlands and the UK, for example (Chart 1.D).

Chart 1.C Few house price falls in Norway in the last decades2 Real house prices. Seasonally adjusted. Quarter before price fall = 100. Quarters since start of price fall

Chart 1.D Steeper falls in other countries during the financial crisis3 Real house prices. Unadjusted. Quarter before price fall = 100. Quarters since start of price fall

Since the financial crisis, Norway has experienced two minor house price declines, in 2013 and 2017, respectively. The projections in Monetary Policy Report 3/22 suggest that real house prices will fall by 9% over the coming year. This is slightly less pronounced than the fall observed during the financial crisis in Norway, but it is expected that it will take somewhat longer for house prices to recover. The projections are uncertain, however.

1 Period: 1819 - 2021.

House prices adjusted for Consumer Price Index (CPI).

2 Nominal house prices adjusted by consumer price index adjusted for tax changes and excluding energy products (CPI-ATE).

3 Indexed to 2007 Q3 for Norway, Sweden, Denmark and the UK, 2006 Q1 for the US and 2008 Q3 for the Netherlands. Nominal house prices adjusted for CPI excluding food and energy prices.

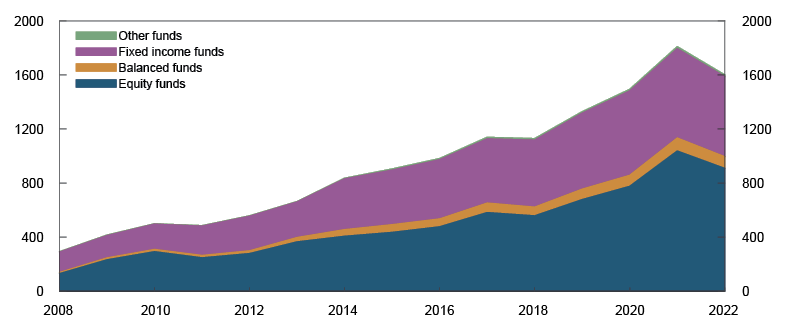

The prices of many securities have risen over a long period but have reversed course

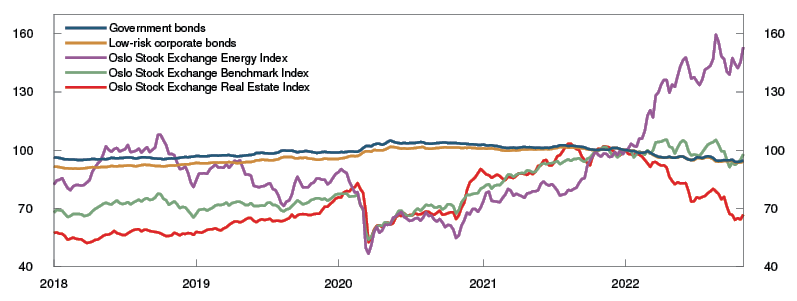

During the pandemic, securities prices have risen sharply. The rapid rise has largely been driven by lower returns, which in turn reflect the very low long-term interest rates in many countries. Over the past year, long-term interest rates have moved up, and securities prices globally and in Norway have fallen. At the same time, there is considerable geopolitical uncertainty, and the outlook for growth and inflation is uncertain. This increases the risk of negative events that can lead to further financial market volatility and higher required rates of return.

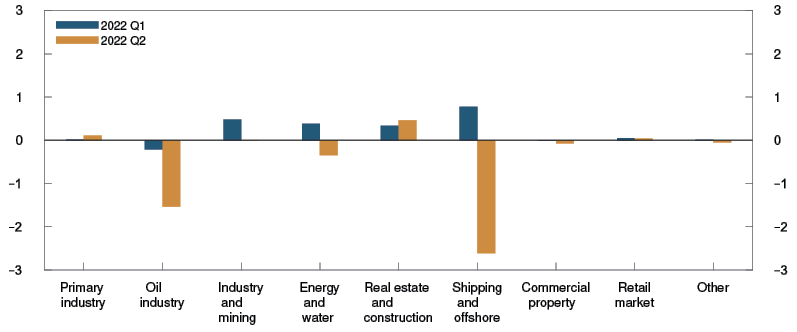

Price volatility has been high in the equity and bond market in Norway in 2022 (Chart 1.14). In terms of the Oslo Børs Benchmark Index, the value of Norwegian equities overall has remained broadly unchanged this year. However, there are considerable differences in price performance across sectors. In some sectors, such as oil and gas, earnings growth has been strong and prices have risen considerably. In many other sectors, such as real estate, prices have fallen sharply in 2022. Compounded indexes for Norwegian bonds show a price fall of around 6%. The fall in prices has been driven by both higher interest rates and higher credit premiums. The increase in premiums coincides with low issue activity in the corporate bond market and a rapid rise in bank lending.

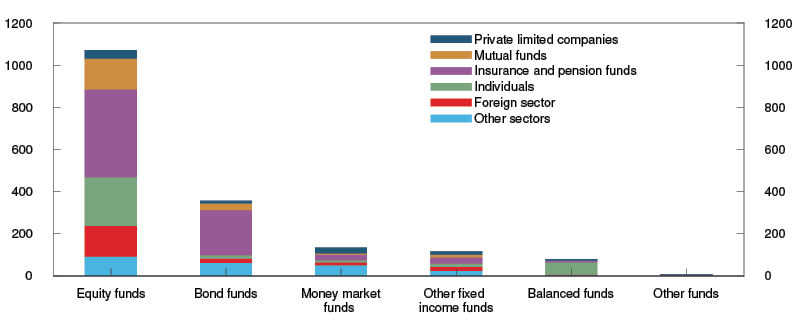

Chart 1.14 Securities prices have been volatile and have fallen somewhat this year21 Compound indexes for different kinds of securities. Index. Week 1 2022 = 100

Sharp falls in securities prices can weaken financial stability through a number of channels. Sharp falls in securities prices may impair banks’ access to wholesale funding and reduce the value of their securities holdings. Liquidity and capital regulation strengthen banks’ resilience to periods of market stress, but banks are nonetheless vulnerable to a prolonged dry-up of wholesale funding. Reduced access to wholesale funding will also affect firms that obtain financing directly in the bond market. A steep and abrupt fall in securities prices may increase the risk of fire sales of securities by financial institutions (see Section 2.4), which may amplify market stress. Many households hold equities and bonds, even though housing and other real estate account for most of household wealth. Many households have increased their financial assets through the pandemic and have increased their exposure to equity markets when transitioning from a defined-benefit to defined-contribution pension scheme (see Section 2.4). This increases the risk that a fall in securities prices will contribute to tightening consumption and reducing corporate earnings.

5 Dividend tax was increased from 31.7% in 2021 to 35.2% in 2022, which explains the jump in dividend income in 2021.

6 Period: 1983 Q1 – 2022 Q2. Debt-to-income ratio is loan debt as a percentage of disposable income. Disposable income is income after taxes and interest payments. Debt service ratio is interest and estimated principal payments as a percentage of after-tax income. Interest burden is interest payments as a percentage of after-tax income.

7 Period: 2010–2020.

Debt as a share of disposible income. By age of the household’s main income earner.

8 See discussion in Monetary Policy Report 3/22 for estimated consumption and box on page 38 in Monetary Policy Report 2/22 on the estimated effect of higher interest rates and consumer prices facing households.

9 See Lindquist, K.-G., H. Solheim and B.H. Vatne (2022) “Personer med lav inntekt og uten bolig holder mest av særlig utsatt forbruksgjeld” [Low income, non-homeowners hold the largest share of the most vulnerable consumer loans]. Blog post published on the Bankplassen blog on 17 August 2022. Norges Bank (in Norwegian only).

10 Period: 2007 Q1 – 2022 Q3

11 See Malling og Co (2022) “Yield- og sentimentundersøkelse Q3 2022” [Yield and sentiment survey 2022 Q3] (in Norwegian only).

12 Period: 2007 Q1 – 2022 Q3. Prime office space.

13 Period: 2015–2030

Period: Bank loans: 2012 Q1 – 2022 Q3. Bonds: Week 1 2012 – Week 44 2022

The margin for bank loans is for a loan on centrally located office space in Oslo as colleteral, an LTV of 65% and average remaining lease term of 7 years. Bond premiums are for investment grade firms.

14 See Bjørland, C., I.N. Hjelseth, J.H. Mulelid, H. Solheim and B.H. Vatne: “Næringseiendomsmarkedet – ikke lenger en ‘svart boks’”, [The CRE market – no longer a “black box”] (in Norwegian only, forthcoming in English). Staff Memo 6/2022. Norges Bank.

15 At 30 June 2022

16 Period: 2012 Q1 – 2022 Q2

17 See box on page 45 of Financial Stability Report 2019.

18 Period: September 2016 – September 2022

19 Period: January 2016 – October 2022.

20 Period: January 2020 – October 2022.

Linear interpolation of quarterly data for Denmark and New Zealand. Data including August 2022 for the UK and the US and data including September 2022 for Sweden, the Netherlands, Germany, Canada and Denmark. For Denmark, the data only cover detached houses. The Canada index is a weighted average of eleven metropolitan areas.

21 Period: Week 1 2018 – week 44 2022.

1.3 Cyber attacks are a potential threat to financial stability

The number of cyber attacks on the financial sector has increased in recent years. So far, cyber attacks have not given rise to financial crises in Norway or globally, but the increased number of serious incidents, such as the Colonial Pipeline attack, illustrates the potential for attacks to have systemic consequences if they impact critical parts of the financial system. In serious cases, attacks against individual institutions can also have consequences for the system as a whole. This suggests a need for strengthened resilience to cyber attacks at both individual entity level and systemic level.

A digitalised financial system increases vulnerability to cyber attacks

The Norwegian financial system is highly digitalised, which makes it cost-efficient, highly flexible and user-friendly but also vulnerable to cyber attacks. Interconnectedness and concentration in the financial system can further amplify and propagate the consequences of a cyber attack, particularly if attacks impact critical infrastructure, key ICT providers or widely used software. If an attack disables critical functions or if institutions not directly impacted experience liquidity problems, financial stability may be threatened. This applies especially if confidence in the financial system weakens.

System vulnerabilities depend on how well individual institutions are able to reduce their own operational risk. Greater specialisation and a high degree of outsourcing of ICT services result in longer and more complex supply chains. This makes it more difficult to monitor and manage cyber risk, which is also compounded by the recruitment difficulties in this field. According to Finanstilsynet’s assessment, the risk associated with firms’ cyber defences and contractor management has increased somewhat since 2021.22

Norges Bank has previously pointed out that critical functions in the financial infrastructure are dependent on a handful of key ICT providers. Greater use of cloud services increases concentration. Large ICT providers have more resources and expertise for strengthening the cyber resilience of their solutions than smaller providers. At the same time, increased concentration and more dependencies will amplify the impact of a successful attack. The forthcoming European Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA) will likely enter into force in the EU in 2023 and authorise the supervision of systemically important financial sector service providers.

The threat landscape has become more difficult to gauge

The financial sector manages substantial assets, making it a particularly attractive target for organised crime. It also manages a considerable amount of sensitive information, and participants in the system operate critical infrastructure. This makes the financial system a potential target for state actors, both in peacetime for intelligence gathering and in times of armed conflict. For example, in its threat assessment for 2022, DNB notes that state actors have attempted to gain access to the bank’s computer systems, although these attempts occur far less frequently than attempts made by criminal actors.23 At the same time, it is difficult to draw a clear distinction between criminal and state threat actors, because, among other things, organised crime sells their services to state actors and state actors are also profit-seeking.

With increasing professionalisation and specialisation among threat actors, cybercrime is becoming increasingly complex and difficult to defend against. The Norwegian National Security Authority (NSM) points out that vulnerable supply chains are increasingly being targeted. Cyber criminals search for security gaps in widely used software, which in many instances they are able to exploit before the gap is identified. This gives financial system participants very little time to defend at-risk systems. Supply chain attacks are still expected to pose an important threat. The same applies to ransomware attacks, which DNB sees as its primary threat.

Cyber attacks are being extensively used in the war in Ukraine. So far, the war has not led to an increased number of attacks against the Norwegian financial system, but the threat landscape has become more unpredictable and difficult to gauge. Hacktivist and cyber crime groups have actively taken sides in the conflict and executed cyber attacks against targets that they perceive to be serving Ukrainian or Russian interests. At the end of June, a pro-Russian group carried out a denial-of-service attack against a number of Norwegian websites that provide important services to the population.24 The attacks had limited consequences but showed that Norway is considered a target. Norwegian entities can also be impacted indirectly by spillovers from cyber attacks aimed at the warring parties. The risk of attack against the Norwegian financial system may increase if the conflict escalates.

Cyber resilience must be strengthened further

Cyber resilience means being able to prevent attacks, but being able to detect and deal with attacks and to restore operations if an attack is successful is equally important. The individual entity’s efforts constitute the most important part of defence against cyber attacks. In Risk and Vulnerability Analysis 2022, Finanstilsynet points out that firms are working continuously to strengthen defences. Attacks are usually averted before they have an impact. In Finanstilsynet’s assessment, the key institutions in the financial infrastructure generally also have sound contingency plans. In Financial Infrastructure Report 2022, Norges Bank considers the Norwegian financial infrastructure to be secure and efficient but at the same time it also points out an increase in cyber threats.

Since the consequences of a cyber attack can propagate through the financial system, it is essential that different authorities and entities cooperate to keep the system secure. The Norwegian financial sector has a long tradition of cooperation between key participants. In the field of cyber resilience, cooperation is coordinated by the Nordic Financial CERT (NFCERT).25 Norges Bank is working with Finanstilsynet to introduce cyber resilience testing based on the Threat Intelligence-based Ethical Red Teaming framework in Norway (TIBER-NO) and is promoting knowledge-sharing between private entities through the TIBER-NO Forum.26

22 See Finanstilsynet (2022) “Risk and Vulnerability Analysis 2022”.

23 See DNB (2022) “DNBs trusselvurdering for 2022” [Threat assessment 2022] (in Norwegian only).

24 See Norwegian National Security Authority’s webpage (in Norwegian only).

25 Nordic Financial CERT is a non-profit organisation. Its purpose includes sharing threat intelligence and information about vulnerabilities and assisting financial institutions in dealing with cyber attacks, see NFCERT’s website.

26 See Financial Infrastructure Report 2022, page 14.

1.4 Wider use of crypto-assets can be a source of systemic risk

Concepts in crypto-assets

Crypto-assets encompass a number of asset types based on distributed ledger technology (DLT). A number of cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin and Ether, function as infrastructures for different tokens and applications in decentralised finance.

Stablecoins are tokens, which through different mechanisms aim for a stable value against a reference, normally USD. See box on page 17 in Financial Infrastructure Report 2022 for a glossary of terms.

The increased exposure of institutional investors and financial institutions to crypto-assets can become a source of systemic risk. Abrupt and steep falls in crypto-asset values can inflict large losses, and if the crypto-asset is widely adopted, fire sales of other assets to cover leveraged positions can lead to financial instability.

There is currently limited information on Norwegian banks’ direct or indirect crypto-asset exposure. The capital framework for banks indicates that this exposure is small. In a consultation from the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, rules are being proposed to clarify that as a main rule, banks’ exposure to unsecured crypto-assets must be fully financed by equity. Rules are also being proposed to improve banks’ reporting of crypto-asset exposures.27 The value of crypto-assets has been highly volatile and has fallen markedly so far in 2022 (Chart 1.15).

Chart 1.15 The market value of crypto-assets has fallen markedly the past year28 Market value of crypto-assets. In trillions of USD

According to the tax authorities, more than 40 000 individuals owned crypto-assets in 2021 with an assessed value for 2021 totalling NOK 20m.29 In a March 2022 survey conducted by Arcane Research and EY, over 400 000 Norwegians are estimated to have owned cryptocurrencies in 2022, an increase from the 2021 estimate of 300 000.30 Both Norwegian and global institutional investors have crypto-asset exposures. One example is the Norwegian company Seetee, in which the Aker Group has a large stake. A number of international financial institutions have also entered the market.31 Closer linkages between crypto-assets and traditional finance can be a source of systemic risk, particularly in countries with substantial crypto-asset exposure.32 Surveys have shown a positive correlation between prices for crypto-assets and equities,33 which may indicate systemic risk owing to contagion between markets for crypto-assets and equities.

Stablecoins and their stabilisation mechanisms are another source of systemic risk. Stablecoins are stabilised in different ways. Market leaders, such as USD Circle, are stabilised using traditional assets. Selected market participants can exchange such stablecoins for a national currency at a fixed exchange rate. Other stablecoins are backed by crypto-assets and automatic liquidity mechanisms. Loss of confidence in asset-backed stablecoins can lead to fire sales of the underlying assets and potential losses for all owners of these or similar assets. Algorithm-based stablecoins34 are based on confidence in the stabilisation mechanisms. The collapse of USD Terra (UST) in the beginning of May 2022 is an example of how a loss of confidence can result in abrupt and steep price declines. Prior to the collapse, UST was the third largest stablecoin by market value.

If stablecoins or other crypto-assets come to play a substantial role in the payment system, loss of confidence can lead to a situation where payments cannot be executed. CPMI-IOSCO, an international body for payment and securities market authorities, has prepared guidelines for requirements for stablecoins used in systemically important payments, such as securities settlement. The guidelines are in accordance with general financial infrastructure requirements.35

Crypto-assets are relevant in a number of policy areas. Key regulatory themes are strengthening financial stability, preventing criminal applications, consumer protection and market integrity. Many authorities and international government bodies36 have pointed out the increased importance of crypto-assets to systemic risk even though crypto-assets are not currently deemed to constitute a significant risk to financial stability in Norway or globally. A statement issued by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) in July underlined the need for an internationally coordinated framework grounded in the principle of “same activity, same risk, same regulation”.37 In a report from October, the FSB elaborated on regulatory approaches.38 The European Commission’s proposed Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCA) has been debated by the Council and the Parliament.39

New rules will reduce the destabilising effects of crypto-assets, although many challenges remain. Access to data and relevant indicators are one challenge; regulatory gateways for holding decentralised system participants liable are another. Norges Bank will contribute to decision bases and help to draft rules for promoting responsible innovation.

27 See The Basel Committee of Banking Surpervision (2022) “Prudential treatment of cryptoasset exposures – second consultation”. Consultative Document. BIS, June 2022.

28 Period: 1 October 2021 – 3 November 2022

29 See the Norwegian Tax Administration’s website (in Norwegian only).

30 See Arcane Research and EY (2022) “Norwegian Crypto Adoption Survey 2022”.

31 See Auer, R., M. Farag, U. Lewrick, L. Orazem and M. Zoss (2022) “Banking in the shadow of Bitcoin? The institutional adoption of cryptocurrencies”. BIS Working Papers no 1013. BIS. See also OECD (2022) “Institutionalisation of crypto-assets and DeFi–TradFi interconnectedness”. OECD Business and Finance Policy papers. OECD, May 2022.

32 See European Securities and Markets Authority (2022) “Crypto-assets and their risks for financial stability”. ESMA Newsletter. ESMA, October 2022 and Drakopoulos, D., F. Natalucci og E. Papageorgiou (2021) “Crypto Boom Poses New Challenges to Financial Stability”. Blog post published on IMF Blog 1. September 2021. IMF.

33 See Adrian, T., T. Iyer og M.S. Qureshi (2022) “Crypto prices move more in sync with stocks, posing new risks”. Innlegg publisert på IMF Blog 11. januar 2022. IMF.

34 See Financial Infrastructure Report 2022 for a more detailed description of algorithmic stablecoins.

35 See CPMI-IOSCO (2022), ”Application of the Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures to stablecoin arrangements”. Consultative Report. BIS, July 2022.

36 See International Monetary Fund (2022) «Global financial stability report – April 2022», Bank for International Settlements (2022) «Annual Economic Report 2022», European Central Bank (2022) “Mining the environment – is climate risk priced into crypto-assets?” Macroeconomic Bulletin 18. ECB, July 2022 and The White House (2022) “Executive Order on Ensuring Responsible Development of Digital Assets” – March 2022.

37 See FSB (2022) “FSB issues statement on the international regulation and supervision of crypto-asset activities”. FSB, 11 July 2022.

38 FSB (2022), “Regulation, Supervision and Oversight of Crypto-Asset Activities and Markets”. Consultative Document. FSB, 11 October 2022.

39 For progress, see European Parliament (2022), “Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the council on markets in crypto-assets”. European Parliament, February 2022.

1.5 The financial system is resilient, thanks to its robustness and the measures implemented

Since the financial crisis in 2008, Norwegian authorities have introduced a number of regulations (see “Important measures in the financial system in Norway”). The measures that have been introduced help improve financial system resilience and can mitigate vulnerabilities.

Several of the measures addressing structural vulnerabilities affect banks’ total capital requirements, such as requirements for the systemic risk buffer (SyRB), risk-weighting requirements, and a minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL). There are also requirements for banks’ liquidity and credit standards. Cyber resilience of financial institutions will be tested according to the TIBER framework.

The Lending Regulation’s requirements for loan-to-value ratios, debt servicing capacity and debt-to-income ratios have a dampening effect on borrowing by many households, which reduces their vulnerability to a fall in house prices, income loss and higher interest expenses. Norges Bank is of the opinion that the Regulation’s debt-to-income ratio requirements and the flexibility quotas can continue to apply unrevised at present.40 The current Regulation strikes a good balance between curbing the build-up of household vulnerabilities and providing access to credit. In June, the Bank pointed that a broad review of the Regulation should be conducted before it expires in 2024, and that changes to the interest rate stress test should be considered based on the experience of higher interest rates ahead.

In autumn 2021, Norges Bank was given formal advisory responsibility for the SyRB, and in June, the Bank published a framework for providing advice on the SyRB rate (see “Norges Bank’s advice on the systemic risk buffer”). Norges Bank’s Monetary Policy and Financial Stability Committee has decided to advise the Ministry of Finance to retain the 4.5% SyRB rate for all exposures in Norway, applicable to all banks.41 In Norges Bank’s assessment, key structural vulnerabilities in the Norwegian financial system are broadly at the same level as when the decision was made to raise the SyRB rate to 4.5%. It is further assessed that an SyRB rate of 4.5% contributes to banks holding sufficient capital to withstand future downturns (see Section 3).

The countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) should reflect the assessment of cyclical vulnerabilities in the financial system. The CCyB is intended to strengthen banks’ solvency and mitigate the risk that banks amplify an economic downturn. In March 2022, Norges Bank decided to increase the CCyB rate to 2.5%, effective from 31 March 2023. According to the capital framework, the CCyB rate should, in principle, be set between 0% and 2.5%. Norges Bank is of the view that the CCyB rate should normally be in the higher part of this range. Analyses of the need for time-varying capital buffers, such as stress tests, lend support to this view. If a downturn will or could cause a markedly reduction in credit supply, the CCyB rate should be lowered.

The floor for average risk weights is also intended to ensure sufficient bank capital levels. If IRB risk weights are below the floor, banks must hold more capital. The Ministry of Finance has requested Finanstilsynet’s assessment of the need to retain or change the floors from end-2022. Finanstilsynet has exchanged assessments and information with Norges Bank. Norges Bank recommends retaining the floors for IRB banks’ risk weights for residential mortgages and CRE loans at the current levels.42 Financial system vulnerabilities are at broadly the same level as at the time the risk-weight floors were introduced. The Bank’s calculations, based on data going back to the banking crisis in the early 1990s, indicate that the current risk-weight floors are at a level that will prevent bank capital from becoming too low. Furthermore, banks incentives for maintaining sound risk management should be retained, which suggests that the risk-weight floors should not be the binding requirement.

The capital requirements contribute to the solvency of Norwegian banks. Analyses show that Norwegian banks’ current capital levels are in line with updated studies of how much equity capital banks should hold in the long term (see Section 3). In the analysis, weight is given to the economic costs and benefits of capital requirements. Norwegian banks are also profitable, and their funding structure is resilient. This strengthens banks’ loss-absorbing capacity, lending capacity and ability to withstand market turbulence, which increases financial system resilience. Stress tests show that in a pronounced downturn, where large shocks to the Norwegian economy are amplified by financial system vulnerabilities, the current capital buffers of the largest Norwegian banks are sufficient to absorb losses (see Section 3). Downturns can occur abruptly and come from unexpected sources. The current situation in the Norwegian and global economy illustrates the importance of maintaining financial system resilience. In Norges Bank’s overall assessment, the Norwegian financial system is well equipped to meet the risks we are facing in the current situation. Norges Bank’s advice that the SyRB rate should be maintained contributes to maintaining a resilient banking sector.

40 See Norges Bank’s letter to the Ministry of Finance on 9 November 2022 (in Norwegian only).

41 See Norges Bank’s letter to The Ministry of Finance on 9 November 2022.

42 See Norges Bank’s letter to Finanstilsynet on 26 October 2022 (in Norwegian only).

Norges Bank’s advice on the systemic risk buffer

The systemic risk buffer (SyRB) is a part of banks’ total capital requirement and one of the macroprudential instruments used in Norway. The SyRB is intended to increase banking system resilience by ensuring that the banks hold a capital buffer based on the level of structural vulnerabilities in the financial system. The Ministry of Finance sets the SyRB rate. Norges Bank is responsible for preparing a decision basis and providing advice on the SyRB rate to the Ministry of Finance at least every other year. The decision basis is to contain analyses based on relevant indicators, recommendations and guidance from the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) as well as Norges Bank’s assessment of structural vulnerabilities and other systemic risks of a long-term nature. When formulating the decision basis, information and assessments are exchanged with Finanstilsynet.

Purpose of the SyRB

Experience shows that the financial system can trigger and amplify economic downturns. Financial system vulnerabilities can amplify shocks, leading to more serious consequences for the economy. The SyRB is intended to strengthen banks’ solvency during a downturn.

No specific criteria have been laid down in the EU capital framework for deciding on the SyRB rate, but the rate must be justified on the basis that risks are not sufficiently addressed by the other capital requirements. There is no upper limit for the SyRB rate, although for SyRB rates between 3% and 5%, the EFTA Standing Commitee must provide its opinion, and the macroprudential authority in that member state must comply with that opinion or give reasons for not doing so (“comply or explain”). SyRB rates above 5% require the authorisation of the EFTA Standing Commitee. A country with an SyRB rate can request that the ESRB recommend reciprocation of this SyRB rate.

Norges Bank’s assessment of the SyRB rate

Norges Bank has developed three main principles for their advice on the SyRB (see Norges Bank Papers 5/2022 “A framework for advice on the systemic risk buffer requirement”):

- The SyRB rate should reflect the assessment of structural vulnerabilities in the financial system.

- The SyRB is intended to contribute to ensuring that banks hold sufficient capital to weather future downturns.

- The SyRB should as a main rule apply to all exposures in Norway.

Advice on the level of the SyRB is based on assessments of four different elements: Structural vulnerabilities in the financial system, other macroprudential measures, banks’ overall capital needs and banks’ responses to a change in the SyRB rate. The assessment of structural vulnerabilities is based on a set of indicators that reflect these elements (see Norges Bank’s website).

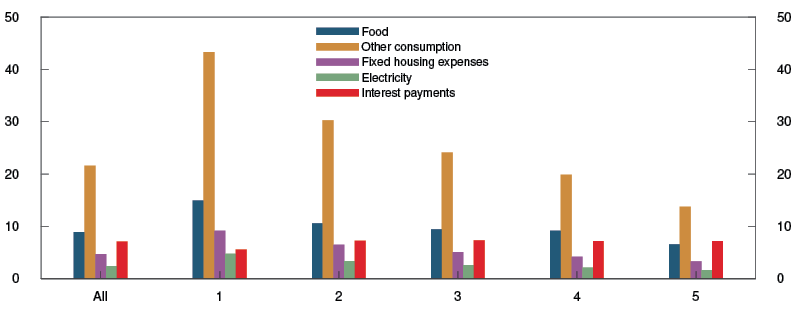

Households are resilient to moderate increases in interest rates and other expenses

In 2022, Norwegian households have faced increased expenses for electricity and food and rising interest expenses. Households that cannot cover current expenses are at risk of defaulting on their debt. The analysis shows that households without enough income and available wealth to cover normal expenses and interest payments during the 2020 reference year accounted for close to 1% of total debt. In a sensitivity test with expected 2023 residential mortgage lending rates, the share increases to just over 2%. However, in a stress test with higher food and electricity prices and where interest rates approach 10%, the share rises to over 15%. In such a stress situation, higher losses on bank lending to households can be expected.

Over the past year, prices for essentials such as food and electricity have increased. Interest rates have risen and are expected to rise further. Close to 70% of Norwegian households are homeowners, and nearly all household debt is in the form of residential mortgages. The vast majority of these mortgages are floating-rate mortgages. The analysis sheds light on how higher expenses affect the number of homeowners that may experience difficulty servicing their debt.1 The exercise is static, ie it does not take into account that households can make a number of adjustments in response to higher expenses, such as reducing electricity consumption.

The calculations use actual figures for the individual household’s after-tax income, gross financial wealth, debt and housing, and estimated figures for normal living expenses and interest expenses. Normal living expenses are based on the National Institute for Consumer Research (SIFO) Reference Budget for Consumer Expenditure and reflects a level of consumption that households need in order to maintain a modest standard of living. Normal living expenses include costs related to owner-occupied housing, including electricity expenses. Many households have liquid funds to draw on in periods when expenses exceed income. This is particularly the case for older persons. It is therefore also assumed that a share of gross financial wealth can be used to cover expenses.2 It is further assumed that homeowners with low debt-to-value ratios can cover expenses by borrowing.3 This analysis focuses on the ability to cover the most essential current expenses. Principal repayments and provisions for necessary residential maintenance are excluded.