Executive Board’s assessment

The Executive Board

26 April 2023

1. Security and contingency arrangements

Risks have intensified and the threat landscape has expanded in recent years. Maintaining a secure payment system requires the efforts of individual entities and effective public-private cooperation. Cyber incidents can quickly spread across sectors, and contingency work in the various sectors must therefore be viewed in a broader context.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the current geopolitical situation have intensified risks and expanded the threat landscape. Norway is one of the world’s most digitalised countries. Cyber attacks are a weapon of war and conflict. Cyber incidents can spread quickly across sectors and potentially impact financial stability. Resilience against cyber attacks needs to be strengthened, and public-private coordination is needed. In May 2023, the Norwegian National Security Authority (NSM) published a number of recommendations in the area of security intended to increase cyber resilience in Norway.1

Faults and disruptions in the financial infrastructure and other critical infrastructure, such as electricity, telecommunications and the internet, can impair the ability to make payments and maintain other critical functions. The societal impact of a payment system disruption may be more pronounced than the consequences for the system’s owners. The payment system is therefore subject to strict security, regulatory and supervisory requirements.

Security and contingency work requires the efforts of individual entities at sectoral and cross-sectoral level: Secure financial market infrastructures (FMIs) with effective solutions in place to deal with disruptions and faults are the first line of defence in the payment system’s contingency arrangements. Collaboration between public authorities and private payment system operators strengthens contingency arrangements at a sectoral level. An array of alternative means of payment also contributes to the payment system’s overall contingency arrangements. Adverse events can have a wide-ranging impact and spread across sectors via interconnectedness and interdependencies. Together with intensified risks and the expanded threat landscape, this has highlighted an increased need for comprehensive sectoral and cross-sectoral contingency arrangements.

Norges Bank’s supervision and oversight of individual FMIs

Banks settle payments made in NOK with finality in Norges Bank’s settlement system (NBO). In recent years, considerable resources have been devoted to strengthening the security of NBO by improving security controls and security surveillance and by increasing internal capacity.

Norges Bank is a supervisory and oversight authority for individual FMIs (see further discussion of Norges Bank’s responsibilities in the Annex). System operation and development of FMIs has largely been outsourced. IT providers are therefore crucial for critical functions in the payment system and other FMIs. Even though these tasks have been outsourced, responsibility for them rests with FMI owners. For Norges Bank, it is important that FMIs are required to maintain sufficient expertise and capacity for managing and controlling deliveries from IT providers. In Norges Bank’s assessment, there is still a need to reduce dependence on providers to ensure that, when necessary, switching providers is efficient and robust. For this to also be a realistic alternative in any situation, including when a change needs to occur at short notice, FMI owners must have made preparations for efficient switching of providers in plans and contracts and in terms of resources and expertise. Norges Bank follows up on this in its supervisory and oversight work.

Intensified risks and an expanded threat landscape raise questions regarding the resilience of critical infrastructure to extraordinary situations that not long ago were considered to be unrealistic worst-case scenarios. Contingency arrangements need to be strengthened. Critical infrastructure must be subject to national governance and control in order to ensure adequate continuity and back-up solutions, so that necessary and effective measures can be implemented in a contingency situation. Requirements for critical infrastructure to be operated in Norway or for operational back-up solutions to be established in Norway can facilitate supervisory and oversight efforts at national level and ensure that critical systems are available in crisis situations. On the other hand, operational or back-up solutions located outside of Norway may increase system availability in other crisis scenarios.

The use of cloud services is becoming increasingly common (see box). A number of financial and non-financial businesses are shifting from a strategy where cloud services are used primarily for support functions to one where the use of cloud services is expanded to include core functions. Large cloud service providers contribute to innovation and the development of services, including IT security, by utilising economies of scale. At the same time, the use of cloud platforms presents many of the same challenges as a more conventional operating environment. Many IT security incidents normally stem from system misconfiguration and complexity. System owners therefore need sufficient expertise and resources and a strong security culture in order to manage and control IT deliveries satisfactorily. Solutions must also be designed to be secure and easy to use and administer.

Cloud services

Cloud services are a collective term for everything ranging from data processing and storage to software available from third-party server parks.

Cloud services are normally divided into different operational models that provide customers with a certain degree of control of applications, networks, servers, operating systems and storage options. Typically, computing power can be adapted to customers’ capacity needs, and customers only pay for what they actually use. Installation, operation and updating processes can be simpler and more efficient compared with a traditional operating environment.

The cloud services market is dominated by three global tech giants (Google, Amazon and Microsoft). Incidents at cloud service providers can have a global impact. The internal security incident in Microsoft’s Azure cloud platform in September 2022 illustrates how broad the repercussions of an incident can be. A misconfiguration exposed the data of around 65 000 customers. The incident is referred to as “Bluebleed”.

NSM’s February 2023 report Risiko 2023 [Risk 2023] highlights the vulnerability ensuing from Norway’s national dependence on a very small number of foreign cloud service providers and a handful of large, centralised data centres.2

To reduce Norway’s overall dependence on international cloud platforms, NSM has worked on developing concepts for providing secure, efficient and flexible services for the central government administration. A number of alternatives with varying degrees of state ownership and control will be considered in NSM’s study, with concept proposals scheduled to be ready by June 2023.

Norges Bank’s work at a sectoral level

Norges Bank is tasked with overseeing the payment system and other financial infrastructure and contributing to contingency arrangements.

In Norges Bank’s view, an assessment should be made of whether, in addition to individual FMI’s continuity and contingency arrangements, other contingency arrangements independent of the ordinary payment system are needed. In that case, such solutions would come in addition to the individual FMI’s continuity and contingency arrangements.3 Norges Bank would like to engage in a dialogue with other authorities and the industry in this regard.

Cash is part of overall contingency arrangements should the payment system fail. Norges Bank is responsible for supplying banks with cash and meeting the public’s demand for cash, even in crisis situations. Norges Bank is assessing how cash-related contingency arrangements in the Bank’s area of responsibility should be adapted to an evolving risk and threat landscape. This concerns measures to ensure that Norges Bank is capable of meeting the need for more cash in different crisis situations. Norges Bank also points out certain actions that households can take to strengthen their payment contingency arrangements (see discussion in "Consumer preparedness in the area of payments"). In the assessment of whether Norges Bank should issue a central bank digital currency (CBDC), contingency arrangements are key considerations (see also "2.2 Central bank digital currencies").

Effective information sharing and cooperation are essential for dealing with critical incidents quickly. An example of such cooperation between financial institutions is the sharing of information about digital threats, vulnerabilities and security incidents through Nordic Financial CERT4 (NFCERT). NFCERT was established in 2017 and has members in all Nordic countries. The Financial Infrastructure Crisis Preparedness Committee (BFI) is an example of a public-private collaboration. The BFI brings together authorities and private entities to prevent and coordinate the handling of incidents with the potential to cause major disruptions to the financial infrastructure. The BFI conducts annual exercises.

In recent years, Norges Bank has collaborated with Finanstilsynet on the introduction of cyber security testing in accordance with TIBER-NO5, the national adaptation of the TIBER-EU framework developed by the European Central Bank (ECB). The purpose of TIBER testing is to increase the resilience of the banking and payment system against cyber attacks that can have systemic consequences.

TIBER has been introduced in Norway in consultation with the industry. Finanstilsynet and Norges Bank have identified critical functions in the banking and payment system, and the entities responsible for these functions participate in the TIBER-NO Forum. This means that they will test cyber resilience in accordance with the Norwegian implementation of TIBER-EU, with the first tests in Norway carried out in autumn 2022. TIBER tests simulate real attacks and provide insight into individual entities’ vulnerabilities and vulnerabilities that may have systemic consequences and implications for financial stability. A standardised testing programme is intended to ensure quality and comparability of experience with testing, also across countries. A separate TIBER-Cyber Team (TCT-NO) has been established at Norges Bank to guide entities through the testing process.

TIBER will be one of a number of possible testing frameworks under the Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA), which is a recently adopted EU legislative package (see "New EU/EEA rules for digital operational resilience in the financial sector").

Cross-sectoral contingency arrangements

The Government white paper Meld. St. 9 (2022–2023) “Nasjonal kontroll og digital motstandskraft for å ivareta nasjonal sikkerhet” [National control and digital resilience to safeguard national security] (Norwegian only) discusses the need for a uniform and long-term society-wide approach to national security. The white paper refers to the need for enhanced national security measures in the light of the geopolitical situation. Recommended measures include regulation and national ownership and control, a detailed inventory of security assets and increasing expertise and knowledge.6

To follow up the white paper, on 5 May, the Government presented a new digital security bill. If enacted, it will oblige entities with a particularly important role to maintain critical societal and economic activity, to comply with digital security requirements and report serious digital incidents. This will better equip entities to resist attacks on the digital systems on which they depend.7

The payment system is dependent on other critical infrastructure such as electricity, telecommunications and the internet. Measures that increase the resilience of other critical infrastructure are therefore vital for the payment system. A uniform approach to monitoring the security of critical societal infrastructure means that the same principles for governance and control should apply across sectors. This applies, for example, to outsourced cloud services, data centre services and IT services that provide support to fundamental national functions.

The Act relating to National Security (Security Act) is a cross-sectoral regulatory framework that is intended to safeguard the most critical functions in Norway. Each Ministry is responsible for identifying basic national functions in their sectors. The Ministry of Finance has identified two such functions relevant in this context: “the ability to finance the public sector” and “safeguarding society’s financial intermediation capabilities”. Furthermore, the ministries are tasked with designating entities of significant or material importance to basic national functions and any sensitive assets on which they depend. Norges Bank and Finanstilsynet assist the Ministry of Finance in this work and also participate in the Norwegian National Security Authority’s forum for supervisory authorities in the area of cyber security.

In July 2022, the draft of a new Electronic Communications Act with a proposal to regulate data centres in Norway was circulated for comment in a supplemental consultation by the Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development. In its consultation response, Norges Bank also emphasised the concentration risk posed by the dependence of a number of critical functions on a few key IT service providers and data centres. Such concentration risk may be difficult to manage by individual FMI owners. Norges Bank welcomes the proposal to supervise data centres and strengthen their contingency arrangements.

Consumer preparedness in the area of payments

Norway is one of the world’s most digitalised countries, also in terms of payment methods. FMIs’ continuity and contingency arrangements are the first line of defence in dealing with disruptions and serious incidents affecting electronic payment services. The repercussions of technical disruptions of electronic payment systems for consumers may be limited if each consumer has an array of payment options available. This could mean having different types of payment cards, accounts in more than one bank and a little cash on hand. Norwegian banks are solid and liquid, and the deposit guarantee scheme covers deposits of up to NOK 2m. Nevertheless, holding accounts in more than one bank increases consumers’ ability to make payments in the event of technical disruptions at a single institution.

Cash can be used even when the electronic back-up arrangements for the payment system are not functioning, but in some situations, cash can be difficult to obtain. Holding some cash will strengthen the individual consumer’s preparedness in the area of payments in situations where electronic back-up solutions are not functioning. According to the Norwegian Directorate for Civil Protection (DSB), in order for the authorities to prioritise resources in a crisis, individual contingency arrangements need to be robust. The DSB assumes that households should be equipped to manage on their own for at least three days. Holding some cash is part of this contingency preparedness. The amount of cash that individuals should hold depends on the size of the household and their current stock of basic necessities.

New EU/EEA rules for digital operational resilience in the financial sector

Digital resilience and security requirements for the financial sector will be strengthened by the introduction of the EU Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA). DORA and related regulatory technical standards will apply to the financial sector in the EEA and enter into force in 2025. DORA will supplement existing rules, superseding those in case of overlap.

The financial sector is becoming increasingly dependent on IT, with its complex value chains and dependencies on service providers. DORA is intended to promote innovation and competition and strengthen work on digital resilience in the financial sector and across sectors. An important aim is strengthening defences against cyber attacks.

DORA sets requirements for risk management, operational resilience testing, incident classification and reporting, monitoring third-party IT providers and information sharing. The requirements are proportional in the sense that requirements are stricter for entities that are larger or represent a potential systemic risk. Frameworks and forums are to be established at European level for monitoring providers to the financial sector.

The development of related regulatory technical standards was initiated in 2023 Q1 with different timelines and is being carried out by working groups established by European financial supervisory authorities. Finanstilsynet participates in the formulation of related regulatory technical standards as Norway’s representative, while maintaining a close dialogue with Norges Bank. The design of related technical standards will have implications for the focus and implementation of TIBER testing.

Financial supervisory authorities will be responsible for following up DORA, with Finanstilsynet assuming this role in Norway. For functions identified by Finanstilsynet as critical or important, advanced threat intelligence-based security testing will be required at least every three years, corresponding to testing methodologies under the TIBER framework.

1 See NSM (2023a) (in Norwegian only).

2 See NSM (2023b) (in Norwegian only).

3 This effort must be delineated from the work planned for a commission to study the future role of cash. In Financial Market Report 2022, the Government announced its intention to establish such a commission. See Norwegian Government (2022a).

4 Computer Emergency Response Team.

5 Threat Intelligence-Based Ethical Red-teaming.

6 See Norwegian Government (2022b) (in Norwegian only).

7 See Norwegian Government (2023) (in Norwegian only).

1. Security and contingency arrangements

Risks have intensified and the threat landscape has expanded in recent years. Maintaining a secure payment system requires the efforts of individual entities and effective public-private cooperation. Cyber incidents can quickly spread across sectors, and contingency work in the various sectors must therefore be viewed in a broader context.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the current geopolitical situation have intensified risks and expanded the threat landscape. Norway is one of the world’s most digitalised countries. Cyber attacks are a weapon of war and conflict. Cyber incidents can spread quickly across sectors and potentially impact financial stability. Resilience against cyber attacks needs to be strengthened, and public-private coordination is needed. In May 2023, the Norwegian National Security Authority (NSM) published a number of recommendations in the area of security intended to increase cyber resilience in Norway.1

Faults and disruptions in the financial infrastructure and other critical infrastructure, such as electricity, telecommunications and the internet, can impair the ability to make payments and maintain other critical functions. The societal impact of a payment system disruption may be more pronounced than the consequences for the system’s owners. The payment system is therefore subject to strict security, regulatory and supervisory requirements.

Security and contingency work requires the efforts of individual entities at sectoral and cross-sectoral level: Secure financial market infrastructures (FMIs) with effective solutions in place to deal with disruptions and faults are the first line of defence in the payment system’s contingency arrangements. Collaboration between public authorities and private payment system operators strengthens contingency arrangements at a sectoral level. An array of alternative means of payment also contributes to the payment system’s overall contingency arrangements. Adverse events can have a wide-ranging impact and spread across sectors via interconnectedness and interdependencies. Together with intensified risks and the expanded threat landscape, this has highlighted an increased need for comprehensive sectoral and cross-sectoral contingency arrangements.

Norges Bank’s supervision and oversight of individual FMIs

Banks settle payments made in NOK with finality in Norges Bank’s settlement system (NBO). In recent years, considerable resources have been devoted to strengthening the security of NBO by improving security controls and security surveillance and by increasing internal capacity.

Norges Bank is a supervisory and oversight authority for individual FMIs (see further discussion of Norges Bank’s responsibilities in the Annex). System operation and development of FMIs has largely been outsourced. IT providers are therefore crucial for critical functions in the payment system and other FMIs. Even though these tasks have been outsourced, responsibility for them rests with FMI owners. For Norges Bank, it is important that FMIs are required to maintain sufficient expertise and capacity for managing and controlling deliveries from IT providers. In Norges Bank’s assessment, there is still a need to reduce dependence on providers to ensure that, when necessary, switching providers is efficient and robust. For this to also be a realistic alternative in any situation, including when a change needs to occur at short notice, FMI owners must have made preparations for efficient switching of providers in plans and contracts and in terms of resources and expertise. Norges Bank follows up on this in its supervisory and oversight work.

Intensified risks and an expanded threat landscape raise questions regarding the resilience of critical infrastructure to extraordinary situations that not long ago were considered to be unrealistic worst-case scenarios. Contingency arrangements need to be strengthened. Critical infrastructure must be subject to national governance and control in order to ensure adequate continuity and back-up solutions, so that necessary and effective measures can be implemented in a contingency situation. Requirements for critical infrastructure to be operated in Norway or for operational back-up solutions to be established in Norway can facilitate supervisory and oversight efforts at national level and ensure that critical systems are available in crisis situations. On the other hand, operational or back-up solutions located outside of Norway may increase system availability in other crisis scenarios.

The use of cloud services is becoming increasingly common (see box). A number of financial and non-financial businesses are shifting from a strategy where cloud services are used primarily for support functions to one where the use of cloud services is expanded to include core functions. Large cloud service providers contribute to innovation and the development of services, including IT security, by utilising economies of scale. At the same time, the use of cloud platforms presents many of the same challenges as a more conventional operating environment. Many IT security incidents normally stem from system misconfiguration and complexity. System owners therefore need sufficient expertise and resources and a strong security culture in order to manage and control IT deliveries satisfactorily. Solutions must also be designed to be secure and easy to use and administer.

Cloud services

Cloud services are a collective term for everything ranging from data processing and storage to software available from third-party server parks.

Cloud services are normally divided into different operational models that provide customers with a certain degree of control of applications, networks, servers, operating systems and storage options. Typically, computing power can be adapted to customers’ capacity needs, and customers only pay for what they actually use. Installation, operation and updating processes can be simpler and more efficient compared with a traditional operating environment.

The cloud services market is dominated by three global tech giants (Google, Amazon and Microsoft). Incidents at cloud service providers can have a global impact. The internal security incident in Microsoft’s Azure cloud platform in September 2022 illustrates how broad the repercussions of an incident can be. A misconfiguration exposed the data of around 65 000 customers. The incident is referred to as “Bluebleed”.

NSM’s February 2023 report Risiko 2023 [Risk 2023] highlights the vulnerability ensuing from Norway’s national dependence on a very small number of foreign cloud service providers and a handful of large, centralised data centres.2

To reduce Norway’s overall dependence on international cloud platforms, NSM has worked on developing concepts for providing secure, efficient and flexible services for the central government administration. A number of alternatives with varying degrees of state ownership and control will be considered in NSM’s study, with concept proposals scheduled to be ready by June 2023.

Norges Bank’s work at a sectoral level

Norges Bank is tasked with overseeing the payment system and other financial infrastructure and contributing to contingency arrangements.

In Norges Bank’s view, an assessment should be made of whether, in addition to individual FMI’s continuity and contingency arrangements, other contingency arrangements independent of the ordinary payment system are needed. In that case, such solutions would come in addition to the individual FMI’s continuity and contingency arrangements.3 Norges Bank would like to engage in a dialogue with other authorities and the industry in this regard.

Cash is part of overall contingency arrangements should the payment system fail. Norges Bank is responsible for supplying banks with cash and meeting the public’s demand for cash, even in crisis situations. Norges Bank is assessing how cash-related contingency arrangements in the Bank’s area of responsibility should be adapted to an evolving risk and threat landscape. This concerns measures to ensure that Norges Bank is capable of meeting the need for more cash in different crisis situations. Norges Bank also points out certain actions that households can take to strengthen their payment contingency arrangements (see discussion in "Consumer preparedness in the area of payments"). In the assessment of whether Norges Bank should issue a central bank digital currency (CBDC), contingency arrangements are key considerations (see also "2.2 Central bank digital currencies").

Effective information sharing and cooperation are essential for dealing with critical incidents quickly. An example of such cooperation between financial institutions is the sharing of information about digital threats, vulnerabilities and security incidents through Nordic Financial CERT4 (NFCERT). NFCERT was established in 2017 and has members in all Nordic countries. The Financial Infrastructure Crisis Preparedness Committee (BFI) is an example of a public-private collaboration. The BFI brings together authorities and private entities to prevent and coordinate the handling of incidents with the potential to cause major disruptions to the financial infrastructure. The BFI conducts annual exercises.

In recent years, Norges Bank has collaborated with Finanstilsynet on the introduction of cyber security testing in accordance with TIBER-NO5, the national adaptation of the TIBER-EU framework developed by the European Central Bank (ECB). The purpose of TIBER testing is to increase the resilience of the banking and payment system against cyber attacks that can have systemic consequences.

TIBER has been introduced in Norway in consultation with the industry. Finanstilsynet and Norges Bank have identified critical functions in the banking and payment system, and the entities responsible for these functions participate in the TIBER-NO Forum. This means that they will test cyber resilience in accordance with the Norwegian implementation of TIBER-EU, with the first tests in Norway carried out in autumn 2022. TIBER tests simulate real attacks and provide insight into individual entities’ vulnerabilities and vulnerabilities that may have systemic consequences and implications for financial stability. A standardised testing programme is intended to ensure quality and comparability of experience with testing, also across countries. A separate TIBER-Cyber Team (TCT-NO) has been established at Norges Bank to guide entities through the testing process.

TIBER will be one of a number of possible testing frameworks under the Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA), which is a recently adopted EU legislative package (see "New EU/EEA rules for digital operational resilience in the financial sector").

Cross-sectoral contingency arrangements

The Government white paper Meld. St. 9 (2022–2023) “Nasjonal kontroll og digital motstandskraft for å ivareta nasjonal sikkerhet” [National control and digital resilience to safeguard national security] (Norwegian only) discusses the need for a uniform and long-term society-wide approach to national security. The white paper refers to the need for enhanced national security measures in the light of the geopolitical situation. Recommended measures include regulation and national ownership and control, a detailed inventory of security assets and increasing expertise and knowledge.6

To follow up the white paper, on 5 May, the Government presented a new digital security bill. If enacted, it will oblige entities with a particularly important role to maintain critical societal and economic activity, to comply with digital security requirements and report serious digital incidents. This will better equip entities to resist attacks on the digital systems on which they depend.7

The payment system is dependent on other critical infrastructure such as electricity, telecommunications and the internet. Measures that increase the resilience of other critical infrastructure are therefore vital for the payment system. A uniform approach to monitoring the security of critical societal infrastructure means that the same principles for governance and control should apply across sectors. This applies, for example, to outsourced cloud services, data centre services and IT services that provide support to fundamental national functions.

The Act relating to National Security (Security Act) is a cross-sectoral regulatory framework that is intended to safeguard the most critical functions in Norway. Each Ministry is responsible for identifying basic national functions in their sectors. The Ministry of Finance has identified two such functions relevant in this context: “the ability to finance the public sector” and “safeguarding society’s financial intermediation capabilities”. Furthermore, the ministries are tasked with designating entities of significant or material importance to basic national functions and any sensitive assets on which they depend. Norges Bank and Finanstilsynet assist the Ministry of Finance in this work and also participate in the Norwegian National Security Authority’s forum for supervisory authorities in the area of cyber security.

In July 2022, the draft of a new Electronic Communications Act with a proposal to regulate data centres in Norway was circulated for comment in a supplemental consultation by the Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development. In its consultation response, Norges Bank also emphasised the concentration risk posed by the dependence of a number of critical functions on a few key IT service providers and data centres. Such concentration risk may be difficult to manage by individual FMI owners. Norges Bank welcomes the proposal to supervise data centres and strengthen their contingency arrangements.

Consumer preparedness in the area of payments

Norway is one of the world’s most digitalised countries, also in terms of payment methods. FMIs’ continuity and contingency arrangements are the first line of defence in dealing with disruptions and serious incidents affecting electronic payment services. The repercussions of technical disruptions of electronic payment systems for consumers may be limited if each consumer has an array of payment options available. This could mean having different types of payment cards, accounts in more than one bank and a little cash on hand. Norwegian banks are solid and liquid, and the deposit guarantee scheme covers deposits of up to NOK 2m. Nevertheless, holding accounts in more than one bank increases consumers’ ability to make payments in the event of technical disruptions at a single institution.

Cash can be used even when the electronic back-up arrangements for the payment system are not functioning, but in some situations, cash can be difficult to obtain. Holding some cash will strengthen the individual consumer’s preparedness in the area of payments in situations where electronic back-up solutions are not functioning. According to the Norwegian Directorate for Civil Protection (DSB), in order for the authorities to prioritise resources in a crisis, individual contingency arrangements need to be robust. The DSB assumes that households should be equipped to manage on their own for at least three days. Holding some cash is part of this contingency preparedness. The amount of cash that individuals should hold depends on the size of the household and their current stock of basic necessities.

New EU/EEA rules for digital operational resilience in the financial sector

Digital resilience and security requirements for the financial sector will be strengthened by the introduction of the EU Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA). DORA and related regulatory technical standards will apply to the financial sector in the EEA and enter into force in 2025. DORA will supplement existing rules, superseding those in case of overlap.

The financial sector is becoming increasingly dependent on IT, with its complex value chains and dependencies on service providers. DORA is intended to promote innovation and competition and strengthen work on digital resilience in the financial sector and across sectors. An important aim is strengthening defences against cyber attacks.

DORA sets requirements for risk management, operational resilience testing, incident classification and reporting, monitoring third-party IT providers and information sharing. The requirements are proportional in the sense that requirements are stricter for entities that are larger or represent a potential systemic risk. Frameworks and forums are to be established at European level for monitoring providers to the financial sector.

The development of related regulatory technical standards was initiated in 2023 Q1 with different timelines and is being carried out by working groups established by European financial supervisory authorities. Finanstilsynet participates in the formulation of related regulatory technical standards as Norway’s representative, while maintaining a close dialogue with Norges Bank. The design of related technical standards will have implications for the focus and implementation of TIBER testing.

Financial supervisory authorities will be responsible for following up DORA, with Finanstilsynet assuming this role in Norway. For functions identified by Finanstilsynet as critical or important, advanced threat intelligence-based security testing will be required at least every three years, corresponding to testing methodologies under the TIBER framework.

1 See NSM (2023a) (in Norwegian only).

2 See NSM (2023b) (in Norwegian only).

3 This effort must be delineated from the work planned for a commission to study the future role of cash. In Financial Market Report 2022, the Government announced its intention to establish such a commission. See Norwegian Government (2022a).

4 Computer Emergency Response Team.

5 Threat Intelligence-Based Ethical Red-teaming.

6 See Norwegian Government (2022b) (in Norwegian only).

7 See Norwegian Government (2023) (in Norwegian only).

2. Central bank money and settlement

The payment landscape is marked by new technology, new payment methods and new payment providers. Norges Bank is tasked with providing a stable and efficient settlement system and ensuring that the Norwegian krone will be a secure, efficient and attractive means of payment in the future too.

2.1 Settlement system

Over the coming years, Norges Bank will study and decide on the future design of Norges Bank’s settlement system. A key question is whether the next generation settlement system will build on the current model or whether other solutions, such as participation in the Eurosystem’s settlement services for payments (T2), are more appropriate.

The current settlement system

Norges Bank’s settlement system (NBO) is designed to be a secure and efficient platform for settlement in NOK. Today’s NBO was introduced in 2009 and has delivered high-quality and stable services. Needed upgrades have been performed in recent years to ensure that the system is functional and technologically up-to-date, with a considerable effort devoted to increasing cyber resilience in the light of the evolving threat landscape.

Introduction of ISO 20022

Standard messaging formats developed by SWIFT (SWIFT FIN)8 are currently in use today for all payment messages and other communication to and from NBO. SWIFT messages contain a limited amount of information, and formats can vary across systems, which limits the ability of banks and their customers to automate payment processing.

There is a broad national and international consensus on a proposal to base payment messaging formats on the ISO 20022 standard, and in 2018, the SWIFT board of directors decided to fully migrate a number of existing SWIFT FIN messages for cross-border payments to ISO 20022. This standardisation will enable banks and other financial infrastructure participants to use messages across FMIs. In addition, increased cross-border standardisation will make it easier for banks to meet regulatory requirements (money laundering regulations, etc). The ISO 20022 format is more structured and will be able to contain more information than the previous messaging formats and thus facilitates increased automation and more efficient payment processing.

In 2020, Norges Bank initiated a project together with the banking industry to make the transition to ISO 20022 in NBO and other key parts of the payment infrastructure. Since autumn 2020, Norges Bank has collaborated with the central banks of Sweden and Iceland and the supplier of NBO’s core system to adapt the ISO 20022 messaging format for use in the Nordic region.

Norges Bank is planning to adopt the new ISO 20022 messaging format in NBO by November 2025.

Real-time payments

A well-functioning real-time payment solution is a key component of an efficient payment system. Real-time payments are payments where the funds are available in the payee’s account seconds after the payment is initiated. The share of payments settled in real time will likely increase in the coming years.

Norges Bank is exploring whether to offer real-time gross interbank settlement of retail payments in central bank money. The assessment so far is that participation in the Eurosystem’s TARGET Instant Payment Settlement (TIPS) service will be the best platform for developing Norwegian real-time payments in the years ahead. Following the Executive Board’s decision in October 2021, Norges Bank has entered into formal discussions with the ECB on possible participation in TIPS.9 A final decision on participation will be made once these discussions have been completed.

Work is in progress to expand Norway’s current real-time payment infrastructure to support government payments. Norges Bank has entered into dialogue with Nordea, DNB, the Norwegian Government Agency for Financial Management (DFØ) and Bits AS (Bits) to clarify how banks, DFØ and Bits can facilitate this type of payment.10 Among other things, this requires the banking industry to enable the use of payment identifiers (eg customer identification (CID) numbers) in the existing real-time payment infrastructure.11 One aim is for the solution to be independent of existing clearing and settlement systems, so that it can also be used in the event of Norway’s participation in TIPS.

Norges Bank’s settlement system

All electronic payments made in NOK are settled with finality between banks in NBO. This includes ordinary payments by households and firms, large payments in the financial and foreign exchange markets, and payments involving the public sector. NBO is also used to implement Norges Bank’s monetary policy.

NBO consists of a core Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) system for payment settlement and a subsystem to process banks’ collateral loans (SIL). The global SWIFT network is used as the primary channel for payment orders and other financial messaging.

Background for assessing the next generation settlement system

Norges Bank is now exploring the design of the next generation NOK settlement system.

There are several reasons for this exploration:

- Lifetime: The procurement process for the current core system (RTGS) started close to 20 years ago, and the system has been in operation for almost 14 years. Normally, a system’s expected lifetime is no longer than between 20 and 30 years, for both technical and functional reasons.

- Requirements: A system’s requirements will normally change during its lifetime. Most of the innovation is being driven by private agents, but it is Norges Bank’s responsibility that the payment system’s basic infrastructure permits innovation and international harmonisation, while safeguarding security and tailoring contingency arrangements to a more demanding risk landscape. Norges Bank will continue to develop the system’s basic infrastructure so that the Norwegian krone will be a secure and efficient means of payment in the future too.

- Dependency on service providers: The production of settlement services is dependent on both internal and external inputs along the entire value chain, ranging from electricity and telecommunications to data centres, hardware, operational providers, software providers and service providers. Over the past 20 years, these areas have seen sweeping changes, including acquisitions, consolidation and the internationalisation of the provider market. A key part of the assessment will be evaluating the concentration risk and dependency on service providers associated with the alternative models.

- Delivery models: Delivery models have largely changed from being dedicated systems to service deliveries. Non-euro area countries can participate in the Eurosystem’s payment and securities platform TARGET Services, which was not an option when the current settlement system was established.

- Partners: The RTGS has been managed in close cooperation with Sweden, Denmark and Iceland. Denmark has decided to join the Eurosystem’s TARGET Services platform from 2025, and Sweden's preferred direction going forward is to consider similar participation in the TARGET Services platform.12

- Harmonisation: Customers and banks operate across borders, which makes the international standardisation and harmonisation of financial services increasingly important for providing efficient and competitive financial services.

The time now appears to be right to carry out a comprehensive assessment as more than the half of the settlement system’s expected lifetime has passed, and needs, providers, delivery models and partners are changing. The geopolitical situation and future needs for contingency arrangements and cyber resilience make a such an assessment even more relevant.

Key issues

The key decision for the next generation settlement system once the study phase is complete will be whether the current model with a dedicated system should be continued or whether participation in the Eurosystem’s common platform is more appropriate. A hybrid model, where settlement services are provided in part from a dedicated platform and in part from a common platform, will also be considered.

In the assessments, key issues and considerations will be ascertained and analysed, such as:

- Secure and stable operation: Ability to provide settlement services in normal situations, disruptions and crises and ensure the necessary resilience to cyber attacks. This includes assessing the need to introduce new or alternative models for contingency arrangements adapted to future changes in the risk landscape.

- Functionality and availability: Ability to meet changes in the demand for settlement services and ensure adequate availability for market participants, where services are harmonised with a larger market. Clarifying what participation in the TARGET platform may mean for NBO participants in terms of new opportunities and added value is also relevant.

- Interoperability: Ability to communicate and seamlessly exchange data with other financial systems and platforms and compatibility with needed changes in market participants’ systems and infrastructure.

- Liquidity management and monetary policy: Ability to manage liquidity effectively, for both Norges Bank and market participants and to implement monetary policy.

- National governance and control: Assessment of the preventive security measures needed to provide a proper level of security for the various models in accordance with the provisions of the Security Act.

- Cost efficiency: Assessment of cost efficiency for Norges Bank and relevant market participants.

The process ahead

In the period to the end of 2025, Norges Bank will decide on the design of the next generation NOK settlement system. The study phase will continue until autumn 2024 and be followed by a final decision. Norges Bank will involve relevant government bodies, the financial industry and market participants, thus ensuring that important needs and considerations are taken into account.

Norges Bank is continuing its formal discussions with the ECB on participation in TIPS, and the decision-making process will be coordinated with the overall assessment of the next generation settlement system.

The final decision on the design of the next generation NOK settlement system will have to stand for around 30 years, ie a time horizon of until at least 2050. A long time horizon and predictability regarding changes in both the basic payment system infrastructure and other critical infrastructure are important for creating the appropriate framework conditions for the development of NOK payment services also in the years to come.

8 See Norges Bank (2022a) for a further discussion.

9 See Norges Bank (2021a).

10 DFØ has entered into an agreement with DNB and Nordea for payment and account management services for government agencies. See Directorate for Public Administration and Financial Management (2022).

11 See Norges Bank (2022a) for a further discussion.

12 See Sveriges Riksbank (2021).

2.2 Central bank digital currencies

Norges Bank is assessing whether the public should have access to a central bank digital currency (CBDC) in addition to cash. A CBDC can serve as a means of settlement trusted by all, also in new payment arenas, promote responsible innovation and improve payment contingency arrangements. In the period to 2025, the Bank will analyse the possibilities afforded by a CBDC and its impact and test and evaluate candidate solutions. The Bank will evaluate various forms of a CBDC against the use of other instruments, such as regulation of private means of payment and payment systems. The assessment of CBDCs raises complex issues, and the current payment system in Norway functions well. This implies that we should not proceed with undue haste. Nevertheless, against the backdrop of falling cash usage, emergence of new money and payment systems and work of CBDCs in other countries, introducing a CBDC is regarded as more relevant now than when the Bank’s research into this issue began in 2016.

International developments

A CBDC is a digital form of central bank money for general purpose users. So far, only a few central banks in developing countries and emerging economies have introduced a CBDC.13 For the time being, the use of CBDCs appears to be fairly limited, which can be attributed to a number of factors, such as their novelty and unfamiliarity among the public.

Many central banks are studying CBDCs and are typically focusing on the objectives and ramifications of introducing a CBDC, necessary characteristics and legal implications. A number of central banks have developed different prototypes (simple test versions) to increase their knowledge about different technological solutions and how these solutions might help meet central banks’ objectives.

The ECB and the Eurosystem of central banks are now exploring design and distribution options for a digital euro.14 In autumn 2023, the ECB’s Governing Council will decide on whether to enter a new phase, including the development and testing of technical solutions. Sveriges Riksbank, the Bank of England, the Federal Reserve and the Bank of Japan are examples of other central banks that are studying a CBDC.

International organisations such as the IMF and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) are also devoting considerable resources to analysing various issues related to CBDCs. The BIS Innovation Hub has been established to experiment with ways in which new technology can strengthen the financial system, with CBDCs as a focus area.

Norges Bank’s research

Norges Bank is researching whether introducing a CBDC is appropriate for ensuring that the Norwegian krone will be a secure, efficient and attractive means of payment in the future too. Falling cash usage, the potential of new technologies, and prospects for the establishment of new money and payment systems are important drivers behind this research. Introducing a CBDC may ensure access to a means of settlement trusted by all, also in new payment arenas, promote responsible innovation and improve payment contingency arrangements.

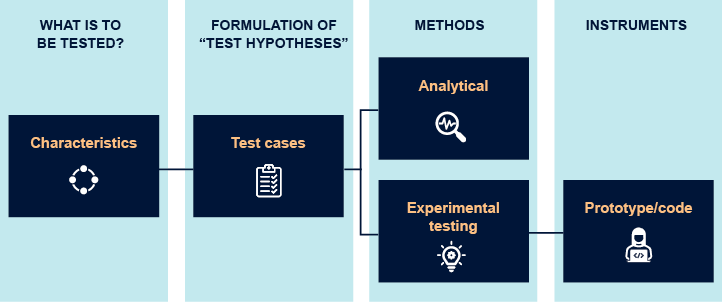

Norges Bank is now approaching the end of an exploratory phase of experimental testing of different technical solutions and has also continued to analyse the objectives and ramifications of introducing a CBDC.

The purpose of experimental testing is to gather further knowledge on how different technologies can deliver the necessary characteristics of a CBDC, while highlighting economic and regulatory issues related to the use of these technologies. Experimental testing will also help provide Norges Bank with the competence needed for assessing the future path of its work on a CBDC, including candidate technologies for further testing.

In this work, Norges Bank is in dialogue with a wide range of private stakeholders (including Norwegian and global tech and payment companies and banks established in Norway), public authorities, end-user representatives, other central banks and international organisations, such as the BIS. The Bank’s research includes considerable outreach activity. The Bank has organised a number of conferences, workshops and hackathons in collaboration with other stakeholders.

A CBDC, if adopted, needs to have a wide range of characteristics to fulfil its objectives.15 For example, a CBDC must have the same value as cash and bank deposits. To serve as a back-up solution, the CBDC system needs a sufficient degree of technical independence from systems operated by banks. The CBDC system must also fulfil statutory privacy requirements. In some cases, it will also be necessary to strike a balance between characteristics. For example, a CBDC must be controlled by Norges Bank, while at the same time promoting the development of third-party services.

Different test cases have shed light on how solutions can deliver the necessary characteristics of a CBDC (Chart 2.1). Examples from test cases are CBDC issuance and destruction, mass payments and cross-border payments. Analysis work and experimental testing have complemented each other. In areas where the Bank itself has not conducted adequate testing, the research has benefitted from tests and analytical work conducted by other parties.

Norges Bank is exploring several technological solutions for a CBDC. Both more traditional payment technology and token technology16 have the potential to retain some of the important characteristics of cash, while also enabling the use of central bank money for distance payments. At the same time, token-based solutions can offer innovative functionalities such as programmable payments. However, there is uncertainty associated with this technology, and further study is needed. For that reason, this technology has been the particular focus of experimental testing.

Norges Bank has primarily chosen to test technologies based on open-source code17. Open-source code provides the freedom to carry out testing without being dependent on access to proprietary technologies, which makes collaboration with vendors and alliance partners simpler and more flexible.

Testing has primarily involved using a prototype based on token technology and open-source code. The prototype is a simple core CBDC infrastructure: a register of money issued and functionalities for CBDC issuance, destruction, distribution and settlement. In September 2022, the prototype’s source code was made public as open source, thus enabling interested parties to experiment with the source code. More limited testing of other technologies has also been conducted.

Testing required Norges Bank to finance development projects and collaborate with alliance partners with a desire and capacity to participate in testing. A diverse array of market participants and stakeholders have participated.

Norges Bank has also participated in or closely followed studies and experimental testing of CBDCs around the world. The Bank has devoted the most time to “Project Icebreaker”, a research collaboration with Sveriges Riksbank, the Bank of Israel and the BIS Innovation Hub on a solution for cross-border payments using CBDCs.18 Through such collaboration, the Bank also learns more about different CBDC prototypes and how other central banks are studying CBDCs.

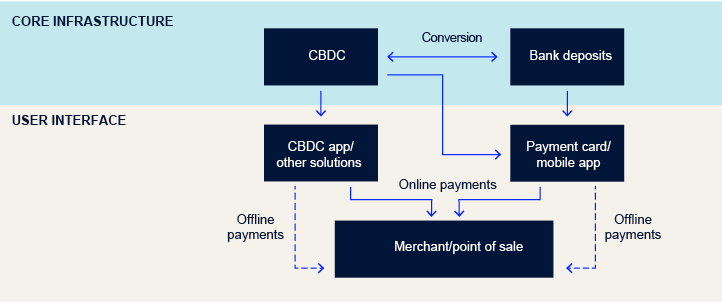

A CBDC as an independent contingency payment solution

To serve as a contingency payment solution, a CBDC system must be able to function with a sufficient degree of independence from payment systems operated by banks. This means that the same incident must not disable both the core CBDC infrastructure and the systems operated by banks at the same time. For contingency reasons, a CBDC must be able to be used with at least one payment instrument that is independent of payments using bank deposits. This does not prevent a CBDC from also being the source of money for some of the same payment instruments where bank deposits are also a source of money (Chart 2.2).

As a back-up, it is also an advantage that a CBDC can be used for payments where there is no contact between the register/account system and the user interface (offline payments). One solution is for the funds to be stored locally in the payment instrument and transfers between users made in close proximity.

Work going forward

The Bank is nearing the end of the current phase of its research into a CBDC, and the results will be published in the series Norges Bank Papers in autumn 2023.

This research has been ongoing since 2016, and resources have been limited compared with studies by other central banks. Introducing a CBDC raises complex issues, and the current payment system in Norway functions well, which implies that we should not proceed with a decision with undue haste. However, Norges Bank wishes to be well prepared if the introduction of a CBDC becomes necessary to ensure that the Norwegian krone will be an efficient, secure and attractive means of payment in the future too. Against the background of falling cash usage, emergence of new money and payment systems and work on CBDCs in other countries, introducing a CBDC is regarded as more relevant now than when the Bank’s research into this issue started in 2016.

Norges Bank’s CBDC work will be stepped up from autumn 2023. In line with the strategy for the period 2023–2025, the Bank will make preparations to introduce a CBDC. The Bank will continue to analyse the possibilities afforded by a CBDC and the ramifications of introducing one and will test and evaluate candidate solutions. To gather data and contribute to international standardisation and collaboration efforts, the Bank will work together with other central banks and international organisations. The Bank will also continue discussions and collaborate with stakeholders in Norway. As part of a decision basis, the Bank will assess various forms of CBDC against the use of other instruments, such as the regulation of private means of payment and payment systems. The final decision on whether to introduce a CBDC must be made by the Storting (Norwegian parliament).

13 The Bahamas, Nigeria, the Eastern Caribbean Economic and Currency Union and Jamaica have introduced a CBDC, while China, India, Ghana are Uruguay are running or have run pilot projects involving actual payments.

14 See ECB (2023).

15 See Norges Bank (2021b).

16 A token is an object of value in a cryptocurrency system. Cryptocurrencies are units in a distributed ledger or decentralised data system.

17 Open source code is source code that is made freely available for possible modification and distribution.

18 See BIS (2023).

19 An app (application) is a computer program that can be installed on a smartphone or other mobile device.

2.3 Cash

Even though cash usage is low, cash has characteristics that are essential to a secure and efficient payment system. In recent years, regulation has been introduced to increase cash availability. Furthermore, last year, the Ministry of Justice and Public Security circulated for comment a proposal to clarify consumers’ right to pay cash.

The share of cash payments at points of sale and between private individuals (person-to-person) has declined over many years and fell further during the pandemic. At the same time, society on the whole has become increasingly digitalised, and payment habits have changed. New types of money and payment systems and new operators have entered the market, thus reducing the importance of cash in normal situations for most people. Norway is one of the countries with the lowest cash usage in the world.20 In surveys conducted by Norges Bank, approximately 3%-5% of respondents report that they used cash for their most recent payment.21

Even though cash usage is low, cash will also play a key role in the payment system ahead. This is because cash has important characteristics and functionalities that other means of payment and payment instruments lack and that promote a secure and efficient payment system. Ultimately, cash is the only alternative if the electronic payment solutions should fail completely. Cash is also important for individuals who do not have the skills or opportunity to use digital payment solutions. In addition, cash is a claim on Norges Bank and thus without credit risk.22

For cash to be able to fulfil its functions, it must be sufficiently available and easy to use, ie ensuring that the general public has real opportunities to obtain and use cash.

Availability

In parallel with lower cash usage, banks have reduced their cash services over many years, which may undermine the ability to use cash in normal situations and as a contingency solution. Regulation is therefore necessary to ensure the sufficient availability of cash.

The main elements of such regulation are now in place. Section 16-4 of the Financial Institutions Act stipulates: “Banks shall, in accordance with customer expectations and needs, accept cash from customers and make deposits available to customers in the form of cash”. Section 16-7 of the Financial Institutions Regulation stipulates that this obligation also applies when demand for cash has increased as a result of disruptions in electronic payment systems.23 The obligation applies to all Norwegian banks and can be met under the auspices of the banks themselves or through an agreement with other cash service providers (cf Section 16-8 of the Financial Institutions Regulation).24

There are still shortcomings and vulnerabilities associated with the provision of cash services, particularly related to the ability of business customers to make cash deposits, and the banks’ provision of cash services are being increasingly funnelled through a single solution: “Kontanttjenester i butikk” (KiB) (in-store cash services). This solution requires the use of a BankAxept card and PIN code and depends on functioning point-of-sale (POS) terminals and electronic systems. KiB cash services will often be adequate for consumers but are not available to individuals that do not have a BankAxept card, nor do they meet the needs of business customers with larger volumes of cash.25

If the electronic payment system fails, a back-up solution is in place, which allows POS terminals to continue to function for some time. However, KiB cash services are unavailable when the back-up solution is in use. Thus, the back-up solution does not fulfil banks’ cash service obligations but may be taken into account in banks’ contingency planning. If the back-up solution is expanded to comprise cash withdrawals (and deposits) through in-store cash services (KiB), it could also be part of cash contingency arrangements.26

Norges Bank assumes that the clarification of banks’ cash service obligations will mitigate shortcomings and vulnerabilities associated with the provision of cash services ahead.

For many years, banks have worked together on a regulation related to cash withdrawals from ATMs using BankAxept cards. The owners of ATMs have been able to charge banks a specified amount (an interbank fee) when the banks’ customers use an ATM. Owners of ATMs have not been permitted to charge fees over and above this interbank fee. In recent years, the level of the interbank fee has been low relative to an ATM’s operating costs. The arrangement is the responsibility of Bits AS (Bits), and on 19 April 2023, the board of directors of Bits approved the phasing-out of the rules governing interbank fees for cash withdrawals from ATMs from 31 October 2023. ATM owners will then be able to establish their own business models for financing their ATMs and charge fees directly to ATM users. Norges Bank will closely monitor how this will affect developments in the area of cash services ahead.

Ease of use

Shops and service providers have been increasingly refusing cash as a means of payment for some time. Clarity regarding consumers’ right to pay cash is therefore crucial. On 1 September 2022, the Ministry of Justice and Public Security circulated for comment a proposal to strengthen consumers’ right to pay cash. The proposal is primarily a clarification of the current provisions of the Financial Contracts Act. In the consultation proposal, the right to pay cash is understood to be a right that cannot be rescinded by standard terms and conditions. Furthermore, businesses will be obliged to allow consumers to pay cash for goods and services sold in permanent, serviced business premises. The proposal is largely in line with previous input from Norges Bank. The Bank is of the opinion that the proposed clarification will be an important contribution in ensuring that cash remains easy to use and supported the proposal in the Bank’s consultation response.27 In its consultation response, the Bank refers to the importance of clearly defined sanctions to ensure consumers’ right to pay cash.28 Moreover, Norges Bank urged that this work be given priority.

Larger-scale failure of critical infrastructure

Banks are also responsible for ensuring that cash services are available to their customers in situations where electronic payment systems fail. To deal with more serious scenarios, such as a large-scale failure of critical infrastructure, banks cannot bear sole responsibility for arrangements to provide cash to customers. Before such a situation arises, there is a need to clarify what are considered appropriate cash contingency arrangements, along with the division of labour and responsibilities among governmental bodies, the banking industry and other entities.

20 The value of cash as a share of M1 is about 1.3%. Narrow money (M1) is defined as the money-holding sector’s holdings of Norwegian banknotes and coins and the sector’s deposits in transaction accounts in NOK and foreign currency.

21 See Norges Bank (2023).

22 Cash also plays a key role as legal tender and payment alternative that provides users with a choice and promotes competition. Cash also provides anonymity in payment situations, which is positive for individuals’ privacy needs but may be negative if used for economic crime.

23 Risk-mitigating effects of electronic contingency arrangements can be taken into account.

24 Section 16-8 of the Financial Institutions Regulation entered into force on 1 October 2022.

25 Norges Bank submitted its assessment of developments in the provision of cash services in a letter of 25 February 2021 to Finanstilsynet and the Ministry of Finance. See Norges Bank (2021c) for a further discussion.

26 See Norges Bank (2021c) and Norges Bank (2022b) for a further discussion of in-store cash solutions and POS terminal contingency arrangements.

27 See Norges Bank (2022b).

28 See Norges Bank (2019).

3. Crypto-asset regulation

The new EU Markets in Crypto-assets Regulation (MiCA) is expected to enter into force in the EU within one to two years and will probably also apply to Norway. Some types of risk associated with crypto-assets are covered by general regulations such as criminal law and regulations that also apply to other financial activity. At the same time there is a need for further development of specific regulations for crypto-assets. Other regulatory frameworks can also affect the scope of crypto-asset activity in Norway. Cross-border regulation is crucial. Norwegian authorities should nevertheless assess whether to proceed more quickly rather than wait for international regulatory solutions. Norges Bank will contribute to such assessments and to regulation that promotes responsible innovation.

Today, crypto-assets29 are primarily used for speculation and investment. There are no large institutional investors or financial institutions in Norway or internationally that have substantial exposures to crypto-assets, and they are still rarely used for ordinary payments. At the same time, other applications are evolving, such as decentralised finance.30 Cypto-assets may gain increased importance for financial stability and ordinary payments. Regulation is necessary both to protect users and to address societal considerations, such as combating crime and promoting financial stability.

International regulatory developments

A number of specially adapted crypto-asset regulations are under development. One of the aims of new rules proposed by the Basel Committee regarding capital requirements relating to banks’ crypto-asset exposures is to contribute to risk containment.31

In the EU, the Markets in Crypto-assets Regulation (MiCA) has been debated by the Council and the Parliament and is nearing final approval.32 MiCA will be applicable in all member states within 12–18 months of approval. MiCA applies to a range of service providers in crypto-asset markets and also covers different kinds of market abuse. The regulation is intended to promote consumer protection, market integrity, innovation and financial stability. The Ministry of Finance will assess EEA relevance and implementation in Norway.

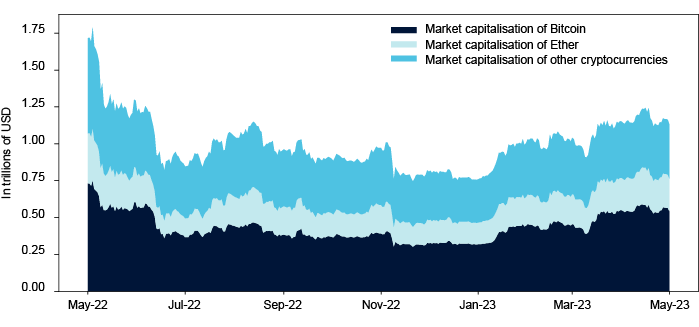

Developments in crypto-asset markets

Developments in crypto-asset markets have been turbulent over the past year. Value fluctuations have been pronounced (Chart 3.1), many systems have failed and a number of market participants have declared bankruptcy. In May 2022, the algorithmic stablecoin1 USD Terra collapsed, which at the time was the third largest stablecoin. Along with a broader market decline, this contributed to the financial difficulties faced by many crypto-asset investors in summer and autumn 2022, and subsequently resulted in their filing for bankruptcy protection. An example is the cryptocurrency exchange FTX, which collapsed in November 2022, along with a number of affiliates. One stablecoin (USDC), considered safe by market participants, has experienced turbulence and considerable breaches of parity as a result of problems at the US Silicon Valley Bank in spring 2023.

Volatility and negative events have primarily affected individual investors, particularly retail investors. Silvergate, a small US bank that offered banking services to the crypto industry, saw customers withdraw substantial deposits in January 2023.2 In March, it became known that Silvergate would discontinue its banking operations. A number of US banks have experienced problems this spring, and prices for some cryptocurrencies have subsequently risen.

The MiCA regulation targets a number of risk-generating activities related to crypto-assets, although coverage is not exhaustive. Such targeted regulation often fails to capture risk related to the newest technological developments and activities and can therefore be insufficiently resilient to developments and circumvention made possible by technological innovation. For example, MiCA does not cover a considerable amount of the developments in decentralised finance as the regulation’s primary focus is on centralised market participants.33

It is therefore important to take advantage of the potential of robust general regulations to reduce risk related to new developments (see "Ways to regulate crypto-assets" on ways to regulate crypto-assets). One lesson from the crypto-asset market turmoil in 2022 is that many types of activity may fall within the scope of general fraud regulations. These are often based on enforcement after the infringement has occurred (ex-post enforcement). For these to have an ex-ante disciplinary effect, it is necessary that participants perceive the likelihood of being detected as sufficiently high and that the sanctions provide sufficient deterrence. Enforcement will increase the disciplinary effect. The regulations in these areas are more relevant for other authorities than Norges Bank. Norges Bank could nevertheless contribute to such assessments.

At the same time, specific regulations should be developed further. Such specific regulations can be adapted to different risks associated with an activity, eg systemic risk, and contribute to more efficient allocation of responsibility for risks. Specific regulation can also facilitate more effective enforcement and increase the likelihood of infringement detection through follow-up by dedicated supervisory authorities. International collaborative arrangements are important in preventing market participants from adapting in order to circumvent regulation. In addition to the work on a common EU regulatory framework, many international organisations are contributing to such frameworks. The Financial Stability Board (2023) assesses the systemic risk related to decentralised finance and identifies the need for regulation.

The European Commission has ambitions to move forward in developing specific legislation that goes beyond MiCA in its current form, but the time this will take is uncertain. Some countries may also have different motivations for further development of a common specific regulatory framework in the EU, for example owing to national differences in how general regulations are enforced and the effectiveness of judiciaries. Countries may also have different motives for wishing to exploit specific legislation as a tool of industrial policy.

National strategy

An international regulatory framework is crucial. Nevertheless, the Norwegian authorities should assess whether to proceed more quickly rather than wait for international regulatory solutions. This may be due to national needs, gaps in international regulation and the fact that international standardisation takes time. As an example, an assessment can be made of how risk associated with decentralised finance should be managed by regulation until a common European regulatory framework is in place. It may therefore be appropriate for the authorities in Norway to discuss targets and measures that can be included in a strategy for crypto-asset regulation in Norway. The absence of such a strategy may provide more scope for private entities to influence Norwegian regulatory developments in an undesirable manner. Other regulatory conditions can also influence the scope of crypto-asset activity in Norway. Examples include regulations related to data centre operation, electricity taxes and other tax rules.

A national strategy requires cooperation among national authorities – not only financial authorities, but also consumer protection and judicial authorities. The Norwegian authorities should consider:

- whether initiatives for further national regulations are needed, and

- the scope for national rules provided by the EU legislation.

Norges Bank can contribute to such assessments and to regulation promoting responsible innovation.

Need for knowledge

Crypto-assets are a relatively new area of finance, where the economic, regulatory and research experience is relatively limited compared with many other areas of finance. This can contribute to poorly informed regulation and at the same time lead to regulation that is improperly based on research and analysis carried out or influenced by the industry.

At the same time, little is known about Norwegian entities’ crypto-asset exposures, attitudes and applications. Data from tax authorities and certain surveys from entities in the industry are available. Internationally, several central banks and other authorities have conducted surveys to increase knowledge about such conditions. Norges Bank will help to increase knowledge in this area by means of relevant analytical tools, analyses and the like. This could include analyses of crypto-asset holdings and transactions and surveys that identify user behaviour and risk.

Different authorities will benefit from professional cooperation and information exchange. Public authorities should also contribute to research in this area, both through funding and cooperation with academic institutions. Norges Bank is currently assessing whether collaboration with different academic institutions can help increase research-based knowledge about crypto-asset regulation.

Ways to regulate crypto-assets

Crypto-asset regulation can be implemented both by enforcing existing general regulations and by developing specific crypto-asset regulations.

General regulations

General regulations such as criminal and tort law cover many types of activity that carry risk. For example, general rules will cover fraud carried out in activities related to crypto-assets. General marketing rules can address deceptive marketing related to crypto-assets even if they are not covered by a financial regulatory framework.

General regulations are robust and cover many types of activity regardless of the way they are carried out. Robust regulation is particularly important as new types of services posing individual and societal risk can rapidly develop and grow.

Specific regulations

General rules are not necessarily sufficient to counteract the risk associated with crypto-assets. Specific regulations can fulfil various purposes. Some types of crypto-market activity fall under existing specific regulations. For example, issuance and trading in certain types of crypto-assets are covered by the regulations for issuance and trading in securities under securities regulations. In addition, there is a need for dedicated regulations for crypto-assets and associated activities. MiCA is an example of this.

29 Collective term for cryptocurrencies, stablecoins and tokens. Stablecoins are crypto-assets that aim for a stable value against a reference eg USD. See Norges Bank (2022a) for further definitions of terms.

30 Decentralised finance is financial products and services that are implemented in smart contracts and decentralised technology. Smart contracts are computer programs that automate services between parties according to predefined conditions. Examples of decentralised finance can be decentralised exchange platforms, loan platforms or platforms for trading in financial instruments.

31 See BCBS (2022).

32 See EPRS (2022). The EU Parliament endorsed the MiCA regulation on 20 April 2023 (see European Parliament (2023)).

33 For decentralised activities to fall outside the scope of the regulation, the activity must be provided in a fully decentralised manner without any intermediary (ee MiCA Preamble Recital 12a). Many services currently presented as decentralised without actually being so will therefore be covered by the regulation.

4. Central counterparties and margin calls

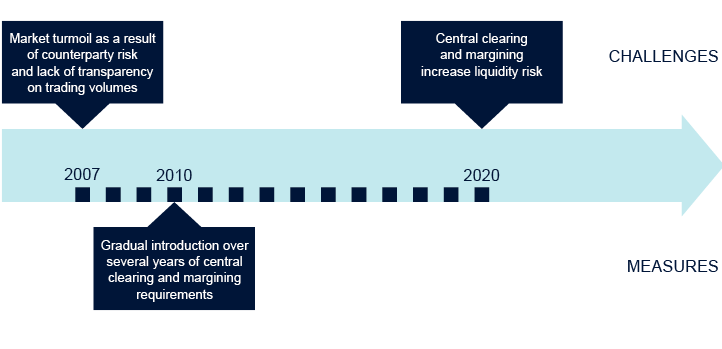

Since 2010, a number of jurisdictions have introduced central clearing and margining requirements for derivatives trades, which minimises the impact of a counterparty default. However, in recent years, large margin calls have led to liquidity problems for market participants in some countries. Measures to mitigate liquidity risks arising from margin calls are the focus of international efforts.

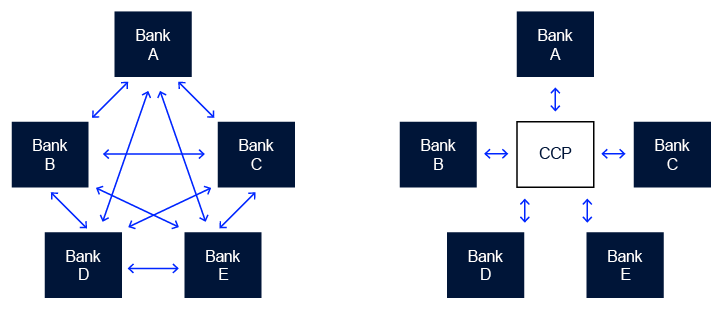

A central counterparty (CCP) interposes itself between counterparties to financial transactions, becoming the buyer to the seller and the seller to the buyer (Chart 4.1). This process is called “central clearing”. The use of CCPs may improve market function in periods of financial stress. Defaults by large financial institutions on derivatives contracts will have less serious consequences when they are handled by CCPs.