Norway’s road to inflation targeting

Norway suffered from a deep recession with a systemic banking crisis in the early 1990s. The prevailing fixed exchange rate system at that time had procyclical properties. Norway changed its monetary policy regime to that of inflation targeting and flexible exchange rates around the turn of the millennium. When the financial crisis hit in 2008 and when oil prices fell in 2014, the exchange rate channel in both cases helped absorb the shock and cushion the effects on the Norwegian economy. It is an open question whether the fear of floating exchange rates could have been overcome at an earlier point of time. However, the experiences from the past two decades tell us better late than never.

Norway suffered from a deep recession with a systemic banking crisis in the early 1990s. The prevailing fixed exchange rate system at that time had procyclical properties. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the German reunification in the autumn of 1990 and the rebuilding of the East German Länder led to higher German interest rates. These higher interest rates put pressure upwards on the Norwegian interest rates and thus aggravated the Norwegian crisis.

Norway changed its monetary policy regime to that of inflation targeting and flexible exchange rates around the turn of the millennium. When the financial crisis hit in 2008 and when oil prices fell in 2014, we could meet this with lower interest rates instead of higher rates as we did in the early 1990s. In addition, the exchange rate channel in both cases helped absorb the shock and cushion the effects on the Norwegian economy.

What if? Counterfactual simulations.

To illustrate properties of the fixed and flexible exchange rate systems, we have made counterfactual analyses of four episodes. You can read more about these episodes here. What would have happened if inflation targeting and flexible exchange rates had been introduced already in the early or mid-1990s? And what if a fixed exchange rate regime was still in place in 2008 and 2014? We have used the macroeconomic models available in Norges Bank at the time to conduct the counterfactual simulations.

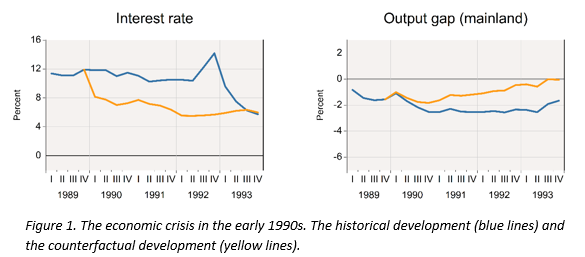

We made already in the late 1990s counterfactual simulations using the bank’s main macro model at that time, RIMINI, see figure 1. The results indicate how inflation targeting and flexible exchange rates might have dampened the recession in the early 1990s, allowing interest rates to be reduced during the prevailing deep recession.

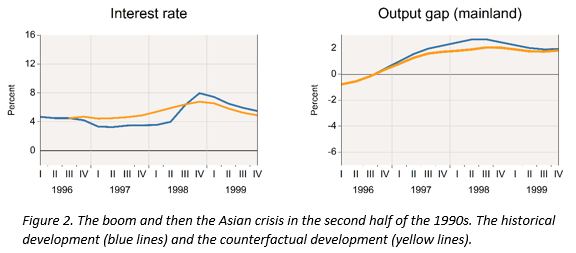

Together with Erling Motzfeldt Kravik and Yasin Mimir who work in the bank’s model unit, we have also applied the bank’s current main macro model, NEMO, to illustrate what would have happened if inflation targeting had been in place in the second half of the 1990s. Figure 2 indicates that that would have led to a smoother development than we experienced with the regime we had then.

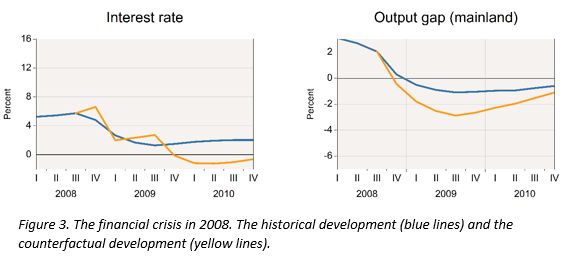

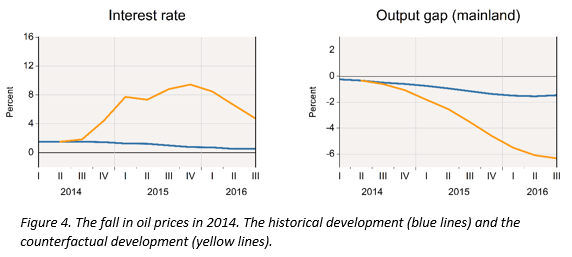

We have also used NEMO to conduct counterfactual analyses of two episodes in the 2000s, the global financial crisis in 2008 and the oil price fall in 2014, respectively. Both episodes took place after Norway had changed its monetary policy regime to inflation targeting and flexible exchange rates, and the counterfactual regime would then have been a return to fixed exchange rates.

The financial crisis hit us in 2008. Figure 3 shows that a return to the old fixed exchange rate regime would have incurred substantial output costs following a tightening of monetary policy in order to maintain a stable exchange rate.

In 2014 the oil prices fell significantly. The exchange rate functioned as a shock absorber. In a fixed exchange rate regime, we would have had to increase the interest rate significantly in order to defend the currency, causing a dramatic recession, twice in magnitude of the one we experienced in the early 1990s under the assumptions underlying this counterfactual scenario. However, as the shock in 2014 turned out to be a very persistent one, this would most likely have changed the policy response after some time, allowing for a devaluation of the nominal exchange rate. The illustrated counterfactual scenario is therefore not necessarily a realistic description of what would have been an optimal policy response in this situation under a fixed exchange rate regime.

Confidence and trust. That’s what matters.

It should be stressed that today’s monetary policy regime works because of its established credibility and confidence in the nominal anchor. It can indeed be questioned whether such credibility was in place as early as in 1990. The accommodating policy of the devaluation decade 1976-1986 had weakened the confidence among the public that monetary policy would deliver low and stable inflation. Thus, proposing a change in the monetary policy regime as early as in 1990 might have been interpreted as a reversion of the policy change four years earlier, and that the government, so to speak, was ”throwing the cards”.

Although New Zealand as the first country had introduced inflation targeting effective from February 1990, the inflation targeting regime was in its infancy, and was yet neither well known nor well established as an alternative monetary policy regime in Norway at the time. After all, there had been a considerable time for deliberations and for maturing the decision to move to inflation targeting in New Zealand, a process that started already in the early 1980s. Canada and Sweden followed suit and introduced inflation targeting as early as in 1991 and 1993 respectively, whereas it took another ten years before Norway introduced inflation targeting de jure in 2001.

We are not completely free to set interest rates even in a flexible exchange rate regime.

Monetary policy in a small open economy like Norway will always be constrained. The room for manoeuvre will be limited. For example, the combination of high oil prices and low international interest rates in 2010-2014 turned out to yield procyclical outcomes, notwithstanding the fact that Norges Bank used the freedom to maintain higher interest rates than in the Eurozone. But in times of crisis Norway has been well-served by exchange rate flexibility, which made monetary policy more countercyclical when needed, thus providing important relief which helped smooth the process adapting to the global financial crisis in 2008 and the drop in oil prices in 2014.

Fear of floating?

It is an open question whether the fear of floating exchange rates could have been overcome at an earlier point of time, such as in the midst of the 1990s. Then countries like New Zealand, Canada, Finland and Sweden had already pioneered adopting inflation targeting and floating exchange rates. However, the experiences from the past two decades tell us better late than never.

You find more about Norway’s road to inflation targeting and the counterfactual simulations here.

Bankplassen er en fagblogg av ansatte i Norges Bank. Synspunktene som uttrykkes her representerer forfatternes syn og kan ikke nødvendigvis tillegges Norges Bank. Har du spørsmål eller innspill, kontakt oss gjerne på bankplassen@norges-bank.no.

0 Kommentarer

Kommentarfeltet er stengt