Executive Board’s assessment

The Financial Infrastructure Report is part of Norges Bank’s work to promote financial stability and an efficient and secure payment system in Norway. The Executive Board discussed the content of the Report on 27 April 2021.

Norges Bank supervises and oversees key financial market infrastructures (FMIs), issues cash and ensures settlement of interbank payments. At the same time, Norges Bank promotes change that could make the payment system more secure and more efficient. An efficient payment system carries out payment transactions swiftly, at low cost and tailored to users’ needs.

The Executive Board considers the Norwegian financial infrastructure to be secure and efficient. The Norwegian payment system has long featured standardised and user-friendly solutions, and the social costs of payments appear to be low compared with other countries. The operation of the financial infrastructure has been consistently stable.

The payment landscape is evolving, with internationalisation, new providers and new payment methods making their mark. At the same time, cyber threats are growing. These structural changes are the reason that Norges Bank is assessing whether measures are needed to enable the public to pay efficiently and securely in NOK also in the future. Key issues are related to cyber resilience, the real-time payment infrastructure, central bank digital currency (CBDC) and cash.

Threats to fundamental national interests and critical infrastructure are increasingly cyber-related. Over the past two years, there has been an acceleration of digital risk in Norway, with a marked rise in the number of serious incidents. Cyber attacks are used by various threat actors and may be a tool in wars and conflicts.

Cyber incidents are a potential threat to the financial system and financial stability. Globally there is broad agreement that resilience against cyber attacks in the financial sector must be strengthened. This requires extensive public-private cooperation, which has been a defining feature of the Norwegian payment system. Norges Bank and Finanstilsynet (Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway) are working together to introduce cyber resilience testing in accordance with the TIBER framework in Norway (TIBER-NO) to bolster the cyber resilience of the financial system. Critical functions to be tested and the entities responsible for them have been identified. Testing is expected to begin in 2023. TIBER-NO testing includes the sharing of experience with testing and therefore also involves collaboration with private entities.

A well-functioning real-time payment solution is a key component of an efficient payment system. Real-time payments are payments where the funds are available in the payee’s account seconds after the payment is initiated. Norges Bank has entered into formal discussions with the European Central Bank (ECB) on possible participation in the Eurosystem’s TARGET Instant Payment Settlement (TIPS) service. The primary objective is to facilitate the development of new real-time payment services for customers. Norges Bank is in the process of reviewing and assessing the TIPS service at a detailed level, including the technical setup, security, contingency arrangements and costs. This work will lead to a basis for deciding on a possible participation in TIPS, which safeguards Norges Bank’s requirements and the needs of other relevant stakeholders.

The international messaging standard ISO 20222 will be the standard for payment messages in Norway. ISO 20222 enables messages to contain more information and the information is structured in a way that better facilitates automated payment processing. Work to introduce ISO 20022 is ongoing at banks, Bits and Norges Bank. In the Executive Board’s view, it is important that payment infrastructure participants prioritise this work.

Crypto-assets are currently rarely used for ordinary payments. Other applications are experiencing strong growth. An example is decentralised finance, with services such as loans, derivatives and conversion between crypto-assets. The development of stablecoins, digital currencies intended to have a stable value against official currencies, plays an important role in decentralised finance and may help to give crypto-assets a greater role in ordinary domestic and cross-border payments.

There have been a number of initiatives to regulate crypto-assets internationally, including in the EU/EEA. Some of them address systemic risk, especially related to stablecoins. Geopolitical uncertainty and financial sanctions have highlighted the need for regulation in this area. Regulation can help realise economic gains from innovation and mitigate risk. Norges Bank is monitoring developments and will contribute to regulation that promotes responsible innovation.

Falling cash use and other developments in the payment system are the background for Norges Bank’s assessing whether the public should have access to a CBDC in addition to cash. The Bank’s research into CBDCs has reached a phase comprising experimental testing of technical solutions, while the purposes and consequences of introducing a CBDC are analysed further. The research will provide a basis for a decision on whether the Bank will take the next step and test a candidate solution.

Although cash usage is low in normal situations, cash still plays an important role in the payment system. Cash is ultimately the only alternative if electronic payment solutions should fail completely and is important for those that do not have the skills or opportunity to use digital payment solutions. For cash to be able to fulfil its functions, it must be available and easy to use. New amendments to the Financial Institutions Act clarify the banks’ obligation to enable their customers to make cash deposits and withdrawals. The amendments help to make cash more available.

Banks are responsible for cash contingency arrangements if the electronic payment systems fail. In the event of a larger-scale failure of societal infrastructure, Norges Bank is of the opinion that appropriate cash contingency arrangements need to be clarified, including the division of responsibility for back-up solutions. In Norges Bank’s view, this should be studied further in collaboration with relevant institutions.

Norges Bank has noted that some merchants do not accept cash payments. For cash to be easy to use, it is the Bank’s opinion that the right to pay cash should be clarified so that it cannot be contracted away by standard terms and conditions. And at the same time, the ability to impose effective sanctions should be in place for failure to comply.

In the 2022 Financial Market Report, the Norwegian government announced its intention to appoint a commission to assess the future role of cash in society before the end of this year. Norges Bank supports the creation of such a commission.

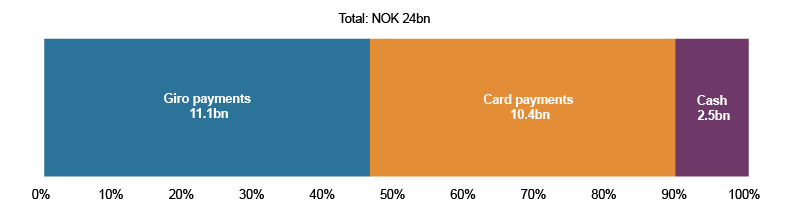

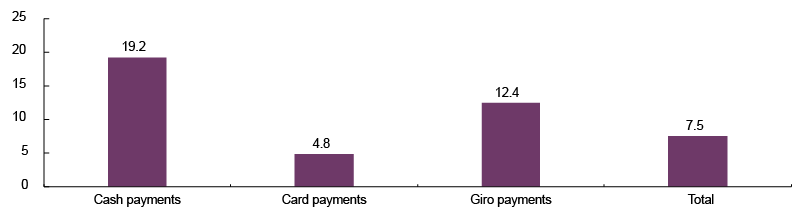

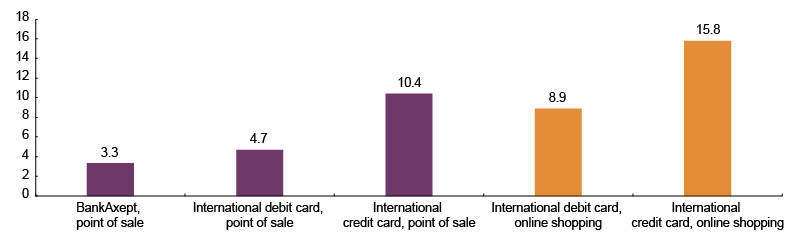

Norges Bank has recently surveyed the Norwegian payment system’s resource use. As a share of mainland GDP, this has decreased somewhat between 2013 and 2020. More payments are being made than before, and the unit cost per payment has therefore fallen. Card payments at physical points of sale have become cheaper. A significant increase in online shopping, which features a higher unit cost per payment than shopping at physical points of sale, pulls up total costs. Most bills are currently paid using automated solutions such as direct debit and e-invoicing. However, many bills are still sent on paper or as e-mail attachments. Manual processing means that paying such bills involves relatively high resource use. Transitioning to more automated solutions would save society considerable resources. At the same time, it is important that non-digital users have access to payment services that are tailored to their needs.

Norges Bank’s responsibilities

Norges Bank is tasked with promoting financial stability and an efficient and secure payment system.1 The Bank’s tasks in this regard comprise:

- Overseeing the payment system and other financial infrastructure and contributing to contingency arrangements.

- Supervising interbank systems.

- Providing for a stable and efficient system for payment, clearing and settlement between entities with accounts with Norges Bank.

- Issuing banknotes and coins and ensuring their efficient functioning as a means of payment.

As operator, Norges Bank ensures efficient and secure operating platforms and sets the terms for the services the Bank provides. As supervisory authority, Norges Bank sets requirements for licensed interbank systems. Through its oversight work, Norges Bank urges participants to make changes that can make the financial infrastructure more efficient and secure. An efficient payment system carries out payment transactions swiftly, at low cost and tailored to users’ needs.

The use of instruments in different areas will vary over time and be adapted to developments in the payment system and the financial infrastructure. Norges Bank is tasked with giving advice to the Ministry of Finance when measures should be implemented by bodies other than the Bank in order to meet the objectives of the central bank.

Financial infrastructure

The financial infrastructure can be defined as a network of systems, called financial market infrastructures (FMIs), that enable users to perform financial transactions. The infrastructure must ensure that cash payments and transactions in financial instruments are recorded, cleared and settled and that information on the size of holdings is stored.

Virtually all financial transactions require the use of the financial infrastructure. Thus, the financial infrastructure plays a key role in ensuring financial stability. The costs to society of a disruption in the financial infrastructure may be considerably higher than the FMI’s private costs. The financial infrastructure is therefore subject to regulation, supervision and oversight by the authorities.

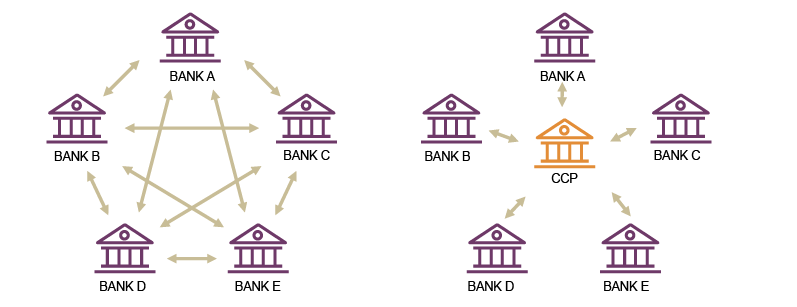

The financial infrastructure consists of the payment system, the securities settlement system, central counterparties (CCPs), central securities depositories (CSDs) and trade repositories.

Norges Bank’s supervision and oversight work

Norges Bank is the licensing and supervisory authority for the part of the payment system called interbank systems (Table 1.1). These are systems for clearing and settling transactions between credit institutions. If a licensed interbank system is not configured in accordance with the Payment Systems Act or the licence terms, Norges Bank will require that the interbank system owner rectify the situation. The purpose is to ensure that interbank systems are organised in a manner that promotes financial stability. Licensed interbank systems are shown in Table 1.1. Norges Bank may grant exemptions from the licensing requirement for interbank systems considered to have no significant effect on financial stability.

Oversight entails monitoring FMIs, following developments and acting as a driving force for improvements. This work enables Norges Bank to recommend changes that can make the payment system and other FMIs more secure and efficient. Even though Norges Bank oversees the payment system as a whole, individual systems are subject to regular individual oversight (Table 1.1).

Norges Bank assesses the FMIs that are subject to supervision and oversight in accordance with principles drawn up by the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI) and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO). The CPMI is a committee comprising representatives of central banks, and IOSCO is the international organisation of securities market regulators. The objective of the principles is to ensure a robust financial infrastructure that promotes financial stability.

A number of the FMIs that Norges Bank supervises or oversees are also followed up by other government bodies. The oversight of international FMIs that are important for the financial sector in Norway takes place through participation in international collaborative arrangements.

Finanstilsynet supervises systems for payment services. These are retail systems, which the public has access to, such as cash, card schemes and payment applications. Norges Bank’s oversight covers the payment system as a whole, including retail systems.

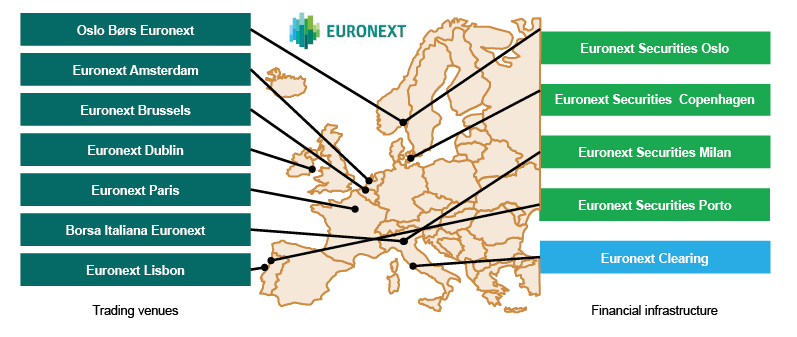

The EU Central Securities Depository Regulation (CSDR) imposes a number of tasks on Norges Bank which supplement Norges Bank’s responsibilities for overseeing Euronext Securities Oslo under the Central Bank Act. Finanstilsynet is the competent authority for Euronext Securities Oslo under the CSDR, while Norges Bank is a relevant authority.

A detailed description of the FMIs supervised or overseen by Norges Bank is provided in Norway’s financial system 2021.2

Definitions in the Payment Systems Act

Payment systems are interbank systems and systems for payment services:

Interbank systems are systems for the transfer of funds between banks common rules for clearing and settlement.

Systems for payment services are systems for the transfer of funds between customer accounts in banks or other undertakings authorised to provide payment services.

Securities settlement systems are systems based on common rules for clearing, settlement or transfer of financial instruments.

Table 1.1 FMIs subject to subject to supervision or oversight by Norges Bank

|

System |

Instrument |

Operatør |

Norges Banks rolle |

Andre ansvarlige myndigheter |

|

|

Interbank systems |

Norges Bank’s settlement system (NBO) |

Cash |

Norges Bank |

Supervision (Norges Bank’s Supervisory Council) and oversight |

Supervision: Norwegian National Security Authority |

|

Norwegian Interbank Clearing System (NICS) |

Cash |

Bits |

Licensing and supervision |

|

|

|

DNB’s settlement bank system |

Cash |

DNB Bank |

Licensing and supervision |

Licensing and supervision of the bank as a whole: Finanstilsynet and Ministry of Finance |

|

|

SpareBank 1 SMN’s settlement bank system |

Cash |

SpareBank 1 SMN |

Oversight |

Licensing and supervision of the bank as a whole: Finanstilsynet and Ministry of Finance |

|

|

CLS |

Cash |

CLS Bank International |

Oversight in collaboration with other authorities |

Licensing: Federal Reserve Board Supervision: Federal Reserve Bank of New York Oversight: Central banks whose currencies are traded at CLS (including Norges Bank) |

|

|

Securties settlement systems |

Euronext Securities Oslo’s central securities depository business |

Securities and cash |

Euronext Securities Oslo and Norges Bank |

Oversight |

Licensing and supervision of Euronext Securities Oslo: Finanstilsynet |

|

LCH’s central counterparty system |

Financial instruments |

LCH |

Oversight in collaboration with other authorities |

Supervision: Bank of England Oversight: EMIR College and Global College (including Norges Bank) |

|

|

EuroCCP’s central counterparty system |

Financial instruments |

EuroCCP |

Oversight in collaboration with other authorities |

Supervision: Dutch central bank Oversight: EMIR College (including Norges Bank) |

|

1 Cyber resilience of the financial infrastructure

Threats to fundamental national interests and critical infrastructure are increasingly cyber-related. Over the past two years, cyber resilience risk has increased with the number of serious incidents showing a marked rise.

Cyber incidents can affect financial stability if they affect one or more critical financial system functions or by affecting software, services or providers that many institutions rely on. In the Norwegian financial system, cyber incidents can spread quickly because of the high degree of operational interconnectedness. At the same time, the financial sector in Norway has established risk mitigation measures and collaborates effectively through venues such as Nordic Financial CERT (NFCERT).

Globally there is broad agreement that resilience to cyber attacks with the potential to threaten financial stability should be strengthened. Norges Bank is engaged in mitigating cyber risk in the financial system and, along with Finanstilsynet, is in the process of establishing testing of cyber resilience in Norway in accordance with the TIBER framework.

Threat landscape

Threats to fundamental national interests are increasingly cyber-related. Potential sabotage of critical infrastructure resulting from cyber attacks can have serious consequences. Substantial assets and obvious opportunities for financial gain make the financial sector an attractive target.

The number of serious cyber incidents has tripled since 2019.3 Foreign intelligence services are behind many of them.4 According to the Norwegian Police Security Service, the cyber attacks on the Storting (Norwegian parliament) in 2020 and 2021 were examples of very serious incidents.5 Other countries have found that state actors have the capacity to carry out sabotage with the aid of cyber attacks.6 Over time, there has been a trend whereby threat actors are becoming increasingly specialised and also buy services from one another.

Both parties are using cyber attacks as weapons of war in Ukraine. For instance, Russian cyber attacks have disabled satellite communication used by the Ukrainian army, electricity supply and the government’s website.

The sharp increase in ransomware attacks in recent years illustrates the potential for harm by digital sabotage.7 The attacks on Nordic Choice and Amedia in 2021 are examples of incidents in Norway. In other countries, the health services, police, fuel deliveries and food supplies are among those that have been affected.

The ransomware attack on Colonial Pipeline in May 2021 resulted in a stoppage over several days of the company’s fuel distribution to much of the US east coast and showed that cyber attacks on infrastructure can have serious consequences.8 In March 2022, the FBI sent out an alert that more than 50 businesses in 10 critical infrastructure sectors had been affected by RagnarLocker ransomware.9 This shows that ransomware attacks on infrastructure are widespread in the US, which can be an indication of such developments in Norway as well.

The SolarWinds incident in 2021, where software was infected and widely distributed, illustrates the potential for cyber attacks though supply chains. This type of attack is likely to be common in the period ahead.

Complex supply chains

New entrants are taking positions in and delivering services to the payment system. Global giants and newly established companies are delivering payment services to end-users, for example, on smart phone apps. More and more key payment system functions and services are being provided by global companies. ICT operations are increasingly being delivered via cloud services from centralised data centres. The security level of many of these large providers is high, but long supply chains increase complexity and dependencies.

How can cyber attacks threaten financial stability?

Characteristics of the financial system can potentially amplify and spread the consequences of a cyber attack through the system. In very serious cases, cyber attacks have the potential to threaten financial stability (Chart 1.1). Owing to extensive digitalisation and interconnectedness, the financial system in Norway is vulnerable to cyber attacks.

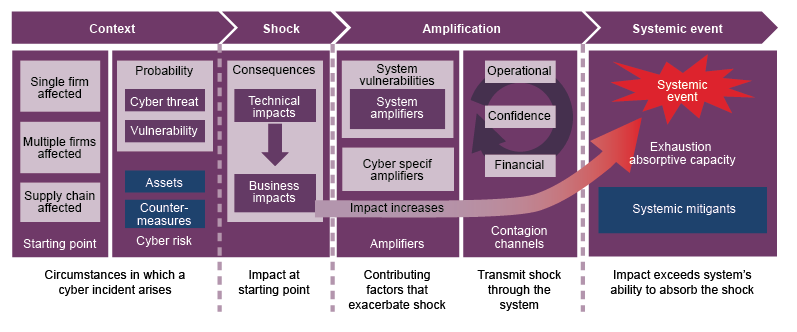

Chart 1.1: Path from a cyber incident to a systemic crisis

The chart shows how the impact of a cyber attack can be amplified through channels of contagion in the financial system. The consequences are normally limited to the businesses and value chains directly affected by the attack. The attack will initially be felt on a technical level, eg by putting ICT systems out of operation, and can quicky thereafter have business-related consequences.

The shock can be amplified through the financial system via dependencies and interconnectedness, aggravating its impact at both the operational and financial level and by weakening confidence in the system. A systemic crisis ensues if the impact of the attack exceeds the system’s ability to absorb the shock.

Measures to mitigate cyber risk

Each entity’s capabilities in preventing and dealing with attacks are the most important part of defence against cyber incidents. Industry collaboration is also important. In the Nordic countries a collaborative effort in the financial sector coordinated by NFCERT10, has been established to share information about vulnerabilities and incidents. The Financial Infrastructure Crisis Preparedness Committee (BFI) plays a key role in preventing and resolving crises and other situations that can result in serious shocks to the financial infrastructure.

There is increasing risk that a cross-border cyber incident could have a systemic global impact.11 Internationally there is broad agreement that financial sector cyber resilience should be strengthened. The potentially serious consequences for financial stability of a cyber attack increase the need for regulation and coordination.

Norges Bank is pursuing its efforts in this area by participating in Nordic and European collaborative arrangements for sharing information and developing methodologies for mitigating cyber risk in the financial system. An important measure in Norway is the introduction of the TIBER framework, TIBER-NO. TIBER-NO is a national adaptation of TIBER-EU, developed by the European Central Bank (ECB).12 TIBER tests simulate real attacks and provide greater insight into vulnerabilities for both the entity tested and for financial stability. A standardised testing programme ensures quality and comparability of experience with testing, also across countries.

Norges Bank and Finanstilsynet are collaborating on TIBER-NO and are in the process of establishing a “TIBER-NO Cyber Team” (TCT-NO) to administer and operationalise TIBER-NO. TCT-NO is to be organised at Norges Bank and is expected to be established before year-end 2022. Critical functions have been identified. Plans are being established for a separate body for experience sharing after TIBER testing in Norway, the TIBER-NO Forum, with its first meeting in 2022 Q3.

The collaboration with Finanstilsynet on TIBER-NO is an example of cooperation between key participants, which is an important characteristic of the Norwegian payment system. This cooperation has helped give Norway a payment system whose operations are stable, which is particularly important in contingency situations. Once TIBER-NO testing is launched, there are plans to share experience with testing between entities responsible for the functions being tested. A successful introduction of TIBER-NO therefore also involves collaborating with private entities.

Norges Bank’s cyber resilience requirements for operators of FMIs have become more stringent (see Norges Bank (2021b)). Operators are expected to conduct self-assessments of their level of maturity based on internationally recognised standards, and to take necessary action.

In 2020, the IMF performed an assessment of supervision and oversight of the cyber resilience of Norway’s financial sector as part of its review of the Norwegian financial system. In the IMF’s assessment, the Norwegian financial systems’ platforms for sharing information and threat intelligence and for dealing with attacks are mature and advanced. Regulatory and supervisory practices are generally adequate. Norges Bank is following up the recommendations, which are related among other things to the process for cyber resilience oversight, Norges Bank’s expectations of payment system operators, and reporting of systemically critical incidents.

3 See NSM (2022).

4 See NSM (2022).

5 See PST (2022).

6 See PST (2022).

7 See PST (2022).

8 See NSM (2021).

9 See FBI Cyber Division (2022).

10 Nordic Financial CERT (NFCERT) is a non-profit organisation in the Nordic financial sector. Its purpose includes sharing threat intelligence and information about vulnerabilities and assisting financial institutions will dealing with cyber attacks. See NFCERT (2022).

11 See ESRB (2021).

12 In 2018, the ECB published a framework for testing an entity’s ability to detect and respond to a cyber attack (Threat Intelligence-based Ethical Red Teaming (TIBER-EU)) (see ECB (2018)). The purpose of TIBER-EU is to enhance the cyber resilience of financial sector entities and promote financial stability.

2 Crypto-assets

New applications, risk and regulatory initiatives have drawn considerable attention to crypto-assets and associated products and services. The role of cryptoassets as means of payment outside of the crypto-asset market is still modest. The development of stablecoins may result in a greater role for crypto-assets in ordinary payments. The emergence of crypto-assets provides opportunities for innovation, but also carries risks to both individuals and society as a whole. Regulation can promote responsible innovation, which contributes to both realising societal gains and to mitigating risk. A number of international regulatory initiatives have been taken, including by the EU/EEA. However, many regulatory questions and decisions remain.

Developments in crypto-asset markets

Value fluctuations and the emergence of new products and services associated with crypto-assets have sustained interest in crypto-assets over the past year.

Glossary of terms

Crypto-assets: Collective term for cryptocurrencies, stablecoins and tokens (see below). Often used in the regulatory contexts of assets that are represented with cryptographic codes in distributed ledgers.

Cryptocurrencies: Units in a ledger or data system designed to be operated in a decentralised manner. Ledgers are often referred to as blockchains. The units are accessible via cryptographic keys. The system itself can be referred to as a DLT (distributed ledger technology) system, while the ledger units are cryptocurrencies.

Smart contracts: A smart contract is a computer programme that automates exchanges between entities according to pre-defined conditions. The term is often used to describe programmes in a DLT system.

Tokens: Assets in a DLT system, often issued under a smart contract. Accessible via cryptographic codes. Tokens can be fungible (mutually interchangeable) or non-fungible (Non-fungible token – NFT). The latter represents a unique value, such as a digital piece of art, or items in a gaming ecosystem. Such NFTs can also represent other traditional assets, such as securities and real estate.

Decentralised finance: Financial products and services implemented using smart contracts. This may include decentralised exchange services, lending platforms or platforms for trading financial instruments.

Stablecoins: Cryptocurrencies that aim to preserve a stable value against a benchmark (for example USD) through a stabilisation mechanism. They are often implemented as tokens in a smart contract in a DLT system. They can be secured, for example, through external assets managed by an external entity, external crypto-assets and/or algorithms that impact supply and demand.

Web3: A vision for a more decentralised internet where users own their own data and where blockchains make users less dependent on central operators. One type of Web3 application is Metaverse, which refers to virtual worlds (gaming etc) or a network of such worlds.

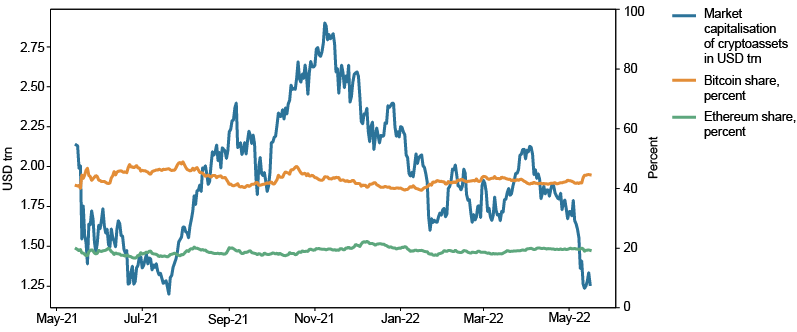

The total value of crypto-assets has also been highly volatile over the past year. The Bitcoin (BTC) market share has remained around 40%, while Ethereum (ETH) has remained around 20% (Chart 2.1). Ethereum has been a key ecosystem for the development of a number of new products and services including decentralised finance, non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and Web3 applications in general.

Chart 2.1 Market capitalisation of cryptocurrencies and shares for the two largest.

New cryptocurrency systems have emerged that can compete with Ethereum, such as infrastructures for decentralised finance. Examples include Solana and Cardano. The value of these systems’ currencies has risen, although with considerable volatility. Chart 2.2 shows developments in the value of different crypto-assets over the past year as a percentage of the value at 1 May 2021.

Chart 2.2 Price developments for selected cryptocurrencies. Index, 1 May 2021 = 100.

There is reason to believe that speculating on price movements in certain crypto-assets can largely explain the volatility. A survey conducted by Arcane Research and EY shows that interest also increased among the general public in Norway.13 The survey shows that approximately 420 000 Norwegians hold crypto-assets, which is a 3% increase on the year before. At the same time, developments suggest that investment behaviour is more diverse than merely speculating on cryptocurrency volatility. This applies to both institutional investors and the mass market.

Highly correlated developments in the value of several crypto-assets may indicate that investors consider cryptocurrencies to be substitutable investments. Analyses also show a correlation between crypto-asset prices and prices for other assets.14 This may indicate a more general trend where crypto-assets follow broad market fluctuations. This correlation can also increase the importance of crypto-assets for financial stability.15 The financial stability impact of crypto-assets is discussed further in Norges Bank (2021b).

Through their holdings or acquisitions, institutional market participants have invested in crypto-asset service providers.16 In September 2021, it became known that Mastercard had acquired the company Ciphertrace, which among other things, provides analytical services for uncovering criminal transactions in cryptocurrency systems. In January 2022, it became known in Norway that the media company Schibsted had invested in the trading platform Firi.17 Globally, certain financial institutions have acquired or invested in crypto custody service providers.18 Companies that provide services and products related to decentralised finance, NFTs, Web3 and the metaverse, have attracted venture capital.19

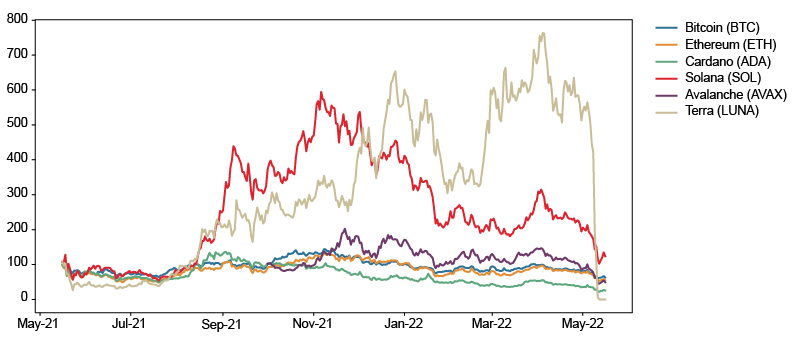

New products and services have also attracted mass market users. Analyses show that NFTs are primarily traded in the mass market.20 Chart 2.3 shows developments in market value of crypto-assets that are used on decentralised finance platforms (often referred to as “total value locked” – TVL). The Arcane Research and EY survey discussed above shows that 10% of Norwegians who hold crypto-assets (ie approximately 1% of the Norwegian population) participate actively in decentralised finance and NFT-related activities.

Chart 2.3 Developments in market value of crypto-assets locked to decentralised finance (DeFi)21

Stablecoins play an important role in crypto-asset trades particularly in markets that do not offer direct trading with deposit money. Stablecoins also play a particularly important role as liquid assets and unit of account in Desentralised Finance.

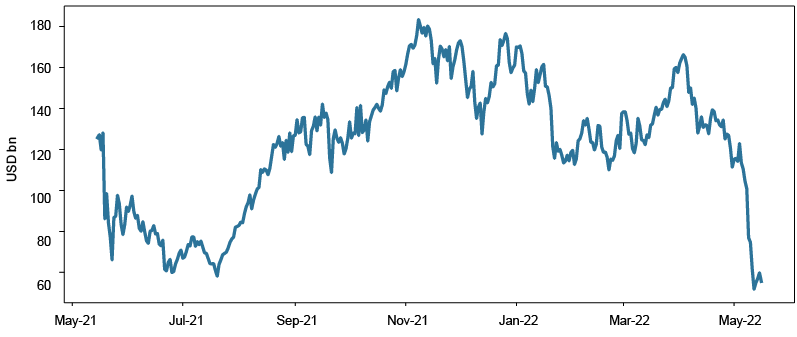

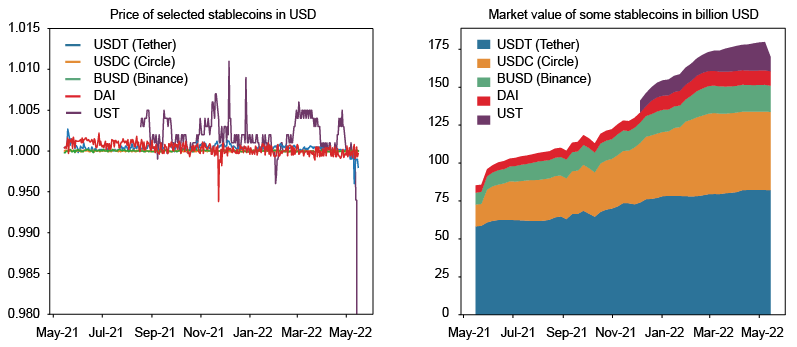

Stablecoins can be collateralised in different ways that can involve very differing degrees of stability (see box: Glossary of terms). Chart 2.4 illustrates the price of some stablecoins designed to some extent to be stable against USD. The chart shows that the stability of stablecoins can vary. The stablecoin USDC, which is considered to be relatively well-collateralised, has thus far been more stable than USDT, where the value of the assets intended to stabilise it is more uncertain. USDC has so far shown more stable price developments than BUSD, which is a secured stablecoin that is especially used in connection with services offered by the company Binance. DAI is a more decentralised stablecoin that is also securitised with cryptocurrencies with automatic liquidity mechanisms. DAI has remained relatively stable, although developments indicate that such securitisation may have a pronounced impact on stability. One stablecoin that has grown particularly during 2022 is UST, which is an algorithmic stablecoin built into the Terra cryptocurrency system. The stability hinges on the cryptocurrency unit LUNA in the system absorbing USTs volatility.22 As can be seen in the chart, UST has been less stable than the other stablecoins mentioned. The value of UST collapsed in the beginning of May 2022 and over the course of a few hours the price dropped down to USD 0.7, only to fall further.

Chart 2.4 Volatility and market value of selected stablecoins

Source: Tradingview.com

Many stablecoins have depreciated quickly and collapsed, particularly those that are stabilised solely by algorithms. Some stablecoins that have remained stable have yet to be exposed to a significant stress situation that could challenge their stability. The lower part of Chart 2.4 shows developments in market value in USD for the same three stablecoins and thus the quantity of issued units since they are USD-denominated. The developments illustrate the rise in demand for stablecoins.

Crypto-assets continue to play a modest role as a means of payment beyond the crypto ecosystem. One exception is El Salvador, which recognised Bitcoin as legal tender in parallel with USD in September 2021. This means that commercial entities have an obligation to list prices and receive payment in Bitcoin. In this regard, El Salvador has developed a national system for Bitcoin-denominated payments. The IMF has pointed out potential negative economic consequences of introducing Bitcoin as legal tender 23 Other countries have introduced specific legislation that will facilitate the use of crypto-assets for payments. The Central African Republic has introduced legislation similar to El Salvador’s.

Many stablecoins are intended for use as means of payment in the traditional economy and are being increasingly used in certain segments, for example remittances. Both technical and regulatory barriers prevent the use of stablecoins in traditional payments. Since stablecoins are often implemented as tokens on open blockchains, capacity constraints and fees in the blockchain limit the appeal of such stablecoins for retail payments. New scaling solutions can mitigate this problem in the future.24 The regulatory barriers are discussed in more detail below.

Risks and regulation

Crypto-assets and their underlying technology may result in gains for the financial system and offer new uses. At the same time, the emergence of crypto-assets and related services may entail risk for both individuals involved and for society. Regulation can promote responsible innovation that contributes to both realising gains and to reducing risk.

Globally, there is an extensive debate on the regulation of crypto-assets, in which the authorities, business sector interests and academia are taking part. For many types of regulation, international coordination and cooperation will be necessary to achieve desired effects. In other areas, national regulations may be more appropriate for addressing national priorities and needs. Norges Bank takes part in the development of international regulations through participation in certain relevant collaborative bodies and helps assess the need for specific regulations in Norway.

Norges Bank (2021b) has discussed a range of regulatory initiatives in the area of crypto-assets. These initiatives have evolved further. The European Commission’s proposed Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCA25) has been debated by the Council and the Parliament and is therefore closer to implementation.26 This regulation is designed to promote innovation, while also addressing matters including consumer protection, market integrity and financial stability. Member states are given some time to implement EU regulations so that there will still be some time remaining before the regulation could enter into force.

New regulatory initiatives are emerging in parallel with those that already exist.27 For a number of years, financial regulators across the globe have warned against investing in crypto-assets. Such warnings are about to be supplemented by more concrete instruments. MiCA includes information requirements for crypto-asset service providers and makes providers liable for misstatements. In many parts of the world, separate regulations for the promotion of crypto-asset services are currently being prepared to protect consumers from uninformed risk-taking and from being misled.28 Such regulations supplement general rules on information integrity. For the US, President Biden has signed a March 2022 executive order requiring a number of agencies to examine the need for crypto-asset regulation.29

Over the past year, certain areas have attracted particular attention from a risk and regulatory perspective: the significance of crypto-assets for financial stability, energy use related to certain cryptocurrencies, regulation of and liability for participants in crypto-asset systems and the ability of crypto-assets to circumvent sanctions resulting from the war in Ukraine. For an assessment of the significance of crypto-assets for financial stability and relevant regulations in that regard, see Norges Bank (2021c). In this consultation response, different channels of systemic risk were discussed: the crypto-asset exposures of financial institutions and financial investors, mass liquidation of assets backing stablecoins in the event of a loss of confidence, and disruptions (including operational or financial) to crypto-asset systems with major roles in the payment system.

Energy consumption

One issue that has attracted considerable attention is the energy consumption associated with certain decentralised mechanisms for validating transactions, particularly so-called proof-of-work, which is used for Bitcoin (see box: Energy consumption associated with Bitcoin).

Energy consumption associated with Bitcoin

Cryptocurrencies have a decentralised design. This means that system participants compete to validate new transactions and propose blockchain updates. The reward is new Bitcoin and/or transaction fees in Bitcoin. This activity is often referred to as “mining”. Miners only receive rewards if their proposed updates are chosen by future users as a basis, so that they become part of the ledger. The reward system gives miners the incentive to only add valid transactions and are therefore essential for the system’s self-regulation. The mechanism ensures that users agree on a single common ledger, even if there is no single entity responsible for ledger maintenance.

To prevent users’ updates from overcrowding the network, they can be linked to a scarce resource. In the Bitcoin network, this is energy. Proof must be provided of a certain amount of energy expended to solve cryptographic codes with raw computing power (“proof-of-work”) in order to validate. Other cryptocurrencies operate with mechanisms that are less energy-intensive. One example is the so-called proof-of-stake mechanism, whereby a user offers some of their own cryptocurrency units as collateral to propose transaction validations so that new units are added to the ledger.

For Bitcoin, the verification mechanism entails the use of large amounts of energy by computers to solve cryptographic problems with raw computing power in order to validate. A consequence is that the higher the value, the higher the profitability of energy and equipment use in competing. Different energy sources generate different projections for electricity consumption and associated emission volumes. Studies from the University of Cambridge show that Bitcoin mining today may account for as much as 0.5% of the world’s electricity consumption. In addition, this activity leads to enormous amounts of electronic waste.1

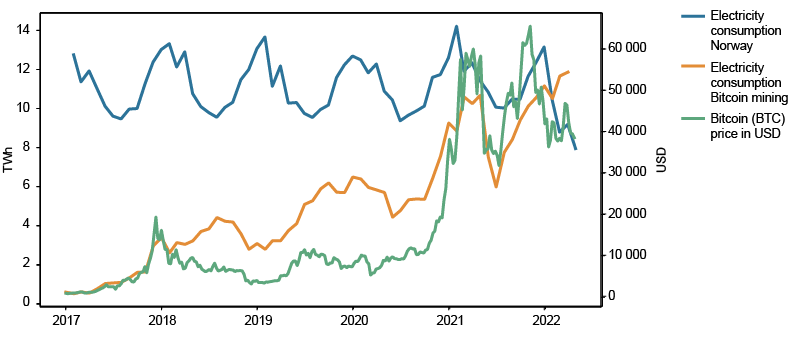

Chart 2.5 shows projections for monthly Bitcoin energy use globally compared with in Norway. Energy consumption appears to correlate with Bitcoin prices, reflecting the fact that higher prices increase the gains of participating in validation.

Chart 2.5 Electricity consumption in Norway and Bitcoin validation

1 See de Vries and Stoll (2021).

In summer 2021, China introduced a ban on cryptocurrency validation. Since a high share of the validations of, inter alia, Bitcoin had until then been conducted in China, the ban had a temporarily pronounced impact on Bitcoin energy consumption (Chart 2.5). However, this consumption rebounded rather quickly owing to increased mining activity in other countries.

In November 2021, the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority together with the environmental authorities proposed a ban on energy-intensive validation mechanisms for cryptocurrencies in the EU, as an instrument for compliance with the Paris Agreement.30 The draft MiCA regulatory framework initially contained a comprehensive ban on cryptocurrencies with energy-intensive validation mechanisms. After consideration by the ECON Committee in the European Parliament in March 2022, the proposal was modified so that by 2025, the European Commission must develop rules for the inclusion of cryptocurrency validation in EU taxonomy for sustainable activities.31 Some countries have introduced national bans owing to domestic effects on the electricity market.32 In the literature different proposals are provided for how institutional investors can address the environmental impacts of their energy consumption, and for taxation principles in carbon compensation.33

Basically, it is the market's role to allocate resources. This also applies to resources that are used to validate cryptocurrency transactions. However, various forms of market failure can prevent markets from allocating resources so that they provide the greatest possible benefit to society. Cost-benefit analyses can shed more light on the regulation of validation methods. In such an analysis, consideration should be given to whether any gains from cryptocurrencies can be achieved with less energy-intensive methods. In general, it can be demanding to compare the societal benefits of different purposes of electricity consumption.

Regulation and liability for participation in distributed ledger systems

There is an ongoing debate about how cryptocurrencies can be regulated methodically. The debate gives particular focus to regulatory challenges tied to the decentralised design of the systems.34 The main approach to crypto-asset regulation so far has been the regulation of different participants which serve as gatekeepers for access to crypto-assets, such as trading venues, custodians and payment service providers offering crypto-asset related services. Financial regulatory principles often serve as the inspiration for such crypto-asset regulation. Some have criticised this approach, citing the crypto-asset and ancillary service applications that are unsuited to financial regulatory principles.35

Centralised elements related to the issuance of crypto-assets are also suitable for regulation. For example, the pre-sale of a cryptocurrency under development can be subject to the same rules that apply to the issuance of securities. The MiCA regulatory framework discussed above regulates issuers of crypto-assets, including stablecoins.

One challenge is formulating rules and regulations that make participants accountable and gives them incentive to take societal considerations into account in the operation of crypto-asset systems. Certain international regulatory initiatives have been more directly aimed at participants of such systems. Different bans on certain validation mechanisms, for example owing to environmental considerations, regulate participants directly. In the US, a new infrastructure bill has been proposed that includes imposing tax-reporting requirements for cryptocurrency brokers.36

Self-regulation of distributed ledger systems and the competition between the systems are not sufficient for addressing societal considerations. The primary objective of self-regulation is to make the systems secure and attractive and does not necessarily provide participants with incentives for designing the systems so that they address societal considerations such as environmental considerations, crime prevention and financial stability37.

At the same time, the decentralised design presents challenges related to the regulation of participants that provide services in the systems, such that they promote societal considerations. Systems are implemented as open source code, with a multitude of developers spread across the globe, performing fragmented tasks. Services, such as the validation of transactions, are performed in a decentralised manner by “nodes” that are spread out across the globe and designed so that no single node can impact the outcome alone.

However, a decentralised design is no guarantee of actual decentralisation. More or less hidden power structures can have a substantial impact on the system.38 If this is the case, it would be natural for influential participants to be held liable for their behaviour.

If a system is actually decentralised, there are still opportunities to hold the systems and participation in them legally liable (see box: Legal liability of decentralised systems and participation in them).39

Norges Bank is assessing how liability of decentralised systems for crypto-assets and participation in them can reduce risk in Norges Bank’s areas of responsibility, including financial stability.

Legal liability of decentralised systems and participation in them

One method of holding desentralised systems and participation in them legally liable is to open up new forms of organisation that can be held legally liable. Some participants emphasise that certain systems can be characterised as so-called decentralised autonomous organisations (DAO), which from a regulatory perspective, can be assigned a legal person status on par with firms and other legal entities. With such systems given legal person status, they can also be assigned liability. If the systems are to be held liable in this manner, clarification will be necessary of how the organisation (the legal person) will be represented externally (eg in legal and regulatory contexts), and of capital provisioning to cover financial obligations. Certain jurisdictions are experimenting with such organisational structures. Industry interests have proposed rules that would make it possible for such organisations, in line with firms, to benefit from limited liability while also wholly or partially relieving members of liability.1 Such rules could promote innovation but also allow for greater risk taking and thus create challenges for responsible innovation.

Another approach is individualising liability by drawing on established liability principles for participants in composite systems that fully or partly work for a common organisation.2 This can be referred to as distributed, or network, liability and entails participants that are either fully (jointly and severally) or proportionally (pro rata) liable for their contributions to the system/network. The individual’s liability can be impacted by contributions to/influence over the system and system-related risks and rewards etc. Modern network analyses can help provide information on such influence. This approach to liability may be simpler to implement than creating new forms of organisation. This type of liability will not require substantial legal reform and can be based on established legal principles. The introduction of this approach to liability for cryptocurrency system participants is still in the research and discussion phase.

Use of crypto-assets to circumvent international sanctions

Cryptocurrencies have also received considerable attention in connection with the war in Ukraine. When the war started, the value of crypto-assets fell considerably, in line with many other assets, but later rebounded. The ECB was among the first to point out the need for regulation to counteract the use of crypto-assets to circumvent sanctions aimed at Russian entities. The US and other countries have since echoed the same need. Financial regulators in the US, the UK and the EU, among others, have emphasised that sanctions must be followed up by market venues and other crypto-asset market participants.

The use of crypto-assets to circumvent sanctions raises a number of questions. Crypto-assets can be used as an alternative store of value or an alternative payment system for both persons that are directly sanctioned and those who are not, but who do not have access to traditional payment systems because of sanctions. The ability of crypto-assets to circumvent sanctions depends on regulations in both the countries that impose sanctions and the sanctioned countries. In countries that impose sanctions, it is possible to regulate users and third parties by also excluding certain users and banning sales of “blacklisted” cryptocurrency units.40 For sanctioned countries, crypto-assets can contribute to capital flight and reduced governance and control. For such countries, facilitating the use of crypto-assets to circumvent sanctions is therefore not necessarily attractive. Developing alternative payment systems based on traditional technology to compete with SWIFT and international card companies may appear more attractive for maintaining governance and control. Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) can also be an alternative.

There are a number of interfaces between the war in Ukraine and crypto-assets. Both Ukrainian authorities and volunteer organisations have permitted the use of crypto-assets to support both military and civilian operations. This includes direct crypto-asset donations but also the use of crypto-asset systems for inter alia the issuance of NFTs to fund military and civilian activity.

Norges Bank is monitoring how the war in Ukraine is impacting the use of crypto-assets and the degree to which these developments affect risks and the need for regulation.

13 See Arcane Research and EY (2022).

14 See Adrian and Weeks-Brown (2021).

15 See Adrian et al (2022).

16 See The Block (2021).

17 See NTB Communication (2022).

18 See The Block (2021).

19 See The Block (2021).

20 See Chainalysis (2021).

21 Market value is measured based on the value of the crypto-asset that is ‘locked in’ on DeFi platforms (Total value locked – TVL).

22 In simplified terms, this means that the user can extract or delete UST with LUNA as if UST were worth USD 1. This means that if the price of UST is over USD 1, the user has an incentive to extract UST by deleting LUNA as they can sell UST for more than USD 1. Conversely, if the price of UST is under USD 1, the user has an incentive to delete UST and issue LUNA as they then receive LUNA as if UST was worth USD 1. This should have a stabilising effect on UST by adjusting supply and demand. Terra has in any case decided to supplement this stabilising mechanism by building up reserves in other crypto-assets. When UST collapsed in the beginning of May 2022, the price of both LUNA and UST fell, and LUNA was not able to absorb the volatility in UST. The issuers attempted to liquidate some of the Bitcoin reserves without any noticeable effect other than a fall in Bitcoin prices.

23 See Adrian and Weeks-Brown (2021) and IMF (2022).

24 These may be new cryptocurrency systems that are more scalable or so-called layer 2 solutions that can be placed on top of cryptocurrency systems in order to increase capacity.

25 See European Parliament (2022a).

26 For progress, see European Parliament (2022a).

27 See Ferreira and Sandner (2021) provide an overview of different regulatory initiatives in the EU.

28 See for example HM Treasury (2022).

29 See the White House (2022).

30 See Finansinspektionen (2021).

31 See European Parliament (2022b).

32 An example is Kosovo (see Reuters (2022)).

33 For example, see FSBC (2021).

34 For a discussion of cryptocurrency regulation, see Østbye (2021).

35 See eg Chiu (2021).

36 See Bloomberg (2021).

37 See Østbye (2021).

38 See Walsh (2021).

39 See Chiu (2021).

40 In cryptocurrencies, it is possible to track transactions through registry addresses, and certain addresses can be sanctioned. This may be more difficult for cryptocurrencies with enhanced anonymity characteristics, and this may explain a certain price and turnover growth of such cryptocurrencies. The use of such cryptocurrencies can also be counteracted by regulation.

3 Central bank money

At present, most payments are made using bank deposits, ie money created by banks. Norges Bank issues central bank money in the form of cash. Norges Bank is considering whether to supplement the cash used by the general public with a central bank digital currency (CBDC) to ensure an efficient and secure payment system and confidence in the monetary system.

3.1 Cash

The share of cash payments fell to a historically low level during the Covid-19 pandemic, increasing resource use per cash payment. Cash has a number of important characteristics that help to ensure that the payment system is efficient and secure. For example, cash helps prevent financial exclusion and is the only means of payment if the electronic payment solutions should fail completely. These characteristics are still vital, even if cash usage in normal situations is low.

Recent amendments to the Financial Institutions Regulation will help to safeguard the availability of cash now and in the future. Norges Bank is of the opinion that it should be clarified what is considered appropriate cash contingency arrangements, including the division of responsibility, in situations with a more widespread failure of critical infrastructure, also beyond the electronic payment systems. There is also a need for clarification of the payment situations in which the buyer may demand to pay cash.

In the Financial Market Report 2022, the Government announced plans to establish a commission in the course of the year to assess the future role of cash. Norges Bank supports the establishment of such a commission.

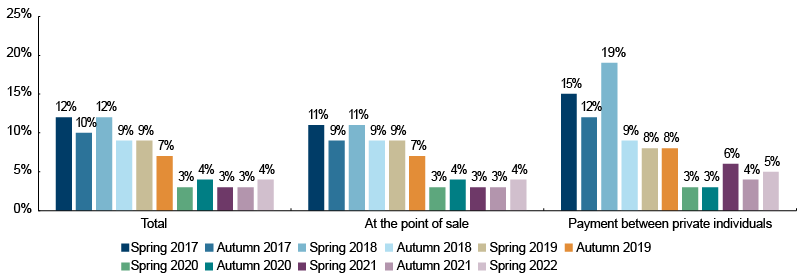

Cash usage has declined over a long period and fell further during the pandemic. Norges Bank’s surveys of private individuals show that around 4% of respondents used cash to make their most recent payment (Chart 3.1). However, information from other sources suggests that cash usage may be higher (see Section 6). Cash usage may also vary by merchant type and population segment. For example, in the grocery trade, cash usage may be higher than the data in the chart suggest.

Chart 3.1 Cash usage as a percentage of payment types Number of payments

Costs and benefits

Because cash usage has fallen substantially and a large proportion of the costs are fixed, the social costs per cash payment have risen (see Section 6 for details). At the same time, cash has characteristics that help to ensure a secure and efficient payment system. Many of these characteristics are of such a nature that they will continue to be important even in the face of falling cash usage.

Cash contributes to preventing financial exclusion in that it gives those who lack the skills to use electronic payment methods or are without access to them the opportunity to pay. Surveys of payment patterns show that cash is used more by the elderly and by immigrants, for example.

Electronic contingency arrangements are the first line of defence if electronic payment methods fail. Nevertheless, cash still plays an important contingency role if the electronic payment methods fail (see box: Stronger contingency arrangements for POS terminals). The Norwegian Directorate for Civil Protection (DSB) recommends that Norwegian households hold some cash as a contingency reserve. After major events, it has been noted that cash withdrawals increase. After the pandemic-related lockdown of Norway in March 2020, cash withdrawals from Norges Bank rose, and households’ average cash holdings increased before falling back somewhat (see Norges Bank (2020)). The amount of cash in circulation increased slightly also after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Furthermore, cash is without credit risk, and users’ ability to convert between bank deposits and cash underpins confidence in bank deposits. In addition, cash is legal tender. If the parties to a transaction do not agree on which means of payment to use, legal tender status ensures a reliable alternative. Cash is also an alternative that gives users a choice and promotes competition.

For cash to fulfil its role in the payment system, it must be available and easy to use.

Cash services – availability

Under Section 16-4 of the Financial Institutions Act and Section 16-7 of the Financial Institutions Regulation, banks have an obligation to ensure customers access to cash both in normal situations and if the electronic payment systems fail. In recent years, a number of ATMs, cash deposit machines and bank branches have been closed. However, the general public’s overall access to cash services has been strengthened, as a result of the Vipps in-store cash service (see broader discussion in Norges Bank (2021b)). At 16 March 2022, the service encompasses 90 banks and more than 1400 retail outlets across Norway. There are still shortcomings and vulnerabilities associated with the provision of cash services. Norges Bank has previously pointed out shortcomings and vulnerabilities regarding the ability of business customers to make cash deposits and that cash services are increasingly being channelled through the Vipps in-store cash services, which depends on functioning POS terminals and other electronic systems.

Contingency arrangements for POS terminals have recently been strengthened (see box: Stronger contingency arrangements for POS terminals). The strengthened contingency arrangements for POS terminals do not include cash withdrawals.

Stronger contingency arrangements for POS terminals

Bits has worked to strengthen POS terminals’ contingency arrangements. Since December 2021, several grocery chains, pharmacies and petrol stations have an improved backup solution, which will now function for seven days rather than only a few hours as previously. The backup solution will function when underlying systems or communication with these systems are not working but requires a functioning POS terminal. The improved backup solution will give retail chains and terminal providers more time to rectify problems before households will need to pay cash, which would put pressure on the cash infrastructure. Even so, there might be increased pressure on other parts of the cash infrastructure, since it will not be possible to withdraw cash via POS terminals when the backup solution is in use.

It is important that cash is also available in case the electronic contingency arrangements fail. In such situations cash will be needed by both those who are always dependent on cash and those who are usually able to use electronic means of payment.

It is also important to find efficient ways to ensure the availability of cash services so that costs are reasonable relative to the benefits. As a part of this, it is essential to clarify the scope of the banks’ responsibilities.

In September 2021, the Ministry of Finance circulated amendments to the Financial Institutions Regulation for comment. The amendments were approved by the Ministry of Finance on 5 April 2022 and enter into force on 1 October 2022. The amendments make clear that “each bank shall enable its customers to deposit and withdraw cash, either under the auspices of the bank itself or through an agreement with other cash service providers”.41

Norges Bank supported the regulatory changes.42 At the same time, in Norges Bank’s opinion, further clarification of banks’ obligation to ensure satisfactory cash services for their customers is needed. This clarification should pertain to both functionality and geographical availability and consider the different needs of private individuals and businesses. Furthermore, it is the Bank’s view that sanctions for noncompliance must be clearly defined.

Banks may take into account the risk-mitigating effects of electronic contingency solutions in designing their cash contingency arrangements (cf Section 16-7 of the Financial Institutions Regulation). It has not been specified how banks are to do this. In Norges Bank’s opinion, there should be established objective and verifiable criteria for how banks can consider the risk-mitigating effects of electronic contingency solutions in designing their cash contingency arrangements.

Banks are responsible for cash contingency arrangements if the electronic payment systems fail. In the event of a larger-scale failure of societal infrastructure, appropriate cash contingency arrangements need to be clarified, and the division of responsibilities for backup solutions. Key questions are: When is it acceptable and reasonable for banks not to give their customers access to their money and how can customers’ need to pay for goods be secured? This work requires collaboration among relevant government bodies, the banking industry and other entities, if necessary. Norges Bank will follow up these questions further.

Cash services – ease of use

For cash to be a real payment alternative, the public must have the ability to pay cash. Norges Bank has noted that some merchants do not accept cash payments. Norges Bank is of the opinion that consumers’ right to pay cash should be clarified to prevent individual businesses from unilaterally stipulating in their standard terms and conditions that the right to pay cash does not apply when they offer goods and services to the public. In addition, it should be clarified which payment situations are not covered (such as eg online shopping) at the same time, that the possibility to impose effective sanctions should be in place for failure to comply.

In the proposition for a new Financial Contracts Act in 2020, the Ministry of Justice and Public Security, stated that there is a need to look at whether the current rules on the right to pay in legal tender are appropriate. The Ministry of Justice and Public Security is in the process of looking more closely at how the right to pay cash can be strengthened, including what clarifications should be made in the legislation (see Financial Market Report 2022).

In the Financial Market Report for 2021, Finanstilsynet proposed that a public commission assess the future role of cash, and how the needs of various customer groups for cash services can be accommodated in the most efficient way possible. In its deliberations on the Report, the Storting made a formal request of the Government to appoint a public commission to assess the future role of cash. The Government announced in the Financial Market Report for 2022 that it intends to appoint such a commission in the course of 2022. Norges Bank supports the establishment of such a commission.

41 Regulation to amend the Financial Institutions Regulation (in Norwegian only). https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/forskrift-om-endring-av-finansforetaksforskriften/id2907346/

42 See Norges Bank (2021c).

3.2 Central bank digital currencies

Norges Bank’s research into central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) is in its fourth phase, which consists of experimental testing of technical solutions and an analysis of purposes and consequences of introducing a CBDC. This work will provide a basis for deciding whether Norges Bank will test a candidate solution.

A CBDC is a digital form of central bank money denominated in the official unit of account for general purpose users, ie a digital version of cash. So far, only a few central banks have introduced or are in the process of introducing a CBDC. Many central banks are now devoting considerable resources to exploring a potential CBDC. In 2021, the Eurosystem announced the launch of an investigation phase of the digital euro project. In the UK, a taskforce chaired jointly by the Bank of England and the Treasury has been established to study the issue. Central banks in the US, Canada, Sweden, China and elsewhere have intensified their efforts on CBDCs, as have international organisations such as the IMF and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). The BIS Innovation Hub has been established to experiment with ways in which new technology can strengthen the financial system, with CBDCs as a main focus.

CBDCs can take several forms with different characteristics, depending on its purpose. The purpose of and need for a CBDC depend on a country’s economic and financial structure. For example, assessments of financial inclusion as a purpose of a CBDC will depend on the extent to which the population already has access to payment services.

Norges Bank’s research

For Norges Bank, the paramount question is whether introducing a CBDC is an appropriate measure for promoting an efficient and secure payment system and confidence in the monetary system. The purpose of and previous work in researching CBDCs are discussed in detail in Norges Bank (2021b) and Norges Bank (2021e).

In 2021, Norges Bank decided to continue its research into CBDCs. In this phase, experimental testing will be conducted of technical solutions for a CBDC until summer 2023. The objectives and consequences of introducing a CBDC will also be analysed further, including the implications for monetary policy and liquidity management. This work will provide a basis for deciding whether Norges Bank will test a preferred solution.

The purpose of technical testing is to shed additional light on how solutions can deliver the necessary characteristics of a CBDC, and to uncover potential unintended consequences. Testing can also reveal economic and regulatory issues that are not captured by previous analytical work. The underlying technology for a CBDC is yet to be decided.

Norges Bank will draw on external providers in this work. The Bank has signed an agreement with a Norwegian company to program a simple prototype for issuance and destruction of CBDC tokens (see Section 2 for an explanation of terms). The Bank is also conducting tests in “sandboxes” for CBDC solutions from different providers. Furthermore, Norges Bank is in discussions with several Norwegian banks and payment service providers to test how a CBDC can be a means of payment in existing payment services.

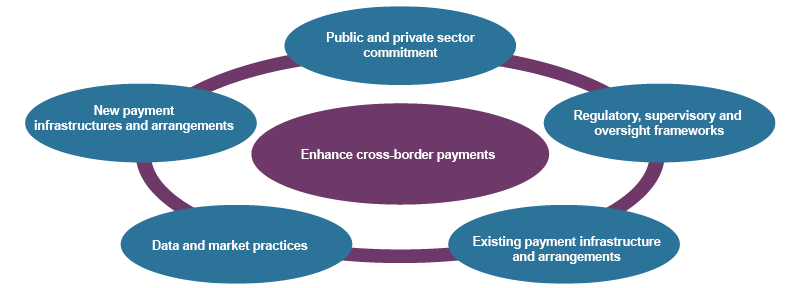

In this work, Norges Bank will seek to draw on experience from CBDC testing and other work conducted by other central banks and international organisations. International cooperation can also provide the basis for standardisation and system interoperability. In the G20 initiative for enhancing cross-border payments, one of the topics is interoperability between CBDCs for cross-border payments (see discussion in Section 4.3).

If the public in one country has access to a CBDC in another, financial and economic conditions could be affected in both countries, particularly if there is uncertainty about the financial position of the banking sector in the first country. It is therefore important to include potential cross-border effects when assessing a CBDC in Norway and the possible impact in Norway if CBDCs are introduced in other advanced economies.

4 Payment infrastructure

The payment infrastructure is the foundation of the payment system. Its function is to facilitate safe and efficient payments and payment settlement. Future-orientated changes to the infrastructure must be considered with a view to maintaining its safe and efficient functioning. Projects to assess a future real-time payment infrastructure and the introduction of the ISO 20022 messaging standard in the Norwegian payment infrastructure are underway. Work is also in progress internationally to improve cross-border payment systems.

4.1 Further development of the real-time payment infrastructure

Norges Bank has explored an expansion of its role as settlement bank to include the settlement of real-time payments. The primary objective is to facilitate the development of new real-time payment services for customers. The Bank’s assessment so far is that participation in the Eurosystem’s TIPS solution will promote the best development of Norwegian real-time payments in the years ahead.

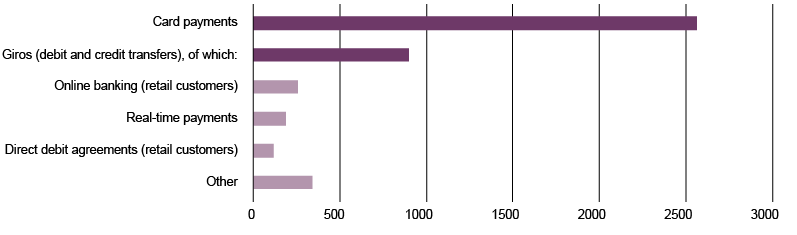

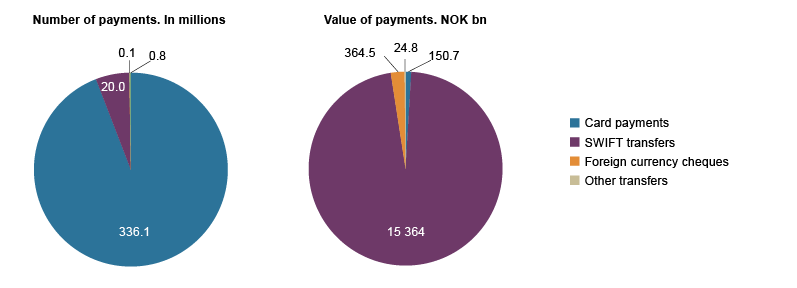

Real-time payments are payments where the funds are made available on the payee’s account seconds after payment is initiated – 24 hours a day and all year round. Today, bank customers can initiate such payments via online banking or the Vipps mobile payment solution. In 2021, 186m real-time payments were made in Norway (Chart 4.1).

Chart 4.1 Number of transactions in 2021 by payment type In millions

Norwegian banks have so far pursued a growth strategy and a high level of investment for Vipps. As a retail payment service, Vipps utilises several underlying layers of infrastructure in order to execute a real-time payment (Chart 4.2). The banks established an improved solution for real-time payments in the underlying infrastructure in 2020 through their common NICS interbank system (called NICS Real).43 The system provides for the receipt, exchange and clearing of interbank transactions. The net positions between banks when real-time payments are executed are settled at fixed times in Norges Bank’s settlement system (see box: The real-time payment process).

Chart 4.2 Simplified illustration of the layers in the real-time payment infrastructure44

The real-time payment process

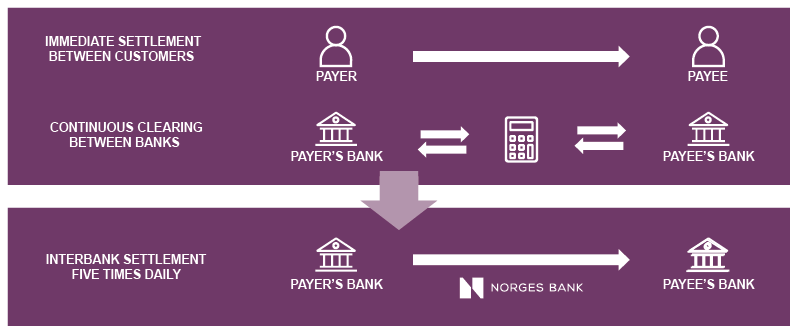

In a real-time payment, the funds are available in the payee’s account seconds after payment is initiated. As bank customers make real-time payments, NICS Real calculates how much a bank owes or is owed by another bank. A net position between banks is settled in central bank money at Norges Bank five times a day every weekday (Chart 4.3).

The credit risk that arises between banks because the settlement in central bank money takes place after the payment is made is virtually eliminated as each bank has set aside liquidity in a designated account at Norges Bank. This ensures that the banks can cover their payment obligations as soon as customers make real-time payments.

Chart 4.3 Real-time payment process in Norway

Need for further development

Most real-time payments in Norway are peer-to-peer (P2P) payments. Real-time payments can also offer social benefits in other types of payment situations and should therefore be developed in pace with the increasing demands and needs of different customer groups. In Norges Bank’s view, banks and other market participants should develop and offer new real-time payment services for businesses and the public sector. The use of real-time payments may become widespread in shops and for other payments that are currently made using payment cards. Most payments today are made using payment cards (Chart 4.1).

Expanded role for Norges Bank?

Banks have different needs, priorities and strategies related to ICT projects ahead and differing views as to the urgency of establishing new real-time services.45 In addition, payment services have become a competitive arena, among banks as well as between banks and other operators. This may weaken the incentive to develop a common underlying infrastructure.

In Norges Bank’s view, the extent to which banks – by changing, adapting and developing their own systems and solutions – will make use of the possibilities provided by NICS Real is uncertain. Norges Bank is therefore considering expanding its role in real-time payments. This would mean establishing a new system for real-time payment settlement operated by Norges Bank that would partially or fully replace the functions performed by NICS Real today. The system could also be designed for immediate settlement of real-time payments in central bank money 24 hours a day.

The Bank’s assessment so far is that participation in the Eurosystem’s TARGET Instant Payment Settlement (TIPS) solution will contribute to ensuring the best development of Norwegian real-time payments. Participation in TIPS means that interbank settlement of NOK real-time payments takes place in the TIPS system on behalf of Norges Bank.46

Participation in TIPS and the associated collaboration with other European central banks will ensure that the infrastructure for settlement of Norwegian real-time payments is developed in alignment with developments in the rest of Europe (see also boxes: Sweden and Denmark to use the ECB’s settlement systems and Further development of TIPS).

NICS Real and TIPS are both technically and functionally safe, efficient and modern underlying infrastructures for retail payment solutions. Both systems can provide payment exchange using the international messaging standard ISO 20022 (for more details, see Section 4.2). This provides a good basis for the development of new and efficient retail services and use of future global innovations in real-time payments. However, in Norges Bank’s view, by participating in TIPS – rather than banks continuing to develop NICS Real – Norges Bank will be in a better position to influence developments.

As system owner, Norges Bank will be able to take a coordinating and unifying role in getting banks to use the existing and future functionalities offered by TIPS. At the same time, developing retail real-time payment services will remain the domain of banks and other operators. For example, establishing real-time payment solutions for the corporate market may require adaptations and further development by businesses and their financial system providers. It is nonetheless Norges Bank’s view that the use of common standards and the predictability provided by participation in TIPS may stimulate banks and other operators to provide real-time retail payment services.

Norges Bank also considers that participation in TIPS and the establishment of efficient, forward-looking real-time retail payment services may reduce the risk of international operators establishing payment solutions based on alternative means of payment or dominating the market to such an extent as to impair Norwegian authorities’ management and control of important components of the payment system.

Sweden and Denmark to use the ECB’s settlement systems

Sveriges Riksbank concluded an agreement with the ECB in April 2020 on settlement of real-time payments in SEK using TIPS. The Riksbank has also announced that it aims to join the ECB’s other settlement systems TARGET2 and TARGET2-Securities later. In December 2020, Danmarks Nationalbank announced its decision to move all DKK settlements to the ECB’s systems in 2024/2025. This will include joining TIPS.

TIPS became operational in 2018 and has so far been in limited use. However, when Denmark and Sweden join the system, use of the system is expected to increase considerably. In addition, the ECB intends TIPS to be the core of the payment system for real-time payments and has announced measures to increase the use of the system.

Further development of TIPS

The ECB has arranged for participating central banks to report national needs for the development of new functionalities and other adaptations. The implementation of system changes will be decided in collaboration between participating central banks and the ECB. The question of whether TIPS could support cross-border multi-currency real-time payments is being explored (see also Section 4.3 on cross-border payments). If the ECB decides to enable a cross-currency capability in TIPS and Norges Bank decides to join TIPS, the service will also be available for real-time payments between NOK and the other participating currencies. Banks can then develop retail services for such payments.

Formal dialogue with the ECB

Norges Bank launched a public consultation in 2021 to elicit the views of the Norwegian banking industry and other stakeholders on the development of an infrastructure for real-time payments and a potential participation in TIPS.47 The banks and banking groups that submitted a response to the consultation agree that Norges Bank should enter into a dialogue with the ECB about joining TIPS. Joining TIPS will require banks to make appropriate arrangements and set aside resources.

The dialogue with the ECB was formally initiated in January 2022. Norges Bank has begun to review and assess the TIPS solution at a detailed level, including the technical setup, security, contingency arrangements and costs. Work is also in progress on an overall plan for implementing the system. Norges Bank has established a reference group for dialogue with banks and other relevant stakeholders through the process aimed at providing the basis for a decision on participation in TIPS and a currency participation agreement with the ECB that meets Norges Bank’s requirements and other relevant stakeholders’ needs.

If Norges Bank decides not to join TIPS, the alternative is for banks to continue developing NICS Real, while developing their own system solutions in line with the possibilities offered by NICS Real. Measures must be taken to ensure that developments are in line with society’s needs and that the necessary national governance and control functions in an appropriate manner also in the future. Norges Bank’s view is that in this case, banks must achieve wider agreement than in recent years on the further development of the infrastructure.

43 Bits, which is the Norwegian banking and finance industry’s infrastructure company, is the system owner for NICS and is licenced by Norges Bank. NICS Real is built on a technical solution that is owned, operated and further developed by Mastercard.

44 Retail payment solutions: Currently: Vipps and online banking.

Bank’s proprietary systems: Banks have to adapt their own systems in order to utilise the common underlying infrastructure.

45 See Norges Bank (2021f).

46 The terms of participation for Norwegian banks will be determined by Norges Bank within the framework set by the ECB for using the system.

47 See Norges Bank (2021f).

4.2 Introduction of ISO 20022

The international messaging standard ISO 20022 is set to be the payment messaging standard in Norway. With ISO 20022, messages can contain more information and the information is structured in a way that facilitates more automated treatment of payments. Banks, Bits and Norges Bank are preparing to introduce ISO 20022.